Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 18

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected, according to calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of events that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to the structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1. Identification of systemic risks

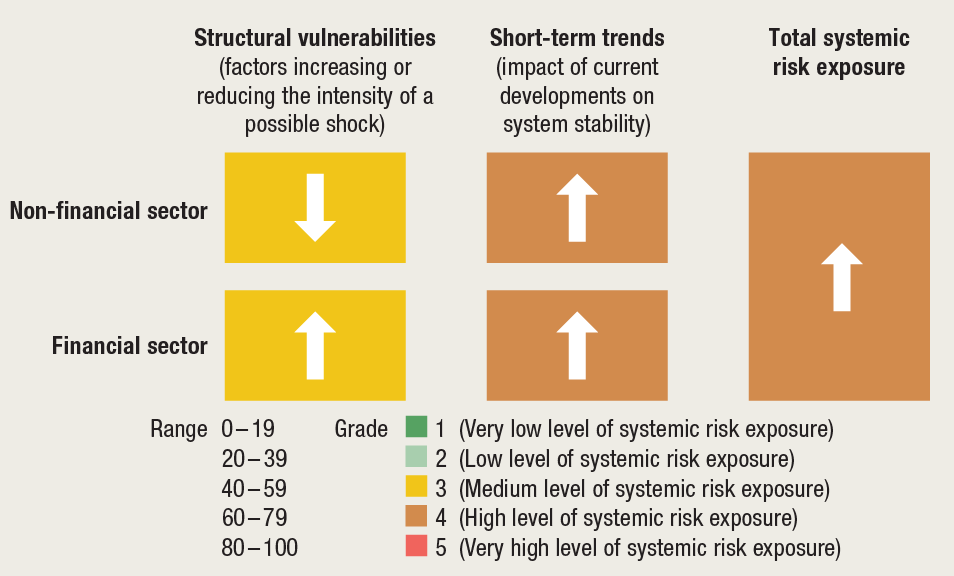

Despite favourable economic trends in the first half of 2022, the total exposure of the financial system to systemic risks towards the end of the year increased, driven by growing geopolitical uncertainties, scorching inflation and further monetary policy tightening (Figure 1). The fallout from the deteriorating geopolitical situation associated with the war in Ukraine is the main source of risk to Croatian economy. It has led to a reduced availability of energy products and materials. Coupled with the disruptions in supply chains, this has resulted in high inflation and growing uncertainty regarding economic activity. The anticipated further worsening of economic trends and the rise in the price of borrowing might lead to an increase in credit risk. The financial system resilience is backed by high liquidity, capitalisation and profitability, which might continue to grow next year following the increase in 2022. The resilience of the system will also be strengthened by the near elimination of currency risk following the introduction of the euro on 1 January 2023.

Figure 1 Risk map, third quarter of 2022

Note: The arrows indicate changes from the Risk map in the second quarter of 2022, published in Macroprudential Diagnostics No 17 (July 2022).

Source: CNB.

Coordinated tightening of monetary policies on a global scale continued to spill over to financial markets. The costs of government borrowing have been rising ever since the beginning of 2022 in most countries, with stronger effects in countries perceived as more risky or whose central banks have already started stronger monetary policy tightening. In parallel, interest rates on loans to the private sector have also risen. The US dollar has strengthened against most of the global currencies, reflecting safe investment with relatively high yields, which has further increased the debt burden of emerging markets that borrow in the US dollar. At the same time, a drop was recorded in the value of more risky financial assets, mostly in international capital markets, as a reflection of the rise in interest rates, uncertainties regarding macroeconomic and geopolitical trends and the unfavourable energy situation.

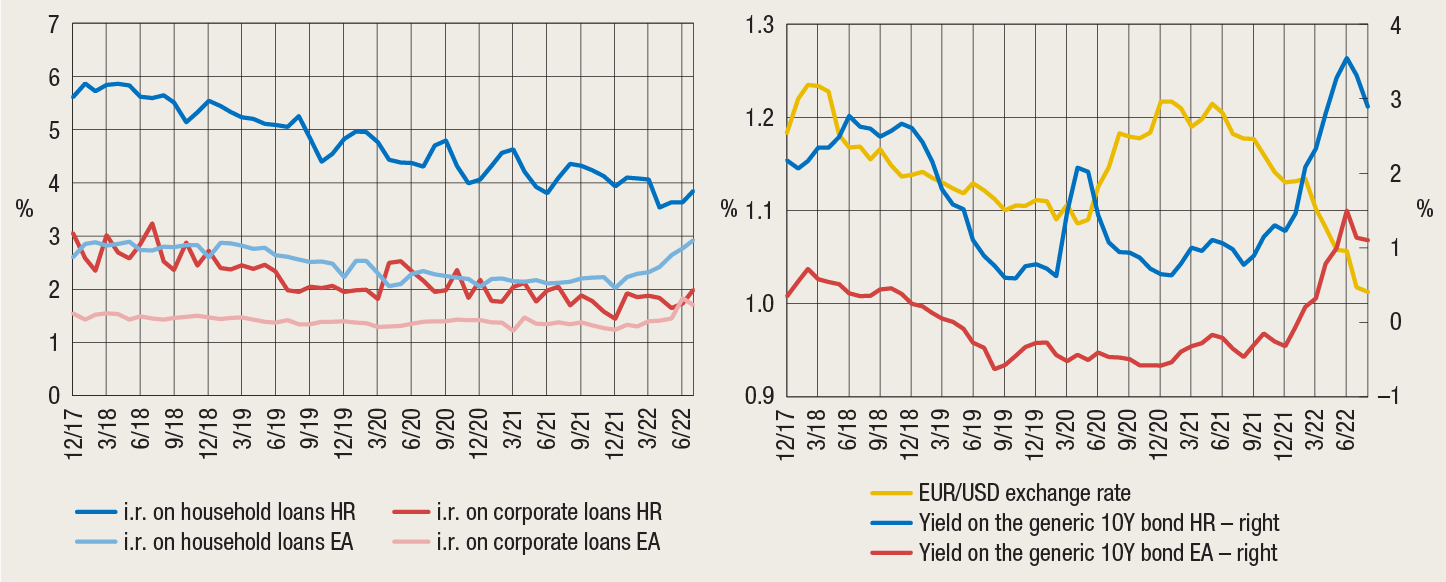

The spillover of tighter global financing conditions has had only a limited effect on Croatia so far. The absence of any significant effects in the financial market is mostly due to a reduced risk perception as a result of the envisaged introduction of the euro, the significant reduction in currency risk and the harmonisation of the CNB’s set of monetary policy instruments. The exchange rate of the kuna against the euro remained stable, while the increase in the yields on government debt was much more moderate than in the non-euro area CEE countries. Interest rates on household and corporate loans remained stable (Figure 2). Although the general government deficit is expected to decrease, the interventions aimed at alleviating the effects of the rise in energy prices, outside the scope of the state budget, pose risk to such favourable fiscal developments.

Figure 2 Trends in interest rates and bond yields in Croatia and the euro area

Sources: Bloomberg, ECB, Eurostat, CNB.

