Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 20

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected, according to calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of events that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to the structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1. Identification of systemic risks

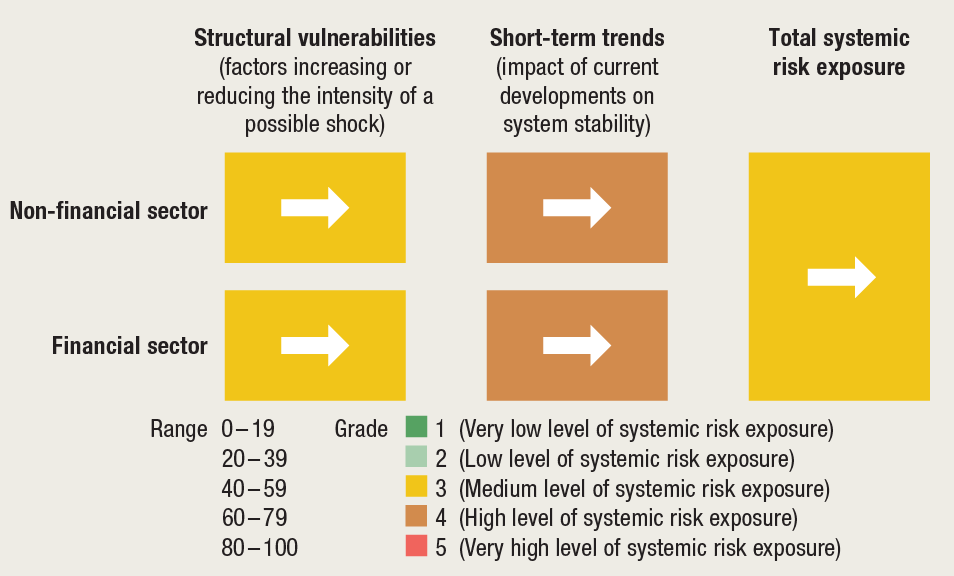

Risks to the financial system of the Republic of Croatia did not change significantly in the first half of 2023 and the exposure to systemic imbalances remained moderate with a somewhat more favourable outlook in the short term. The rise in interest rates and the tightening of lending conditions have increased the vulnerabilities of the non-financial sector and thus, against the backdrop of high inflation and economic slowdown in Croatia and the euro area, enhanced risks to financial stability. Still, the unfavourable effects of the economic slowdown, interest rate hikes and tightened financing conditions on households are mitigated by the still-strong labour market characterised by considerable growth in real wages. In addition, the solid performance of non-financial corporations in 2022 and the relatively moderate increase in the debt repayment burden support their resilience. Although prices of real estate continued to grow strongly in early 2023, market turnover slowed down noticeably, which, amid worsened financing conditions and weakened economic activity, suggests that the residential real estate market cycle might reverse.

Figure 1 Risk map, July 2023

Note: Arrows indicate changes from the Risk map published in Financial Stability No. 24 (May 2023).

Source: CNB.

At the turn of 2022 to 2023, the euro area economy entered a technical recession. Despite the decline in the prices of energy and the easing of supply chain bottlenecks, the outlook for industrial production in the euro area deteriorated further due to weaker domestic and foreign demand for goods and the first effects of tightened monetary policy on economic activity. On the other hand, the shift of demand towards services continued to support the activity of the service sector, which still performs relatively well following the subdued activity during the pandemic. At the same time, inflation in the euro area started to trend downwards, albeit slowly, and the path of its decline will depend on the speed of transmission of lower prices of raw materials and energy to the prices of food and the intensity of the pressure on prices in the service sector in the light of increasing labour costs.

The Croatian economy remained relatively robust in the first half of 2023 thanks to strong service activities, while growth in industrial activity remained subdued. Weak industrial production in Croatia may be linked to the slowdown in the exports of goods resulting from the slower economic activity of the main trading partners. On the other hand, the exceptionally good performance of tourism at the beginning of year and the available monthly indicators for the second quarter suggest that the strong demand for services is likely to continue. In line with the above, the CNB expects that the real rate of growth of the Croatian economy could reach 2.9% in 2023[1], a rate considerably above euro area average.

Inflation is showing signs of slowing down in Croatia, primarily under the influence of lower prices of energy and slower increases in the prices of food. However, core inflation slowed down only slightly. Among other things, persistent core inflation is driven by the strong demand for services, and the upcoming peak of the tourist season could spur further growth in the prices of some services. As a result of attempts to offset losses in purchasing power against the backdrop of a strong labour market paired with low unemployment and broad labour shortages, nominal wages picked up, enhancing inflationary pressures.