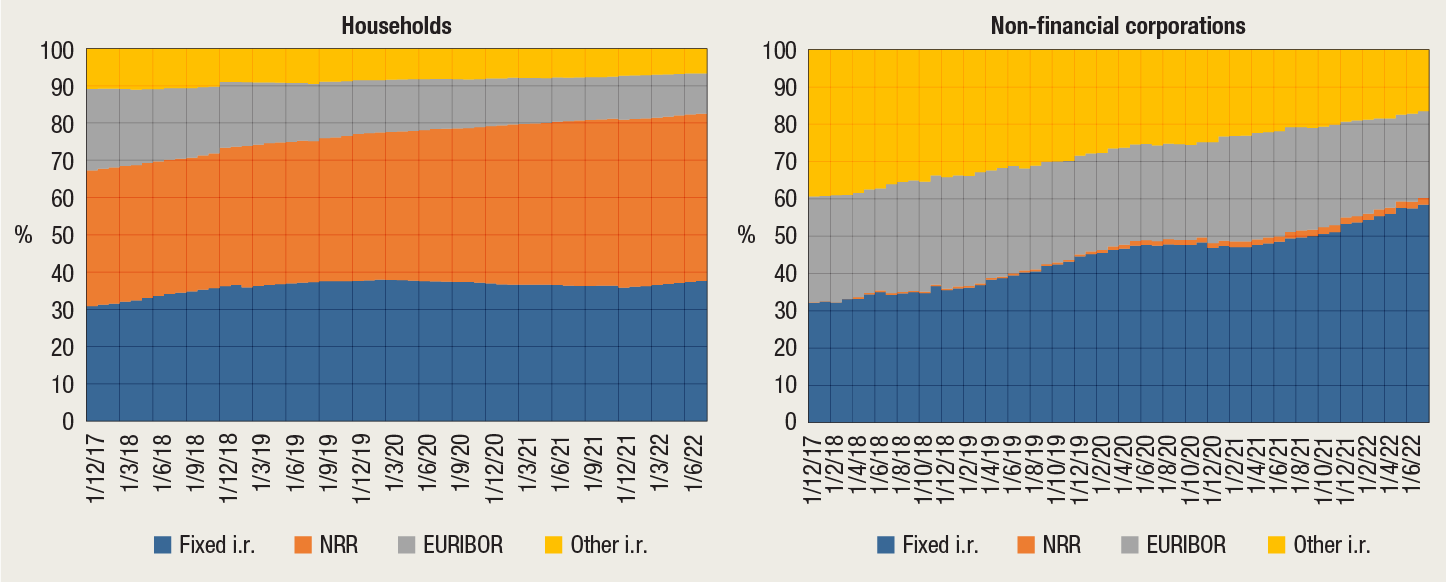

In the period of pronounced global geopolitical uncertainty and high and volatile energy prices, business confidence fell, with a strong rise in borrowing. Very good business results in 2021 and the first six months of 2022[1], associated with the good performance in tourism and strong demand, which facilitated offsetting the higher costs of corporate operations by an increase in the prices charged to clients, have had a favourable impact on the capital in the non-financial corporate sector. These factors have helped corporates to build up financial reserves for future periods, when the unfavourable impacts on their operations might materialise. In order to prepare for an uncertain future, corporates started borrowing more intensively, and the annual growth rate of corporate loans reached 16.7% at the end of August. Approximately one third of this growth is accounted for by corporate borrowing in the energy sector. At the same time, the rise in costs created the need to finance working capital, which corporates attempted to forestall by borrowing. In addition, the expected sharper tightening in credit standards and the uncertainty regarding price trends, the availability of inputs and demand also brought about an increase in precautionary borrowing in other activities. In the upcoming period, the unfavourable impact of the rise in the price of borrowing at the sector-wide level should be cushioned by a considerable share of loans with a fixed interest rate, standing at around 60% in this sector (Figure 3).

Although real incomes of households continued their downward trend, the growth in lending accelerated moderately, while the rise in EURIBOR, serving as a benchmark rate, exposed some borrowers to larger repayment costs. In the light of the persistently low bank financing costs, interest rates on existing household loans continued to decline in the first nine months of 2022, except interest rates on loans with a variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR, accounting for 11% of household loans (Figure 3). These loans recorded a monthly increase in interest rate in August 2022 (by 0.28 p.p. and 0.05 p.p. for cash and housing loans respectively). Combined with a fairly sharp rise in EURIBOR in the second half of this year, this will gradually expose these borrowers to larger repayment costs, even though over the short term they are protected by the legal restriction on the maximum permitted interest rates (see Box 1). Consumers can protect themselves from such risk by agreeing on temporary or permanent fixing of interest rate (see Information list with the offer of loans), with some banks offering this option in accordance with the CNB’s Recommendation from 2017[2]. Observing the household sector as a whole, the impact of the possible increase in interest rates on the debt servicing burden has, apart from the above legal restriction, also been considerably alleviated by the growing share of loans with a fixed rate (Figure 3), as well as those tied to NRR, which is slower to react to changes in financing conditions than EURIBOR.

Figure 3 Structure of loans by the variability of interest rates in Croatia

Source: CNB.

The activity and the prices in the housing market continued to grow, even though the likely increase in interest rates on housing loans increases the risk of a sudden drop in real estate prices. Following a boom of 13.5% on an annual level in the first quarter of 2022, real estate prices rose by 13.6% in the second quarter of 2022. Real estate purchases are largely financed by housing loans, which continued their upward trend at high rates (increasing by 7.3% in the first eight months of 2022), supported, among other things, by the still favourable financing conditions and the new spring round of the government housing loan subsidy programme, marked by a record high number of subsidised loans. Following a period of growth in the prices of construction materials, the prices stabilised in the second half of 2022, even though labour shortages in the construction industry persisted, exerting pressure on labour costs. High energy prices also contributed to the increase in construction costs. Despite these upward pressures on real estate prices, the uncertain economic trends, as well as tighter financing conditions, followed by potential exacerbation of the household debt servicing burden, increase the risk of a reversal of the current upward trend in the real estate market.

Although credit institutions remained well-capitalised and highly liquid and continued to increase their profitability, risks to their business operations in the upcoming period have been growing. Bank capitalisation considerably exceeded the minimum requirements, with total capital ratio standing at 25.0% in June 2022. However, the increase in yields on government bonds, accounting for approximately 9% of banking sector assets in late 2021 and early 2022, led to a decrease in their value, which had a direct impact on the fall in total capital ratio (by 0.6 percentage points in the first half of 2022)[3]. In addition, even though the share of non-performing loans fell to historic lows (3.8% at the end of June), the share of underperforming loans (stage 2 loans) increased, which might be an early sign of deterioration in the quality of the credit portfolio. In addition to one-off operating costs associated with the introduction of the euro, starting from next year, banks will also permanently lose most of their income from currency exchange, amid the possible rise in operating costs triggered by inflation. In contrast, despite the build-up of interest rate-induced credit risk, the rise in interest rates might also increase interest income and have a favourable effect on banks’ profitability.

Even though joining the euro area will considerably contribute to the decline in the exposure to systemic risks, it will also require reshaping of credit institutions’ business models. The introduction of the euro considerably reduces currency and currency-induced credit risk in the economy. Furthermore, the harmonisation of the set of monetary policy instruments within the scope of the adoption of the euro increases credit institutions’ liquidity surpluses, alleviating the pressure on the rise in interest rates. In addition to the elevated costs associated with the introduction of the euro, credit institutions’ operations could be hampered by a potential recession, putting additional pressure on their earnings.

Box 1 The extent to which borrowers with EURIBOR-linked loans are vulnerable to interest rate changes

This year’s increase in EURIBOR has had no influence on the trends in average interest rates on the existing household loans in Croatia so far, primarily owing to a considerable share of loans with a fixed interest rate and those tied to the NRR. However, the rise in EURIBOR might gradually affect the interest rates on loans with a variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR, which would affect the loan servicing costs, depending on the specificities of each loan, primarily on the remaining maturity. Although borrowers of loans with longer maturities are more exposed to interest rate risk, the legal restriction on the maximum permitted interest rate, which is lower on housing loans than other consumer loans, safeguards the borrowers over the short term, and the simulated effects of the increase in the repayment burden might materialise at a slower pace in the case of housing loans relative to other consumer loans.

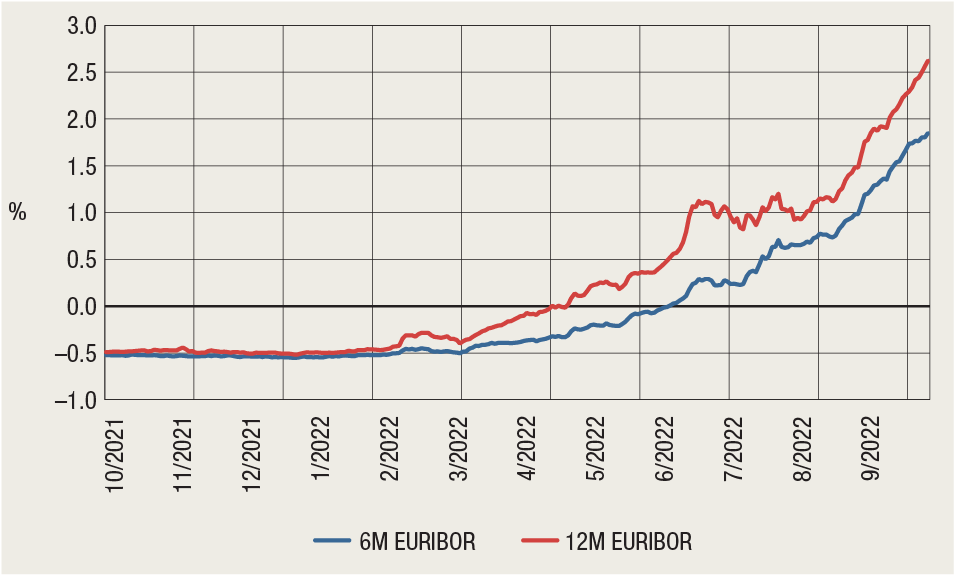

EURIBOR, representing interest rates with different maturities (up to 1 year) used in lending between the largest banks in the euro area, mostly reflects the expected trends in key interest rates set by the European Central Bank over the relevant horizon. Following a period of several years during which EURIBOR recorded negative values, it started to grow in 2022, picking up speed in the second half of the year. EURIBOR 6M[4], the most widely used benchmark interest rate for domestic household loans linked to EURIBOR (see Figure 3 in Chapter 1), increased by 2.39 percentage points (from –0.5% to 1.85%) from January to end-September this year. An even more robust growth was recorded in EURIBOR 12M, the variable benchmark which is not used as often. In the same period, it rose by 3.12 percentage points, reaching 2.63% at the end of September.

Figure 1 EURIBOR movements in the past year

Source: Bloomberg.

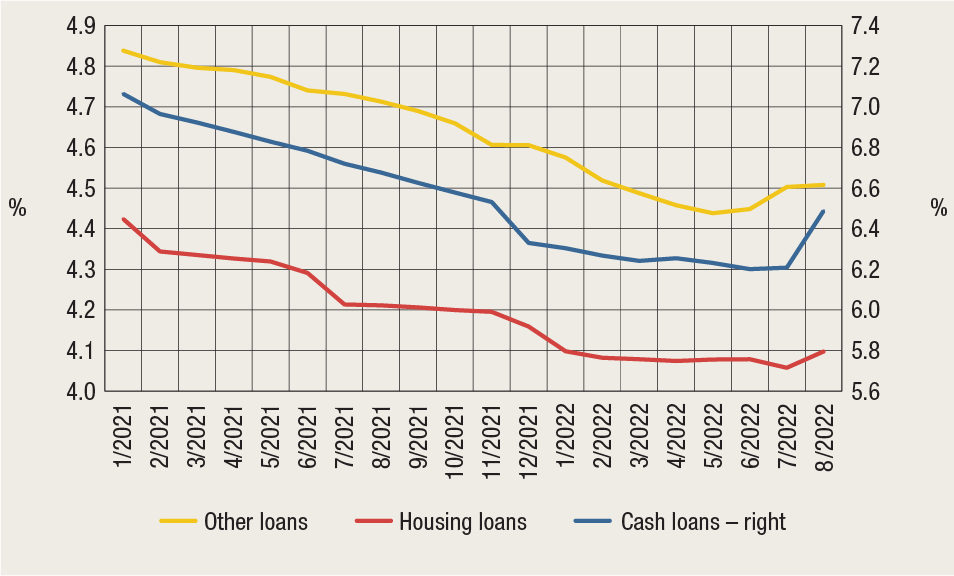

In view of the large share of loans with a fixed interest rate, as well as those linked to NRR, so far the aggregate data on interest rate trends have not shown any increase in interest rates on new or existing household loans. However, the average interest rate on loans with a variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR started picking up in August 2022, as a reflection of the movements in this parameter in the first half of the year (Figure 2). The average interest rate on general-purpose cash loans increased from 6.21% in July to 6.49% in August. On the other hand, interest rates on housing loans linked to EURIBOR increased only slightly.

The intensity with which the increase in EURIBOR will spill over to interest rates on housing loans is limited by legal provisions[5], according to which the maximum allowed interest rate on housing loans must not exceed the average weighted interest rate on the balances of such loans in a given currency (separately for HRK, EUR and CHF), augmented by one third. Most housing loans with a variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR are granted with an interest rate that is very close to and on the verge of the permitted maximum limit, making the further rise in interest rates on housing loans unlikely over the short term. The maximum allowed interest rate on other consumer loans must not exceed the average weighted interest rate on the balances of loans in a given currency (separately for HRK, EUR and CHF), augmented by a half. This means that the interest rate on non-housing loans might also increase in the short term.

Figure 2 Average interest rates on the balances of loans with a variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR

Source: CNB.