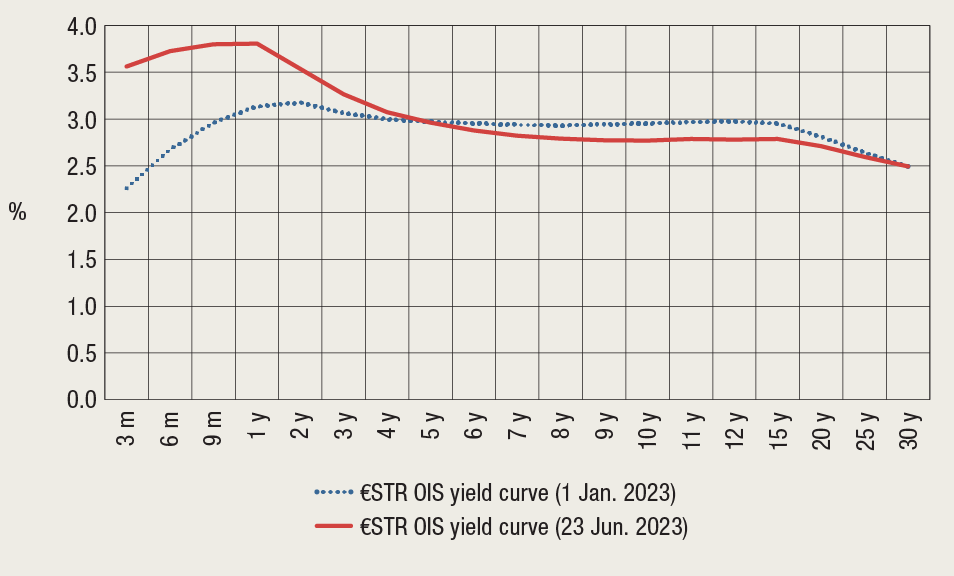

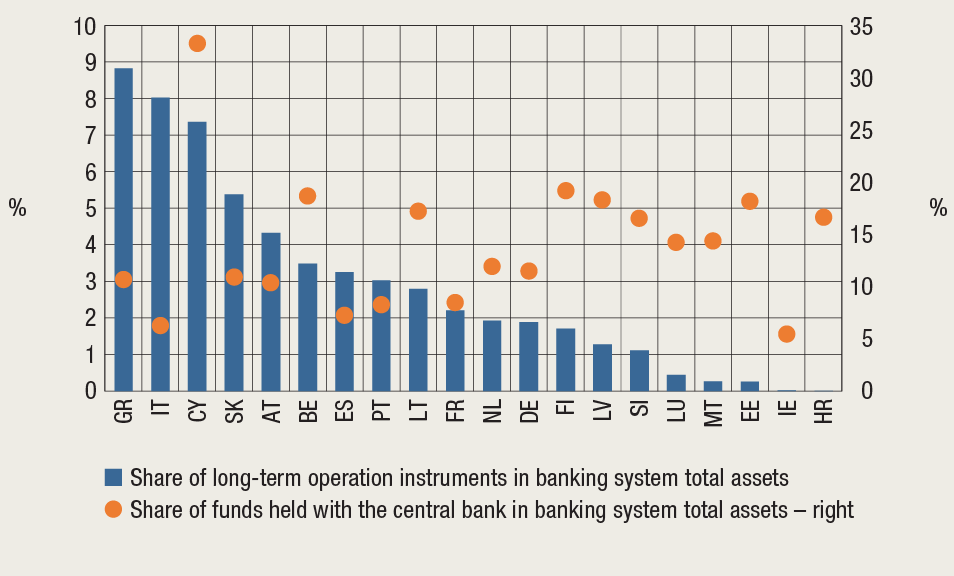

The persistence of core inflation signals the need for monetary policy to remain restrictive. In June, the European Central Bank further lifted key interest rates by 0.25 percentage points, thus having raised key interest rates by a total of 4 percentage points since the beginning of its monetary policy tightening cycle, over the course of one year. At the beginning of the year, financial markets anticipated that the ECB would raise key interest rates at a much slower pace. However, considering the persistence of inflation, the unfavourable outlook for inflation in the medium term and the time necessary for the transmission of the monetary policy measures taken up to that point, the Governing Council of the ECB opted for a faster pace of tightening. The tightening continued in March amid uncertainty regarding the condition of the US banking system and, to a lesser extent, the European banking system, following the failure of several large banks in the US and one bank in Switzerland. In the light of the aforementioned events, investors expected the ECB to delay or slow down the pace of its monetary policy tightening. Still, current market expectations suggest that the cycle of interest rate increases has not yet reached its end (Figure 2). In addition to interest rate increases, the end of reinvestment under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) and the increased maturing of loans extended under targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) further enhanced the restrictive character of monetary policy[2], which may increase risks of disorderly changes in market prices (Figure 3). Because Croatia became a member of the euro area in 2023, domestic banks were not able to participate in targeted longer-term refinancing operations and therefore have no outstanding liabilities arising from funds granted under the aforementioned programme.

Figure 2 Investors are expecting a higher ECB terminal rate after the June monetary policy decision than at the beginning of the year

Notes: Overnight index swap (OIS) rates refer to the rates agreed in interest rate swap contracts. The figure shows rates applicable to various maturities of OIS contracts based on short-term interest rates on the euro area overnight interbank market.

Source: Bloomberg.

Figure 3 Repayments under the targeted longer-term operations programme could have a strong effect on banking system liquidity in certain countries

Note: The data refer to April 2023.

Sources: ECB and CNB calculations.

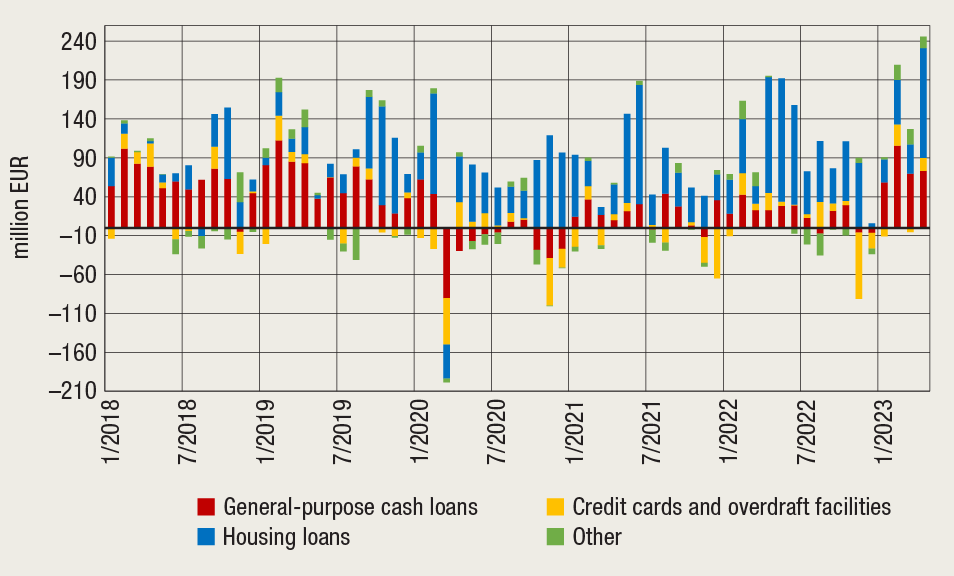

The growth in disposable income supports the resilience of the household sector. A strong labour market could continue to support the rise in disposable income and mitigate the effects of elevated inflation and growing interest rates on household vulnerability. Despite the increase in real wages, real consumption shrank in the first quarter of 2023, which may be motivated by households’ inclination to increase savings, which dropped to very low levels in 2022. However, monthly data on retail trade in April and May and the Consumer Confidence Survey point to recovered consumer optimism. The growth in cash loans to households picked up too: after standing at moderate levels for several consecutive years, the value of their transactions came close to the pre-pandemic period average early this year. Housing loans also continue to grow robustly, spurred by this year’s government housing loan subsidy programme cycle (Figure 4).