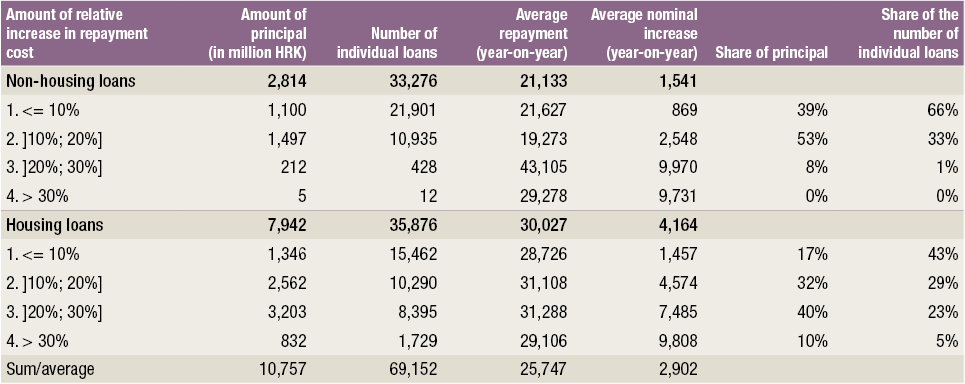

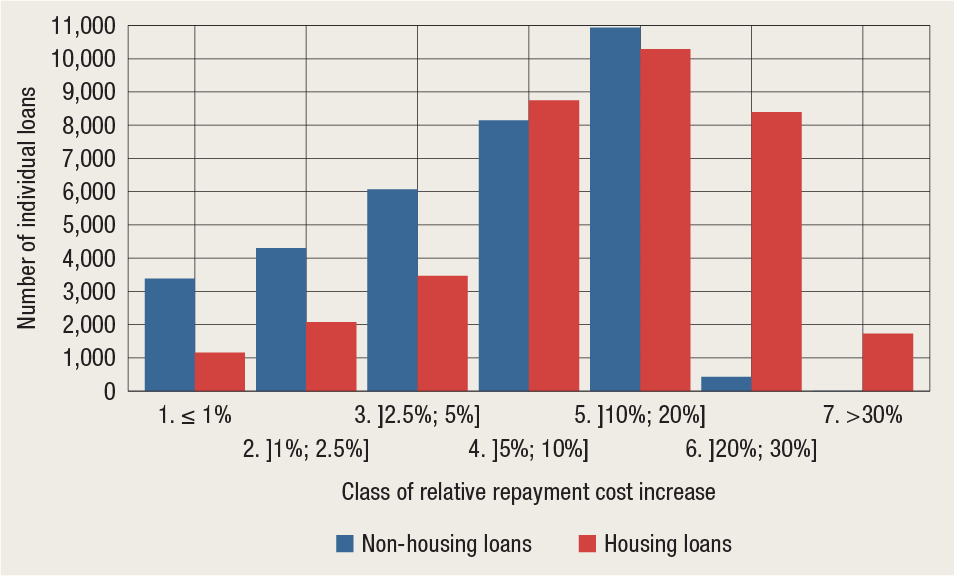

At the end of the previous year, approximately 76,500 consumers (7.2%) had around HRK 14.7bn worth of loans with interest rates linked to EURIBOR, constituting around 11% of the remaining principal of total household loans. Almost 42,000 consumers had housing loans with interest rates linked to EURIBOR, accounting for around 20% of the total number of natural persons holding a housing loan. If materialised in the period of several years, the further rise in interest rates on loans linked to EURIBOR might lead to a considerable increase in the repayment costs for some consumers. Table 1 and Figure 3 show the estimated growth in repayment costs for loans tied to EURIBOR in the event of a rise in interest rates on such loans by 3 percentage points. With regard to housing loans with a currently variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR, the cost of repayment of 28% of such loans (10,124 individual loans) would increase by more than 20% or HRK 7,882 on average on an annual level. Repayment costs would increase most for borrowers of loans with a long remaining maturity. Thus, the repayment cost for loans with the longest maturity (exceeding 20 years) would increase by more than 30% or HRK 9,808 on average. On the other hand, the rise in repayment costs would be considerably smaller for non-housing loans due to the shorter maturity. Only 440 individual loans (1%) would entail a rise in repayment costs of more than 20%, with such growth being less pronounced in most other loans.

Table 1 The effect of an interest rate increase of three percentage points on loans with EURIBOR-linked interest rate

Notes: The estimates refer to the portfolio of loans with a variable interest rate or interest rate that will become variable in 2022. Individual loans classified into the risk category “C” are excluded.

Source: CNB.

Figure 3 Number of individual loans according to the estimated effect of an interest rate increase of three percentage points on the relative rise in loan repayment cost

Notes: The estimates refer to the portfolio of loans with a variable interest rate or interest rate that will become variable in 2022. Individual loans classified into the risk category “C” are excluded.

Source: CNB.

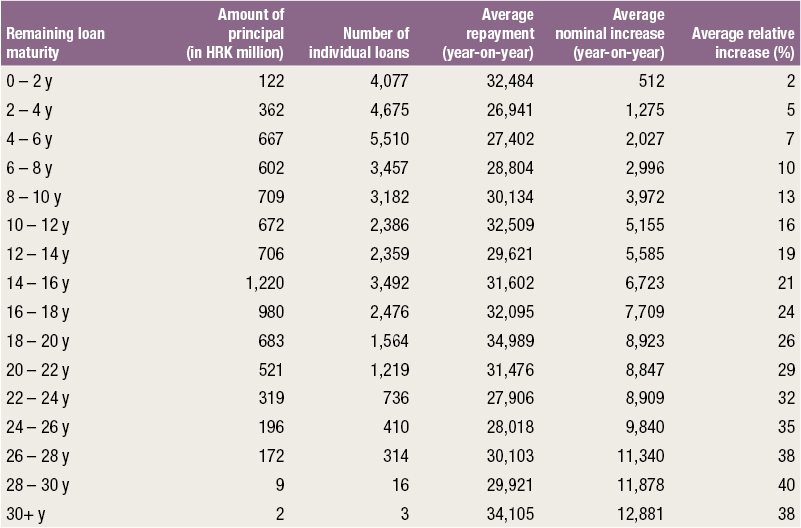

The impact of the rise in the benchmark parameter, or EURIBOR in this case, on loan instalments depends on the specificities of each loan, primarily on the remaining maturity. Table 2 provides an overview of the amount of principal, number of individual loans and the estimated nominal and relative increase in repayment costs in the case of an assumed rise in interest rates of three percentage points, relative to the remaining maturity of housing loans. The table illustrates that maturity is a key parameter influencing the interest rate risk for consumers, meaning that consumers holding loans with longer maturities can expect a higher relative increase in the repayment costs in the case of a hike in interest rates. In the case of a rise in interest rates of three percentage points, an instalment of a loan with a remaining maturity of 10 years would increase by approximately 13%, while that of a loan with remaining maturity of approximately 20 years would increase by a little over 26%. On average, in the portfolio of housing loans with a variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR, the relative repayment cost would increase by approximately 1.3 percentage points on average for every additional year of the remaining maturity.

Table 2 The effect of an interest rate increase of three percentage points on EURIBOR-linked housing loans depending on the remaining loan maturity

Notes: The estimates refer to the portfolio of housing loans with a variable interest rate or interest rate that will become variable in 2022. Individual loans classified into the risk category “C” are excluded. The mentioned classes of remaining loan maturity include the ceiling and exclude the floor.

Source: CNB.

The effect of the interest rate hike in the European market has only gradually spilled over to interest rates on loans in Croatia, curbed by the growth in average interest rates on loan balances. Such growth might accelerate in the case of a rise in interest rates on new loans or if banks start raising interest rates on deposits, which would be reflected in the movement of NRR. It is important to note that the effect of an increase in interest rates on loans linked to EURIBOR could be mitigated by decisions adopted by banks, with some banks offering the borrowers protection from interest rate risk by means of interest rate fixation. Consumers can also obtain information about the possibilities and conditions of protection from the increase in EURIBOR and other benchmark rates from their banks and other banks active on the market (see Information list with the offer of loans). The protection against interest rate risk is further facilitated by the fact that market interest rates are still at record low levels.