Interest rates on loans grew only moderately and for now, monetary policy tightening has not significantly increased the vulnerability of households. The resilience of households to the unfavourable effects of interest rate increase is supported by a significant share of loans made at a fixed interest rate and the broad use of the national reference rate (NRR) as the reference parameter for variable interest rates, which has increased only slightly thus far. Since the cap on the maximum interest rate on loans granted at a variable interest rate is also, in essence, significantly affected by the NRR, this supports the low level of restrictions for housing loans and has a stabilising effect on the materialisation of interest rate risk in housing loans. Finally, in the segment of loans linked to the EURIBOR, increased consumer activity aimed at mitigating interest rate risk has been noticed due to the rise in this parameter (see Box 1 Results of activities taken to inform consumers on interest rate risk). However, should monetary policy remain restrictive for a longer period, interest rates on deposits could grow, which could, in turn, affect the increase in the NRR and, consequently, the increase in the legal cap on variable interest rates.

Figure 4 Transactions of general-purpose cash loans reached levels recorded in early 2020

Source: CNB.

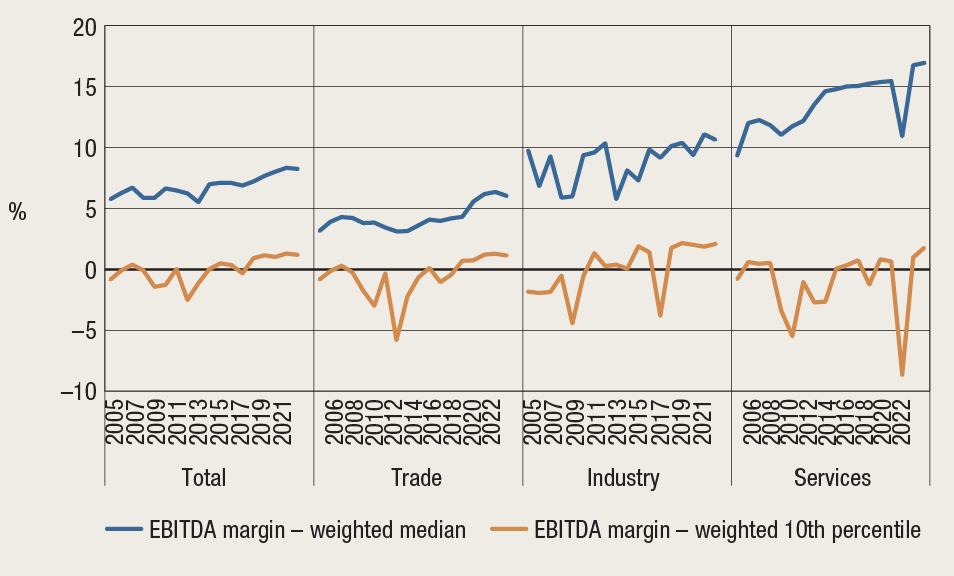

Figure 5 Distributions of profit margins point to satisfactory performance in 2022

Sources: FINA and CNB calculations.

Non-financial corporations experienced solid performance, with certain improvements observable in the segment of riskier corporations. In 2022, corporations managed to keep their profit margins on a high level and transfer the increase in production costs to consumers (Figure 5). Despite the asymmetrical influences of the sharp rise in the prices of energy and raw materials, riskier corporations improved their performance as well, with the greatest improvement in business performance seen in corporations engaged in tourism-related service activities, which were affected the most by the pandemic. Following the strong growth in lending in 2020, particularly to corporations in the energy sector under the influence of growing energy prices, the drop in the prices of energy and raw materials at the beginning of the current year reduced the demand for loans. Interest rates on newly-granted loans to non-financial corporations continued to grow in the first half of 2023, which started to affect corporate interest expenses. In addition, since the beginning of 2022, the share of long-term loans and loans granted at a variable interest rate in newly-granted loans has increased. This could increase the effect of interest rate risk on business activities of non-financial corporations. Still, good business performance, growth in liquidity and increase in capital relative to debt increase their ability to absorb higher financing costs (for more information see chapter C, Financial Stability No. 24).

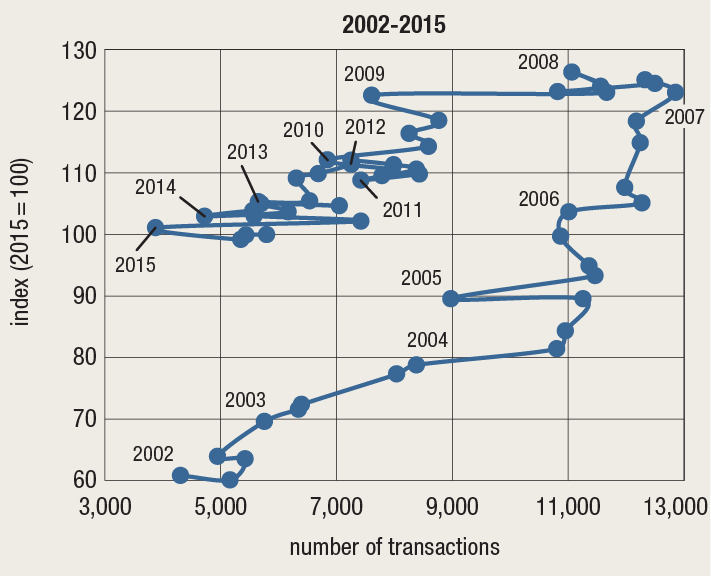

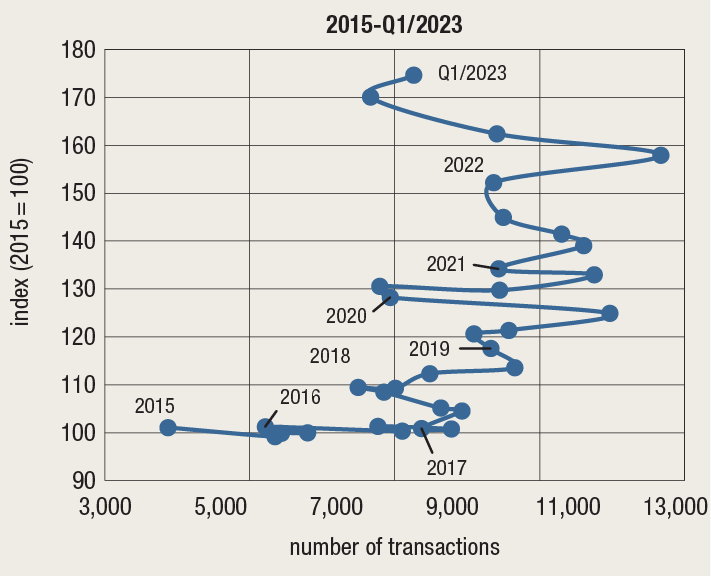

Although prices on the real estate market continue to grow strongly, the decrease in the number of transactions amid deteriorating financing conditions suggests that the cycle on the real estate market could reverse. According to CBS data, the rate of growth in residential real estate prices was 2% on a quarterly basis in the first quarter of 2023 and 14% relative to the same period in the year before. The developments on the real estate market in Croatia thus continue to diverge from the trends in other EU member states, where prices began to decline as early as in the second half of 2022. The number of transactions on the real estate market in Croatia began to decrease from mid-2022, pointing to weaker demand and signalling the possibility of a reversal of the current cycle on the real estate market (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The exposure of the banking sector to risks on the real estate markets remained at levels similar to those in 2022, with the decline in the loan-to-value ratio signalling a possible tightening of the conditions for granting new housing loans.

Figure 6 Real estate market cycle from 2002 to 2015

Note: The figure shows quarterly data, and labels assigned to individual observations refer to the beginning of the year.

Sources: CBS, Tax Administration and CNB calculations.

Figure 7 Real estate market cycle from 2015 onwards

Note: The figure shows quarterly data, and labels above data refer to the beginning of the year.

Sources: CBS, Tax Administration and CNB calculations.

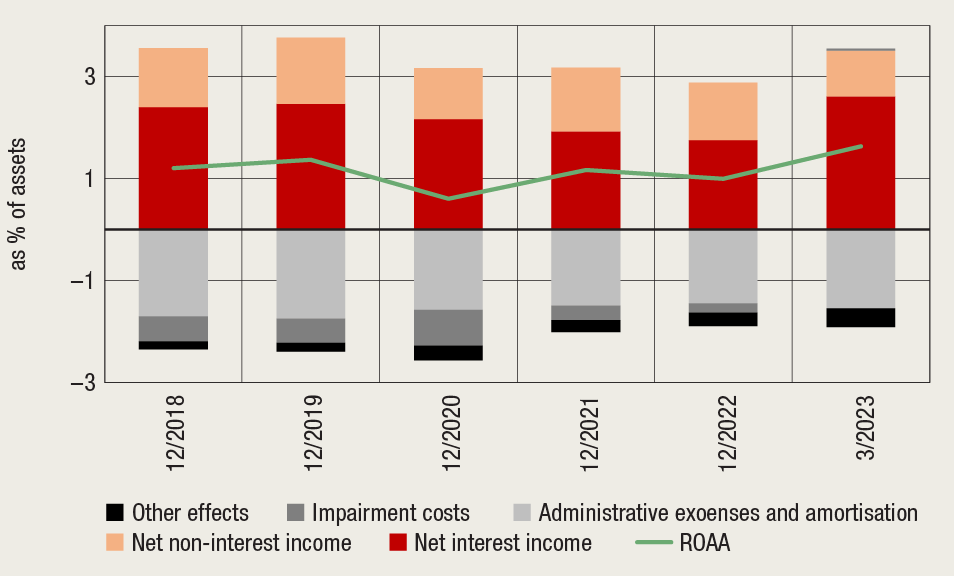

The banking system is highly liquid and capitalized, its resilience supported by the continuous growth in profitability. The total capital ratio of banks decreased from 24.8% at the end of 2022 to 23.6% at the end of the first quarter 2023 as a result of a distribution of profits from the previous year and the lower amount of transitional adjustments of common equity tier 1 capital[3], but nevertheless remained high, particularly compared to other euro area members. In the first half of 2023, the profits of banks increased sharply thanks to the rise in key interest rates and the fact that lending interest rates of banks reacted faster and more strongly to monetary policy tightening than deposit rates, increasing the banks’ net interest income (Figure 8). In this context, a significant amount of income comes from the use of the overnight deposit facility with the central bank. The low cost of banks’ funding sources results from deposits dominating the banks’ funding sources and the exceptionally high liquidity surpluses enabling banks to maintain the cost of attracting deposits at low levels. Although the outflow of transaction deposits in the first half of 2023 linked to the issue of a national bond slightly reduced stable funding sources, they still far exceed regulatory requirements.

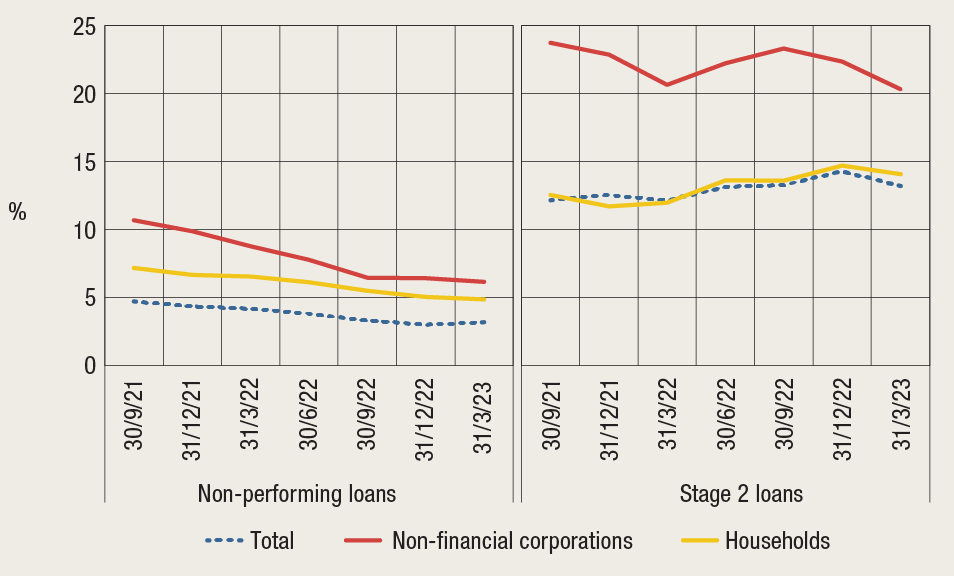

The quality of the banks’ loan portfolio is still favourable, and deterioration is only anticipated in case of a more noticeable worsening of macroeconomic conditions or stronger spillover of monetary policy tightening to financing conditions. Although the value of non-performing loans continued to decline, in the first quarter, the share of non-performing placements in total placements grew slightly (by 0.2 percentage points) on account of a faster decrease in total placements due to the drop in the amount of funds held with the central bank. Only the slight increase in stage 2 loans in the manufacturing industry and the energy sector might indicate a possible increase in credit risk.