2. Potential risk materialisation triggers

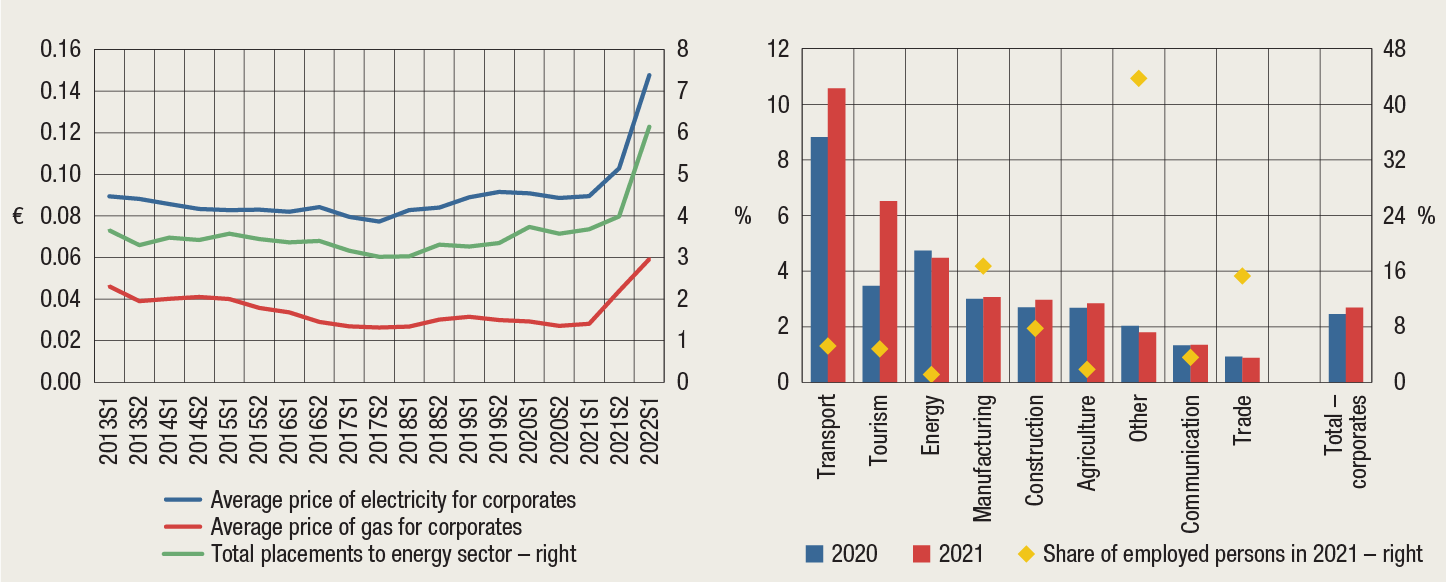

Protracted high costs of energy products, primarily of gas and electricity, might have a negative effect on the entire economy upon the expiry of government measures. Although Croatia’s dependence on the imports of energy products from Russia is slightly below the EU average[6], the rise in energy prices in 2022 has already affected corporate operations, mirrored in the increase in costs and liquidity pressures. However, amid ample demand, corporates have been able to offset the rise in operating costs by increasing the prices charged to their customers. The share of energy in the costs of corporates varies across activities, being the highest in activities associated with tourist services and transport, which witnessed the highest increase in these costs in 2021 (Figure 4). Persistently high prices of energy or any potential further increase would have a negative impact on corporate operations and the overall economic activity (Analytical annex 1).

Figure 4 Energy prices, borrowing of enterprises in the energy sector and the share of energy in the costs of corporates by activity

Sources: Eurostat, FINA and CNB.

Elevated inflation rates could bring about faster and sharper tightening of central banks’ monetary policies. The ECB raised its key interest rates by 50 and 70 basis points at the end of July and in mid-September respectively, while the Fed raised them by 75 basis points at the end of July and by 75 basis points at the end of September. There are still two meetings to be held by the end of the year, and it is expected that the ECB and the Fed might impose additional interest rate hikes. Against the backdrop of an increase in interest rates, there will be a growing pressure on the rise in the costs of new financing and loan servicing burden of borrowers not protected by fixed interest rates. Should high inflation rates linger for longer than currently expected, these negative effects will be even more pronounced. The spillover of tighter global financing conditions in Croatia has so far been evident from the rise in yields on government bonds, while a further spillover to the rise in interest rates on loans to the private sector, coupled with the increase in risk premium, might make debt servicing more difficult for some households and corporates. The tightening of financing conditions could also spur deflation of domestic and foreign demand for real estate. A significant rise in interest rates, reducing the attractiveness of investments in real estate, coupled with a drop in real income, might reduce market liquidity and also lead to a decrease in real estate prices at later stages.

In the light of rising uncertainty about short-term trends, the possibility of a recession cannot be fully eliminated. The ever-murkier economic outlook in the euro area, especially with regard to the German economy, which is highly sensitive to energy shocks, is the main contributor to a potential cross-border spillover of such negative trends in Europe, affecting Croatia as well. The potential recession would have adverse effects on budget revenues and reinforce pressures to increase certain budget expenditures. Amid recessionary conditions, real household income would probably continue its downward trend, adversely affecting the income of corporates as well and reducing their debt servicing capacity.

The potential further escalation of the energy crisis, a sharper tightening of monetary policy than currently expected and the probability of a recession are major threats to financial stability. The negative effects on the financial system would be mirrored in the lower quality of credit institutions’ portfolios due to reduced debt servicing capacities of households and corporates, and the decrease in the value of bonds and real estate kept by credit institutions as collateral. Each of the above factors and their concurrent occurrence might trigger the materialisation of adverse scenarios in the financial system.

Analytical annex: The effects of energy shocks on the operations of non-financial corporations in Croatia

The rise in energy prices led to a considerable increase in corporate operating expenses, further reinforced by indirect energy consumption through intermediate goods. However, according to the available indicators for corporations listed on the ZSE, in the first half of 2022 the corporations mostly managed to offset the rising expenses by increasing the prices charged to their customers. Still, the impact of disruptions in the energy market is uneven and particularly depends on the energy intensity of corporates, that is, of the activities in which they operate. In addition, the expected slowdown in economic growth will curb the possibility of offsetting such expenses in the future. Over the long term, it will be important to invest in technological improvements with the aim of reducing energy intensity and using energy more efficiently.