Figure 8 As well as in interest rates, increase has been observed in net interest income of banks

Notes: Other effects include all other income statement items that do not affect profit after tax. Values for the first quarter of 2023 are annualised for the purpose of comparison with the previous years.

Source: CNB.

Figure 9 Share of non-performing loans in total bank loans continued to decline

Source: CNB.

Box 1 Results of activities taken to inform consumers about interest rate risk

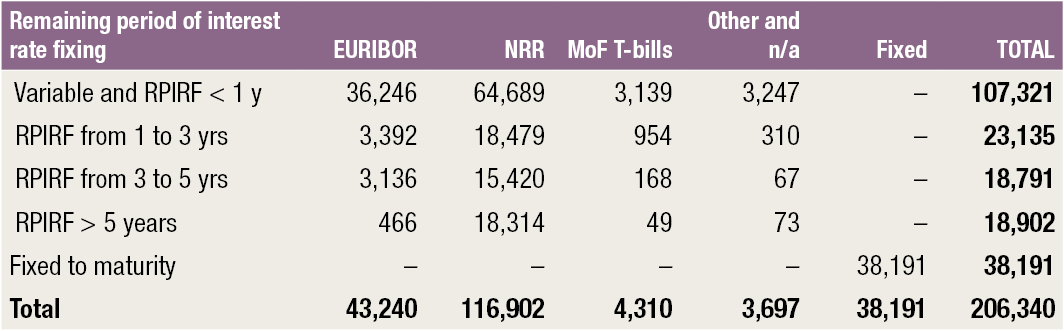

The rise in the ECB’s key interest rates and the increase in market rates raised the question of interest rate risk in consumer loans, particularly housing loans with long remaining maturities. Of some 206 thousand housing loans active in late 2021, prior to the beginning of the monetary policy tightening cycle, almost one half had a variable interest rate or a remaining period of interest rate fixing amounting to no more than one year (Table 1). Among these, roughly one third applied the EURIBOR, which responds quickly and strongly to changes in ECB’s key interest rates, as the reference parameter, and were therefore most exposed to interest rate risk.

Table 1 Structure of housing loans according to reference parameter and interest rate variability

Notes: RPIRF means “remaining period of initial interest rate fixing”. Loan accounts classified as risk category C as at 31 December 2021 have been excluded.

Source: CNB.

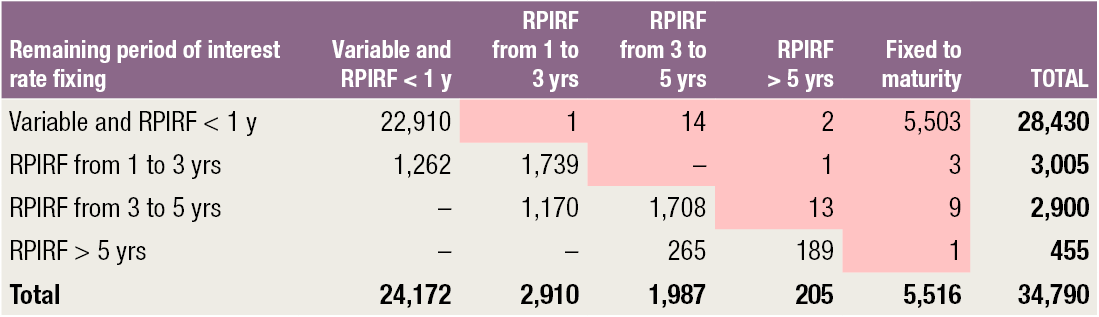

In 2022, some consumers and credit institutions recognised the interest rate risk that became noticeable with the significant increase in the EURIBOR. To hedge against a possible increase in loan repayment costs, in the same year, some consumers accepted the offers of banks to fix the interest rates on loans, or undertook their own activities to fix interest rates. In the course of 2022, consumers fixed interest rates for some 5,500 loans out of a total of 28,500 housing loans that were still being repaid at the end of 2022 and had a variable interest rate linked to the EURIBOR at the end of 2021 (Table 2). Furthermore, consumers fixed the interest rates of 350 additional loans linked to other reference parameters (95% of such loans were linked to the NRR), while for a further 130 such loans, the period of interest rate fixing was extended. Since the total population of such loans amounted to 57 thousand, it is evident that interest rates were fixed mainly by consumers with the EURIBOR as the reference parameter[4].

Interest rate fixing was, by and large, performed by consumers who had loans with relatively high interest rates. In addition to interest rate fixing, almost all consumers also negotiated a lower interest rate, so that the average interest rate on such loans went down from 4.25% in late 2021 to 3.44% in late 2022. Interest rates on loans which remained linked to the EURIBOR remained relatively stable, averaging 3.93% at the end of 2022, which is a result of the application of the legal cap on variable interest rates on housing loans[5]. For slightly less than 80% of such loans, the interest rate decreased, while for almost 20%, it went up. The average remaining maturity was similar for both groups of loans (those granted at a fixed interest rate and those granted at a variable interest rate with EURIBOR as the reference parameter), hovering around 13 years at the end of 2022.

Table 2 Migration of loans linked to the EURIBOR in 2022

Notes: Rows show the distribution of loans according to the RPIRF in 2021, while columns represent the distribution for 2022. The values in the table show the number of loan accounts that transitioned from one category of RPIRF to another in the course of 2022. The table shows only loan accounts active as at 31 December 2021 and 31 December 2022. ‘IR’ stands for interest rate. Shaded cells indicate loan accounts whose period of interest rate fixing was extended in the period between 31 December 2021 and 31 December 2022.

Source: CNB.

Interest rate risk for consumers is mitigated in the short term by the broad application of the NRR as the reference parameter and the legal interest rate ceiling applicable on housing loans with a variable interest rate. However, in the medium term, loans linked to the NRR will also be exposed to interest rate risk, as an increase in the NRR would raise the legal ceiling for variable interest rates and further enhance the interest rate risk for loans linked to the EURIBOR. The still-low level of deposit interest rates mitigates the risk of a more significant increase in the NRR in the short term. However, a rise in deposit interest rates has been apparent in the euro area since mid-2022, with the most prominent increase visible in interest rates on time deposits (which have, since then, increased by 1.5 p. p.). Similar developments, although somewhat more moderate, have been observed in Croatia as well, and, bearing in mind the likely persistence of the ECB’s restrictive monetary policy over a longer period, the trend may be expected to continue. The possible spillover of sight deposits to time deposits spurred by the increase in deposit interest rates could additionally strengthen the increase in banks’ financing costs and drive the NRR upwards. Since interest rates on loans linked to the NRR currently stand below the legally prescribed maximum, such a scenario could enable a relatively fast increase in repayment costs for debtors with loans granted at a variable interest rate linked to the NRR (see Financial Stability No. 24, Figure C.14). An increase in deposit interest rates would, at the same time, raise the legal interest rate ceiling applicable on loans with a variable interest rate and thus create additional room for growth in variable interest rates on existing housing loans.

2. Potential risk materialisation triggers

Due to the continued war in Ukraine and increasing global political antagonisms, the geopolitical situation remains an important risk materialisation trigger in the context of financial stability. Although the attention paid by financial markets to the conflict between Russia and NATO is diminishing (Figure 10), the possibility of a direct conflict keeps global geopolitical risks high. Recently, tensions between China and the USA increased significantly as well, and Chines military actions in the Far East, paired with the continued technological decoupling of China from Western countries, could additionally raise tensions in mutual relations.

Figure 10 Geopolitical risks remain strong

Notes: The BlackRock Geopolitical Risk Indicator (BGRI) tracks the relative frequency of brokerage reports (via the Refinitiv platform) and financial news (Dow Jones News) related to certain risks. In the formation of the indicator, greater weight is assigned to data from brokerage reports. The BGRI reflects the level of market attention for each risk in relation to the preceding five-year period.

Source: Black Rock Institute.

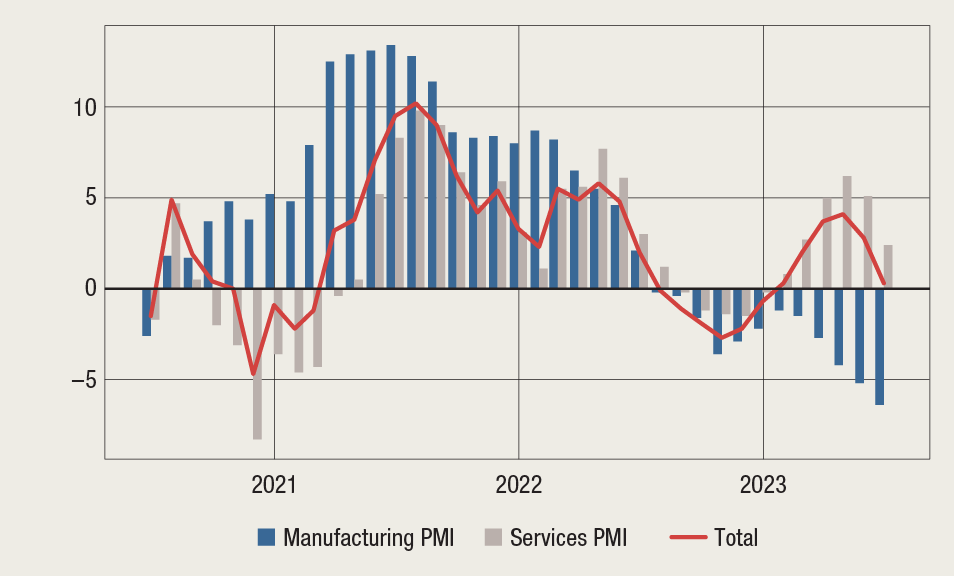

Figure 11 Slowdown in euro area economy

Note: The data shown were obtained by deducting the Purchasing Manager Index value from 50: positive values reflect periods of expansion, while negative values indicate periods of economic contraction.

Sources: Bloomberg and CNB calculations.

Unfavourable macroeconomic developments may enhance risks to financial stability, particularly if economic activity contracts more strongly. The most recent high-frequency indicators in the euro area suggest that real developments could continue to fall short of current projections, which anticipate a slight growth in 2023. In June, the composite PMI index fell to 50.3, in line with economic stagnation in the euro area, with a noticeable slowdown in the growth in the service sector and a further decline in the manufacturing industry signalling a possible strong deceleration of the economy (Figure 11). Unfavourable macroeconomic developments could undermine the capability of households and non-financial corporations to settle their credit obligations in an orderly manner, in turn negatively affecting banks and other financial institutions.

Persisting high inflation in the euro area could spur further monetary policy tightening. Upward pressure on prices could come from a renewed increase in the prices of raw materials, particularly energy, which could result from efforts to fill European gas storage facilities in parallel with the reopening of the Chinese economy. In addition, should wages grow more strongly than expected, and corporations continue to pass on their input costs to consumers and maintain high profitability, inflation could be higher than currently projected.

Continued increases in interest rates could, if coupled with strong economic contraction, lead to a disorderly drop in turnover and prices on the real estate market. Although in other euro area countries, the real estate market already began to slow down in late 2022, the decline in prices and number of transactions has thus far been small, without systemic effects. Although current developments suggest that similar trends are possible in Croatia, i.e., that a moderate drop in real estate prices could ensue after the decline in the number of transactions, the risk of more unfavourable outcomes cannot be excluded. A stronger deterioration in the domestic and external macroeconomic environment could, paired with weakening of the labour market, trigger a stronger-than-expected decrease in market liquidity and decline in real estate prices. Furthermore, additional stronger tightening of bank lending conditions could reduce access to lending and reinforce negative developments. In such an environment, credit risk would increase for banks, and collateral value and marketability would drop.