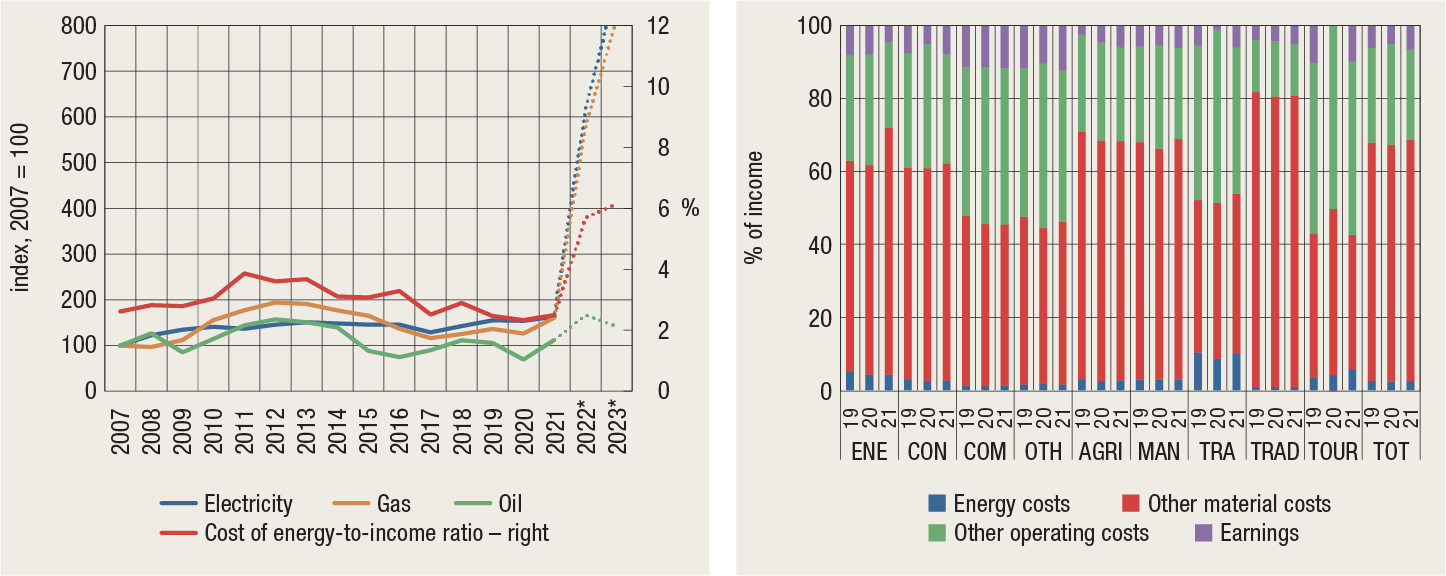

Hikes in energy prices are not unusual. However, the sharp increase recorded in 2022 is perceived as an unprecedented disruption by many corporations. Following their mild increase as early as in 2021, it is estimated that in 2022 the prices of oil, electricity and gas for corporates will increase by around 50%, 250% and 260% respectively. Oil prices are expected to drop by around 15% and electricity and gas prices are expected to rise by 40% in 2023 (Figure 1). Although some corporates have managed to protect themselves to a certain extent against such disruptions by entering into forward agreements (by linking the prices of products to the price of input), with the impact of increased prices moving forward, such financial techniques are usually employed by larger corporations, with larger volume of operations and a more advanced financial knowledge.

For non-financial corporations energy is an important input, involved directly and indirectly in a business process. The direct cost of energy in 2021 stood at around 2.5% of total corporate income on average (an increase from 2.3% in 2020). However, material costs, comprising energy costs to a certain extent, considerably exceed direct costs, accounting for up to 70% of corporate income[7] (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Trends in energy prices and energy cost-to-corporate income ratio in Croatia

Figure 2 Structure of corporate earnings[8]

Notes:* The projected trends in energy prices for 2022 and 2023 have been taken from the futures market (Bloomberg, end-September) and include prices without government intervention. The assumed growth in corporate income in 2022 and 2023 amounts to 30% and 15% respectively.

Sources: Eurostat and FINA.

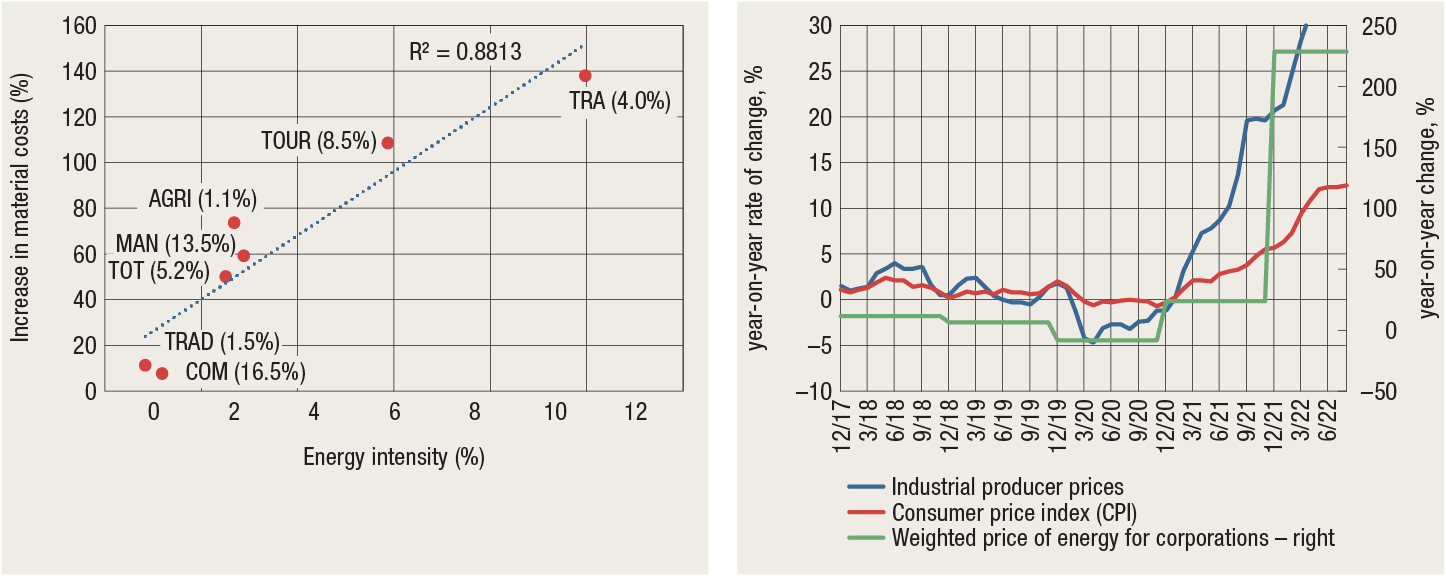

Pursuant to the data obtained from regular financial statements of corporations listed on the Zagreb Stock Exchange, material costs of corporations rose by around 50% in the first half of 2022. Although this is partly due to the increased volume of operations (income rose by around 42%, while total costs increased by around 34%), the intensity of the increase in costs was also propelled by the rise in energy prices. Even though corporate business performance improved at the aggregate level, this does not mean that corporations performed well in all activities. The greatest increase in material costs was recorded in the group of corporations that were most energy-intensive, i.e. those that were more reliant on energy in their operations. Transport and accommodation and food service activities are the most energy-intensive activities, and their material costs saw the largest annual increase in the first half of 2022 (Figure 3).

Corporations have been seeking to incorporate the increased input prices in the price of their products, as much as demand and competition allow. Albeit this possibility is limited, the trends in energy, producer and consumer prices in 2022 suggest a certain pass-through of the costs of energy to consumers (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Energy intensity and the increase in material costs in the first half of 2022

Figure 4 Trends in producer, consumer and energy prices for corporations in Croatia

Note: Energy intensity is the ratio between the cost of energy and corporate income. The number in parentheses shows the percentage of income in a given activity accounted for by corporations for which data are available from the ZSE for June 2021 and June 2022.

Note: The weighted price of energy for corporations is the weighted average of changes in the prices of electricity, gas and oil, under the assumption of an equal weight of 20% for oil and 40% for electricity and gas.

Sources: ZSE and FINA.

Sources: Eurostat and CNB.