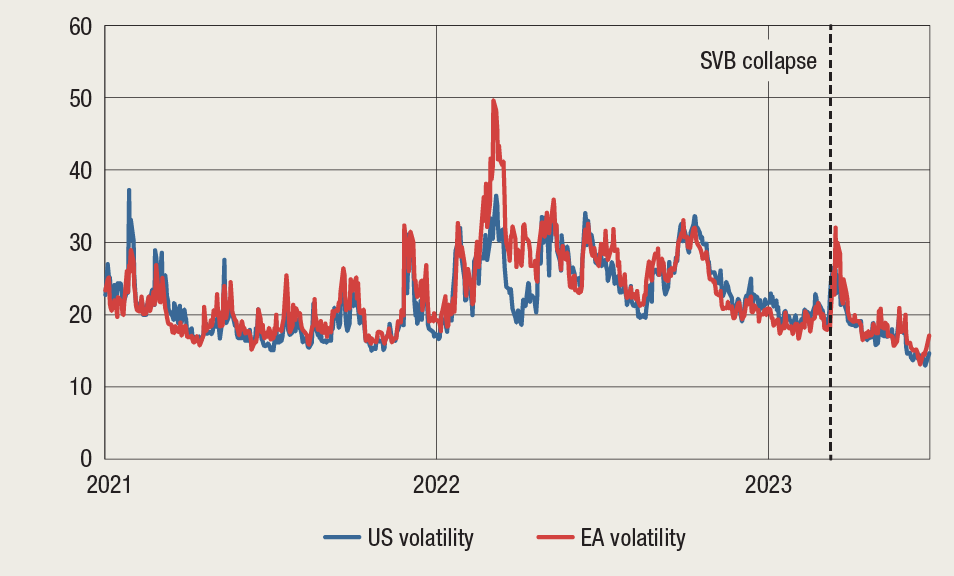

Persistent inflationary pressures and the possibility of sudden instability in parts of the financial system could trigger a disorderly decline in prices on the financial markets. Decreased inflationary pressures contributed to the drop in volatility on the financial markets (Figure 12), but changes in expectations regarding developments in inflation and monetary policy response, paired with fear of recession, could lead to market turmoil and result in disorderly revaluation of financial assets. Among other things, a stronger-than-expected economic slowdown could increase defaults on issued corporate bonds, while the tightening of lending conditions and reduced access to financial markets could cause highly indebted non-financial corporations to face more severe difficulties in financing their obligations. For example, in the US, a decrease in the amounts of newly-issued corporate bonds with higher yields (bonds of riskier enterprises) has been observed on the market, which is why some non-financial corporations are being forced to borrow under more stringent terms or give up on refinancing. The slowdown on the aforementioned market could spill over to the euro area and additionally increase the price of borrowing.

Figure 12 Unexpected shocks are increasing market volatility

Note: The volatility of the US market is shown using the VIX index, while for the euro area (EA), the VSTOXX volatility index was used.

Source: Bloomberg.

3. Recent macroprudential activities

The upward phase of the financial cycle and the related increase of cyclical systemic risks continued in the first half of 2023 despite the moderate tightening of financial conditions and the economic slowdown. Against such a backdrop, the CNB took measures to further enhance the resilience of credit institutions, announcing that it would lift the countercyclical buffer rate to 1.5%, taking into account the high profitability and the favourable capital position of the banking sector. Regular periodical review of the adequacy of risk weights for real estate-secured exposures has shown that the risk weights prescribed by the CNB are commensurate with actual and expected losses under such exposures. Based on an analysis of the systemic materiality of third countries for the banking system in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro were identified as material third countries, while the analysis of cyclical risks in these countries has shown that there is no need for regulatory action by the CNB.

3.1 Announcement of a countercyclical buffer rate increase from 1% to 1.5%

In June 2023, the Croatian National Bank announced that it would raise its countercyclical buffer rate to 1.5% amid continuously high cyclical systemic risk indicator values. This is the third increase of the aforementioned instrument in less than a year and a half, after the increase of 0.5% in force since 31 March 2023 and the announced increase to 1%, effective as of 31 December 2023. The further increase of the countercyclical buffer rate to 1.5% as of 30 June 2024 will enhance banks’ resilience amid elevated cyclical systemic risks, primarily reflected in the sharp rise in bank loans to the non-financial private sector and the increase in residential real estate prices (see chapter 1 Identification of systemic risks and the explanation for buffer rate increase issued with the Decision).

A higher countercyclical buffer leaves more room for the CNB to take action with the aim of supporting the business operations and credit activity of banks should cyclical systemic risks materialise. At the same time, increased capital requirements should not have any unfavourable effects on the cost and availability of bank lending as the domestic banking system is stable and profitable, maintaining substantial capital surpluses at system level.

Table 1 Countercyclical buffer rates

Source: CNB.

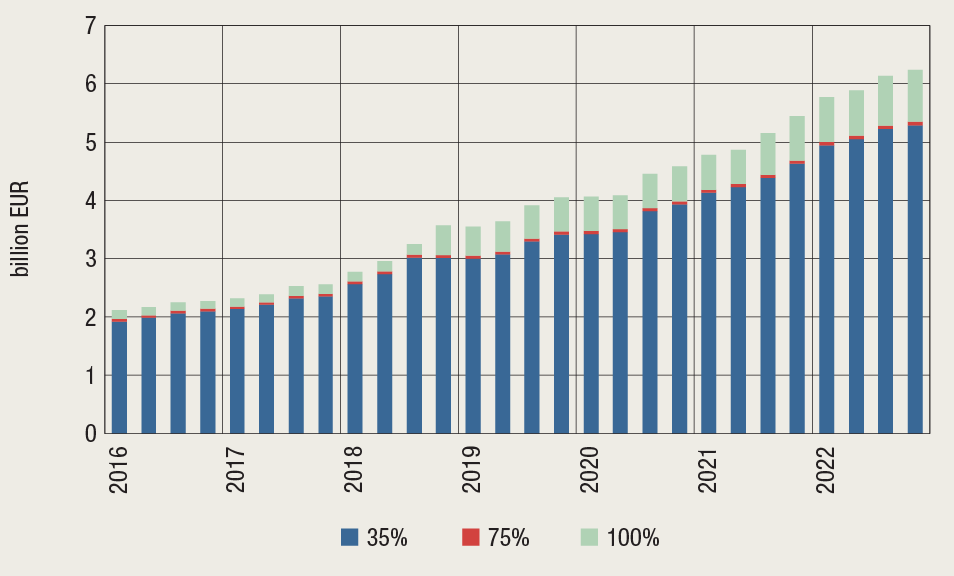

3.2. Annual assessment of appropriateness of risk weight for real estate-secured exposures

Based on the regular annual assessment, the Croatian National Bank concluded that the applicable risk weights for exposures secured by residential and commercial real estate in Croatia are appropriate and should continue to apply. A decision[6] is in force in Croatia which lays down a more stringent definition of residential property to which a preferential risk weight of 35% can be applied, prescribed by Regulation 575/2013 for exposures secured by residential property occupied by the owner. Furthermore, in exposures secured by commercial real estate property, instead of the standard risk weight of 50% prescribed by Regulation 575/2013, the aforementioned decision lays down a higher risk weight of 100% (see Table 3 in the annex). The assessment of the appropriateness of the aforementioned instruments[7] has been performed in line with binding European regulatory technical standards[8] taking into account the data on incurred losses on relevant exposures, the estimate of expected losses on these exposures and risks arising from macroeconomic developments and the situation on the real estate market in Croatia. Based on the analysis of incurred losses, current and expected developments on the real estate market in Croatia and the related systemic risks, no significant increase in losses under such exposures is expected in the following year. However, in the medium term, the aforementioned losses could increase if domestic and external macroeconomic circumstances worsen and interest rates continue to grow, resulting in a sharper fall on the real estate market (see chapter 2), which is why the application of more stringent risk weights for real estate-secured exposures in Croatia has been assessed as appropriate.