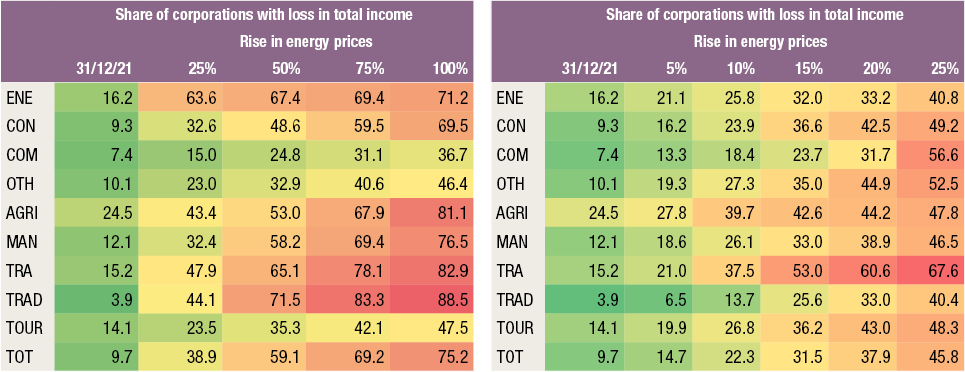

The rise in energy prices results in a direct increase in energy costs and consequently the total material costs of corporates and their marginal cost. According to a simple econometric model, a rise in energy costs by 1% would lead to an increase in other material costs of approximately 0.16%. Therefore, a rise in energy prices of 50%, very much the same as that seen in the first half of 2022, in the absence of any rise in corporate income and without necessary corporate adjustments, would result in the share of corporations with losses in sector income increasing from 10% to around 60% (Table 1).[9]

Energy shortage, which might occur in the upcoming periods, is a form of shock different from a rise in prices. In this analysis, it is observed only through the prism of a reduced volume of operations[10], even though in reality energy shortage would lead to both a rise in prices and a reduction in the volume of operations, which would have considerable adverse effects on corporates.[11] Under the assumption of the necessary proportionate reduction in goods/services and the impossibility of a sudden change in technology, a drop in available energy by 10% would lead to an increase in the share of corporations with losses in total sector income from around 10% to around 22%. In the case of a reduced availability of around 25%, the share of corporations with losses would stand at around 46%, with the highest share of around 68% accounted for by the transport activity, and the lowest share of around 40% accounted for by trade (Table 2).

Table 1 Effect of an energy price shock on performance of corporations

Table 2 Effect of an energy shortage shock on performance of corporations

Note: Activity abbreviations are explained in footnote 4.

Source: Author’s calculations based on FINA data.

Given that energy is mostly a variable input or a component of variable costs of corporations, an increase in its price leads to a rise in marginal cost and the formation of a new market price[12]. The above simulation comprises the estimated effect of the rise in the prices of intermediate goods on corporate costs, but not on corporate income. The results mirror the isolated effect of the rise in costs, without any compensating measures, and should thus be regarded as a very conservative estimate.

In reality, corporations have a certain degree of flexibility in their business processes and seek to adjust their operations in order to buffer the effect of high energy prices on profitability. Over a business year, corporations can replace more expensive energy sources or inputs with cheaper alternatives or attempt to set off the rise in prices by increasing the price of their products, depending on the characteristics of supply (market power) and demand (elasticity of demand). The absence of any significant adverse effects of this year’s energy shock on the business performance of non-financial corporations may be attributed to the ability to offset higher costs by raising the prices of products, against the backdrop of strong demand.

However, should energy prices remain elevated for a fairly long period of time, the expected slowdown in demand, amid the growing financing costs, could have an unfavourable impact on their ability to offset the increase in costs by increasing their revenues. This could lead to difficulties in the operations of some corporations, a decrease in the volume of production and a decline in employment and investment in fixed assets, which would have an unfavourable impact on the overall economic trends and intensify pressures for additional fiscal support, i.e. passing on a part of energy costs from energy consumers and/or producers to taxpayers.

Reducing energy intensity and transferring to safer, more stable and more environmentally friendly energy sources necessitate a change in technology and more time. Thus, a reduction in energy intensity and consequently of sensitivity to changes in energy prices, depends not only on the nature of operations, but also on the technical efficiency of corporations within a given activity. Over the long term, corporations could invest in the modernisation of technological processes with the aim of increasing energy efficiency, achieving a more rational energy management while still using the existing equipment and in the buildings and transferring to renewable energy sources, thus reducing sensitivity to energy shocks and building up significant savings. In that respect, the experience from the current energy crisis could provide opportunity for learning and supporting green transition.

3. Recent macroprudential activities

In the third quarter of 2022, against the backdrop of favourable macroeconomic trends and the continued upward phase of the financial cycle, accompanied by a high degree of uncertainty caused by the war in Ukraine and a worsened outlook for growth in the upcoming year, the CNB made no changes with regard to macroprudential policy measures. Following the regular quarterly assessment of cyclical risks, the announced countercyclical capital buffer rate remained at 0.5%, despite the build-up in these risks. However, if the economic trends remain relatively favourable, further build-up of cyclical risks would call for strengthening the resilience of banks by raising this rate in the upcoming period. The regular annual assessment of appropriateness of risk weight for real estate-secured exposures has found that the prescribed stricter risk weights remain appropriate in the light of risks stemming from banks’ exposure to residential and commercial real estate markets.

3.1 The announced countercyclical capital buffer rate will remain at 0.5%

The upward phase of the financial cycle continued amid high uncertainty regarding the geopolitical situation, which is why the announced countercyclical capital buffer rate remained at 0.5%. However, if cyclical risks continue to build up, even amid relatively favourable expectations regarding economic growth, the announced rate might be increased in the upcoming period. The regular assessment of cyclical systemic risks in the first seven months of 2022 has shown a continued build-up in these risks, mostly associated with the accelerated growth in housing prices and faster bank lending, particularly in the financing of non-financial corporations seen in recent months. Notwithstanding the foregoing, as the current geopolitical trends call for increased caution, the CNB decided that the announced buffer rate of 0.5%, applicable as of 31 March 2023, will continue to apply in the period after 30 September 2023 as well. However, if the economic and financial conditions do not deteriorate much in the coming months, in the next assessment cycle the continued build-up in cyclical risks could lead to an increase in the announced countercyclical capital buffer rate above the current level.

The CNB’s regular annual analysis has shown that the stricter[13]risk weights for real estate-secured exposures applied in the Republic of Croatia are still appropriate. This concerns the preferential risk weight of 35% which credit institutions may apply to exposures secured by mortgages on residential property only with a more restrictive definition of residential property than the definition laid down in the harmonised EU legislation, and the higher risk weight (100% instead of 50%) for exposures secured by mortgages on commercial immovable property. In its capacity as the designated authority, the CNB assesses their appropriateness at least annually, based on data on incurred losses and the estimate of expected losses on these exposures, taking into account risks associated with real estate market and a number of other relevant indicators in accordance with the EBA’s regulatory technical standards[14]. Should the assessment show that the prescribed ponders are inappropriate and do not reflect the actual risks associated with the exposures concerned, competent authorities may set higher risk weights or stricter criteria, on the basis of financial stability considerations. Having examined the incurred losses and the expected future potential losses on exposures secured by mortgages on residential property and commercial immovable property in the Republic of Croatia, it has been concluded that despite the elevated risks associated with the real estate market, a rise in losses that would require the adjustment of the currently applied weights is not expected in the upcoming period. Accordingly, the prescribed risk weights have been assessed as appropriate.

3.3 Actions taken at the recommendation of the European Systemic Risk BoardIn mid-September 2022, the CNB adopted the decision on the non-reciprocity of the macroprudential policy measure adopted by Germany, recommended for reciprocation by the ESRB[15], since the exposures of domestic credit institutions did not exceed the prescribed materiality threshold. In April 2022, the German federal financial supervisory authority adopted the measure[16] setting the systemic risk buffer rate of 2% for all exposures to legal and natural persons secured by residential property in Germany. The measure relates to all credit institutions authorised in Germany and will apply from 1 February 2023. As there are no credit institutions or direct exposures in the Republic of Croatia that would exceed the materiality threshold of EUR 10bn, using the de minimis principle, the CNB did not prescribe the reciprocation of the macroprudential measure adopted by the designated authority in Germany.

3.4 Implementation of macroprudential policy in other European Economic Area countriesFollowing a relatively sharp tightening of macroprudential measures in the first half of 2022[17], mostly triggered by the growing cyclical risks in the residential real estate markets, only a few EEA countries introduced or tightened these measures in the third quarter of 2022.

Bulgaria announced raising the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 2%, applicable as of the beginning of October 2023. The said increase continued the trend of the gradual raising of the rate with the aim of enhancing the resilience of Bulgarian credit institutions to a potential rise in non-performing loans and generally to difficulties in operations due to the deterioration of the economic situation. Lithuania announced bringing back the countercyclical capital buffer rate to its pre-pandemic level, raising it from the current 0% to 1% as of October 2023. The rate has been raised due to the accelerated increase in bank lending and property prices, and aims to strengthen the resilience of credit institutions, preparing them to the potential materialisation of risks in the future.

In addition to Lithuania, Belgium, Slovenia and Germany, Lichtenstein also introduced the sectoral systemic risk buffer for exposures secured by residential property. From May 2022, a 1% rate is applied for all exposures to natural persons that are secured by residential property and all exposures to legal entities secured by mortgages on commercial immovable property.

Slovenia introduced a more restrictive recommended loan-to value (LTV) ratio for borrowers not buying primary residential property, decreasing it from 80% to 70%, applicable from the beginning of July 2022. At the same time, due to the rise in the costs of living, banks were given greater flexibility in applying the exemption of 10% from the prescribed debt-service-to-income (DSTI) ratio. Thus, the exemption can also be applied if less than the 76% of income remains to borrowers after the payment of loan instalment.

Table 1 Overview of macroprudential measures applied by EEA countries and the United Kingdom

Notes: The listed measures are in line with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (CRR) and Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (CRD IV). The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication. Green indicates measures that have been added or changed since the last version of the table. Light red indicates measures that countries have released in response to the crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, which have not yet been reintroduced by 1 October 2022. Disclaimer: of which the CNB is aware.

Sources: ESRB, CNB and notifications from central banks and websites of central banks as at 1 October 2022.

For details, see:

https://www.esrb.europa.eu/national_policy/html/index.en.html and https://www.esrb.europa.eu/home/coronavirus/html/index.en.html.

Table 2 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

Note: The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication.

Source: CNB.

-

This relates to the enterprises listed on the ZSE. ↑

-

https://www.hnb.hr/documents/20182/2042017/ep26092017_preporuka.pdf ↑

-

Given that the majority of these instruments are kept in a portfolio valued through other comprehensive income. ↑

-

“6M” means the six-month EURIBOR and “12M” means the twelve-month EURIBOR. A total of around 55% of the principal of household loans with interest rates linked to EURIBOR (including those with periods of interest rate fixation) and around 80% of the principal of loans with a currently variable interest rate linked to EURIBOR are linked to EURIBOR 6M. ↑

-

See Consumer Credit Act (OG 75/09, 112/2012, 143/2013, 147/2013, 9/2015, 78/2015, 102/2015, 52/2016) and Act on Consumer Housing Loans (OG 101/2017). ↑

-

https://www.hnb.hr/en/analyses-and-publications/regular-publications/macroeconomic-developments-and-outlook ↑

-

The analysis includes corporations that reported the cost of energy in 2021 to FINA. This served to eliminate mostly micro and small enterprises. Consequently, the analysis included corporations accounting for 48% of all corporations, which (at the end of 2021) accounted for 92% of sector income, employing 87% employees. Data for 2022 have been obtained from the ZSE and refer to 71 corporations with available financial statements for June 2021 and June 2022. These corporations account for around 3.5% of sector income (according to FINA data). ↑

-

The following abbreviations are used in the analysis: ENE – Energy, CON – Construction, COM – Communication, OTH – Other, AGRI – Agriculture, MANU – Manufacturing, TRA – Transport, TRAD – Trade, TOUR – accommodation and food service activities. ↑

-

Operating income of corporations following an energy price shock is calculated by applying the following formula:

\(E B I T_{i j s}=S A_{i j 0}-O C_{i j 0}-\left(\left(\delta \mathrm{P} \times E C_{i j 0}\right)-\left(c_j+\delta \mathrm{P} \times \beta_j\right) \times O M C_{i j 0}\right)\)

where: i – corporation, j – activity, 0 – period preceding the shock, s – period of shock, EBIT – operating earnings, OC – operating costs, EC – energy cost, SA – income, OMC- other material costs, – change in energy prices, β – elasticity, and c – a constant value obtained by the regression analysis of the effect of the change in energy costs on other material costs. ↑

-

From the perspective of corporations, this shock is similar to non-compensated imposition of quota. ↑

-

Operating income of corporations in the case of energy shortage is calculated by applying the following formula:

\(E B I T_{i j s}=S A_{i j 0} \times\left(1-\mu_s\right)-\left(F C_{0 C}+V C_{i j 0} \times\left(1-\mu_s\right)\right)\)

where: i – corporation, j – activity, 0 – period preceding the shock, s – period of shock, EBIT – operating earnings, FC – fixed operating costs, VC – variable operating costs, SA – income, and – percentage of energy shortage. ↑

-

The application of a simple econometric model (Gu, L., Hackbarth, D., & Johnson, T. (2018). Inflexibility and stock returns. The Review of Financial Studies, 31(1), 278-321.) suggests that the share of fixed component of energy costs by activities ranges between 0.7% and 2.0%. ↑

-

Decision implementing the part of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 pertaining to the valuation of assets and off-balance sheet items and the calculation of own funds and capital requirements (OG 160/2011, 40/2015, 113/2016, 87/2018 and 53/2021, hereinafter referred to as: Decision) lays down stricter criteria for the application of the risk weight of 35% for exposures fully and completely secured by mortgages on residential property in the Republic of Croatia for the purposes of Article 125 of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013, through a more restrictive definition of residential property as set out in Article 14 of the Decision. Article 14a of the Decision concerned states that the risk weight for all the exposures fully and completely secured by mortgages on commercial immovable property in accordance with Article 126, paragraph (1) of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 will be increased from 50% to 100%. ↑

-

Regulatory technical standards specifying the types of factors to be considered for the assessment of the appropriateness of risk weights under Article 124 (4) of Regulation 575/2013 and the conditions to be taken into account for the assessment of the appropriateness of minimum LGD values under Article 164 (8) of Regulation 575/2013 ↑

-

Recommendation ESRB/2022/4 of 2 June 2022. ↑

-

Based on Article 133, paragraph (9) of Directive 2013/2016/EU. ↑

-

See Macroprudential Diagnostics No.17, July 2022. ↑