Figure 13 Exposures secured by real estate according to risk weights used

Source: CNB.

3.3. Annual analysis of third-country materiality for the banking system of the Republic of Croatia

In the second quarter of 2023, the Croatian National Bank carried out a regular annual analysis of third-country materiality for the banking system of the Republic of Croatia, identifying, again, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro as material third countries[9]. Bosnia and Herzegovina has been on the list of material third countries for the banking system of Croatia since 2016 (since an analysis of third-country materiality began to be regularly undertaken), while Montenegro was added to the list in 2020. On a consolidated basis, the exposure of the domestic banking system to the aforementioned countries mainly results from the lending activity of subsidiaries of domestic credit institutions, while direct cross-border exposures mainly refer to equity investment. In addition to the determination of material third countries, an analysis was made of the developments in systemic risks of a cyclical nature in the aforementioned countries, which has shown that there is currently no risk of excessive credit growth that would require regulatory response in relation to Croatian banks exposed to these markets.

3.4. Implementation of macroprudential policy in other European Economic Area countries

In the second quarter of 2023, most EEA member states maintained currently applicable measures. One country adopted a decision on the easing of applicable measures due to financial cycle reversal, while several others additionally tightened the measures related to the mitigation of cyclical systemic risks and risks associated with the real estate market.

The Czech Republic announced that it would lower the countercyclical buffer rate from the currently applied 2.5% to 2.25%, effective as of 1 July 2023, with the explanation that the financial cycle had entered a downturn, taking into consideration economic and geopolitical uncertainties. The decision stresses the willingness of the Czech central bank to further release the aforementioned buffer depending on the future developments in cyclical risks. In addition, the binding DSTI (debt service-to-income ratio)[10] has been lifted with the explanation that, due to higher interest rates, the upper limit on the DSTI ratio is not necessary. Other measures aimed at loan users remain in application (LTV – loan-to-collateral value ratio and DTI – debt to income ratio of the loan user).

The Netherlands announced that it would further raise the countercyclical buffer rate from 1% in application as of the end of May 2023 to 2% effective as of 31 May 2024 in response to the upward phase of the financial cycle and the developments in relevant indicators.

Ireland will raise the countercyclical buffer rate for the third time in a year, announcing the application of a 1.5% rate as of 7 June 2024, a further increase from the announced rate of 1% applicable as of 24 November 2023. A rate of 0.5% is currently applied. The latest increase is consistent with the central bank’s policy on a gradual build-up of a positive neutral countercyclical buffer rate with the aim of enhancing the resilience of credit institutions to possible future shocks.

France announced that it would introduce a sectoral systemic risk buffer of 3% to be applied to exposures to non-financial corporations under cumulative compliance with additional conditions. The measure is to take effect on 1 August 2023 with the aim of addressing the vulnerabilities associated with any possible over-indebtedness of non-financial corporations in the financial system.

Table 2 Overview of macroprudential measures applied by EEA countries and the United Kingdom

Table 3 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

-

For more information on projections, see https://www.hnb.hr/en/analyses-and-publications/regular-publications/macroeconomic-developments-and-outlook. ↑

-

On 28 June 2023, maturing liabilities arising from loans granted under targeted longer-term refinancing operations amounted to EUR 476.8bn. ↑

-

The decrease in the capital ratio is driven by transitional adjustments to the IFRS 9 in the part of the continued gradual introduction of provisions for expected credit losses under IFRS 9 in the capital (the factor of the “dynamic” component of the impact). The dynamic component enables banks to partly neutralize the impact of a subsequent increase in provisions for financial assets that have not been adjusted for credit losses. The initial transitional arrangement that covered the period from 2018 to 2022 has been extended under the CRR quick fix to last until 2024. The reduction factor of the dynamic component stood at 0.75 throughout 2022; in 2023, it stands at 0.5 and in 2024 it will amount to 0.25. Transitional adjustments amounted to EUR 110.6m in the first quarter of 2023. ↑

-

It is important to note that these estimations refer to agreeing interest rate fixing within the same credit institution and that it is possible that some of consumers refinanced their loans in another credit institution, with interest rate fixing. It is also possible that, for some such consumers, loan refinancing in other credit institutions was not primarily motivated by interest rate fixing, but by other benefits that consumers may gain when changing credit institutions. ↑

-

The maximum allowed interest rate on housing loans with a variable interest rate must not exceed the average weighted interest rate on the balances of housing loans in a given currency, augmented by one third, while the interest rate on non-housing loans with a variable interest rate must not exceed the average weighted interest rate on the balances of such loans in a given currency, augmented by a half (OG 75/2009, 112/2012, 143/2013, 147/2013, 9/2015, 78/2015, 102/2015, 52/2016 and 128/2022 and OG 101/2017 and 128/2022). ↑

-

Decision implementing the part of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 pertaining to the valuation of assets and off-balance sheet items and the calculation of own funds and capital requirements ↑

-

Under Article 11, paragraph (3) of the Credit Institutions Act, the Croatian National Bank is, within the meaning of Article 124, paragraph 1a of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013, the authority designated to assess the appropriateness of risk weights and criteria referred to in Article 125, paragraph (2) and Article 126, paragraph (2) of the Regulation. ↑

-

Commission delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/206 of 5 October 2022 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to regulatory technical standards specifying the types of factors to be considered for the assessment of the appropriateness ↑

-

The analysis was made in accordance with Article 3 of the Decision of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) on the assessment of materiality of third countries for the Union’s banking system in relation to the recognition and setting of countercyclical buffer rates (ESRB/2015/3). ↑

-

A maximum DSTI of 45% (or 50%) of the loan user’s net monthly income was in force from 1 April 2022. ↑