The increasingly obvious consequences of climate change have not only accelerated the development of climatology, but also the transformation of other disciplines, including the economy and central banking. The blog of CNB Deputy Governor Sandra Švaljek provides a brief overview of the reasons why central banks have also started with activities to combat climate change and an explanation of why this approach has no alternative. The beginning of climate action of central banks took place in 2015 when the then Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, warned financial institutions that their focus on the short and medium term in which they could not see an environmental and social tragedy on the horizon could threaten both financial stability and long-term economic prosperity. Earlier that same year, Governor Boris Vujčić made a presentation at the international conference in Shanghai about the European position on greening economic and financial systems. Central banks initially focused mainly on the possible effects of climate change on financial stability, while more attention was paid only relatively recently to the impact of climate and environment on prices. The fact that climate change through various direct and indirect transmission channels may affect individual prices or the dynamics of the general price level led the central banks to conclude that, regardless of whether the law has placed the fight against it under their competence, climate change must be addressed in order to successfully fulfil the core task entrusted to them – maintaining price stability.

In a speech given in early 2022, Isabel Schnabel, member of the Executive Board of the ECB, named the following three types of inflation induced by climate change and the climate transition: "climateflation", i.e. price spikes triggered by climate extreme events, "fossilflation", a rise in fossil fuel prices due to the introduction of a carbon tax and "greenflation", a rise in prices driven by the costs of adapting to climate change. Due to the type of goods the prices of which initially increased (energy products), recent inflation hikes demonstrated the type of inflation that might be caused by a disorderly climate transition. This was an additional reason for central banks to focus on the impact of climate-related transition risks on price developments.

"Central banks have accepted the challenge and significantly improved their understanding of the climate impact on economic developments in less than ten years, especially those developments that can affect price stability and the stability of the financial system. Such a commitment is a reason for mild optimism that, even in times of climate transition, central banks could maintain price stability through timely responses, thus contributing to economic prosperity and wellbeing", concludes in her blog Sandra Švaljek, Deputy Governor of the CNB.

Breakout year of 2015 and growing concerns

The 2008 survey in the US segmented the American public according to climate change attitudes and assessments of the need to actively combat climate change. It was shown that the public can be divided into six coherent groups – alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful and dismissive.[1] Since 2012, the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication twice a year conducts a survey on a representative sample in which it monitors changes in the population structure in terms of belonging to these groups. On the basis of the results, it can be observed that in the US, between 2012 and 2022, the share of alarmed people doubled, rising from 12 to 26 percent, and that the aggregate share of the alarmed and concerned increased significantly, from 38 to 53 percent.[2]

There are no surveys in the EU countries that systematically monitor the trends in the share of population concerned about the climate and the environment.[3] However, it is assumed that this trend is similar to that in the US, as surveys show that between 2008 and 2021, the share of the EU population who consider that climate change has become a serious problem rose from 62 to 93 percent.[4] Bearing in mind the growing awareness about climate change and the risks it entails, it is quite understandable that central banks of most countries have also become more alarmed and concerned over the last ten years, as they understand that economies and financial systems cannot remain isolated from the increasingly obvious disruptions in the natural environment, caused mainly by human activity.

The beginning of climate action by central banks as well as the Croatian National Bank should probably be dated in the year 2015. Inspired, possibly, by the Nobel Peace Prize awarded in 2007 to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and Al Gore Jr. for his climate engagement, some central banks were interested in the topic somewhat earlier, launched a first research into the economic, environmental and social consequences of climate change (e.g. Bank of Greece, 2009) and issued several influential speeches.[5] However, these activities were sporadic, atomised and, until 2015, did not have the potential to spread to other central banks and incorporate climate considerations into their key functions.

In September of that year, in his speech in London Lloyd’s, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England at the time, responded to a call from the G20 finance ministers to include the financial sector in the fight against climate change.[6] Carney asked financial institutions to look further into the future and expand their horizons. He warned them that their focus on the short and medium term prevents them from seeing an environmental and social tragedy on the horizon, and that this could threaten both financial stability and long-term economic prosperity. Mark Carney's speech was an excellent introduction to the UN Climate Change Conference COP 21 in Paris two months later, where 195 UN members agreed to adopt the so-called Paris Agreement. In addition to keeping the increase in global temperature well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, it committed countries that later ratified this agreement to provide the necessary funding to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and ensure climate-resilient development.[7] This gave all financial institutions a rather explicit task to contribute to the fight against climate change.

The Croatian National Bank did not stay away from these events and has not shown doubts as regards the need to involve financial institutions, central banks and regulators in the fight against climate change. Already in May 2015, at the 33rd meeting of the Central Bank Governors' Club of Central Asia, Black Sea Region and Balkan Countries in Shanghai, Governor Boris Vujčić gave a presentation on the European position on greening economic and financial systems. His messages were even more progressive than the prevailing view at that time – he stressed that Basel III required banks to assess the exposure of credit portfolios and their operations to environmental risks, but warned that the opportunities offered by such a requirement were not fully exploited. He assessed that monetary policy instruments could be adjusted to contribute to the greening of finances to the extent that this adjustment does not compromise the main objectives of central bank activity, namely price stability and financial stability. However, in line with the dominant view at that time, he stated that neither the Fed nor the ECB are legally obliged to take environmental risks into account.

Framework to address climate risks

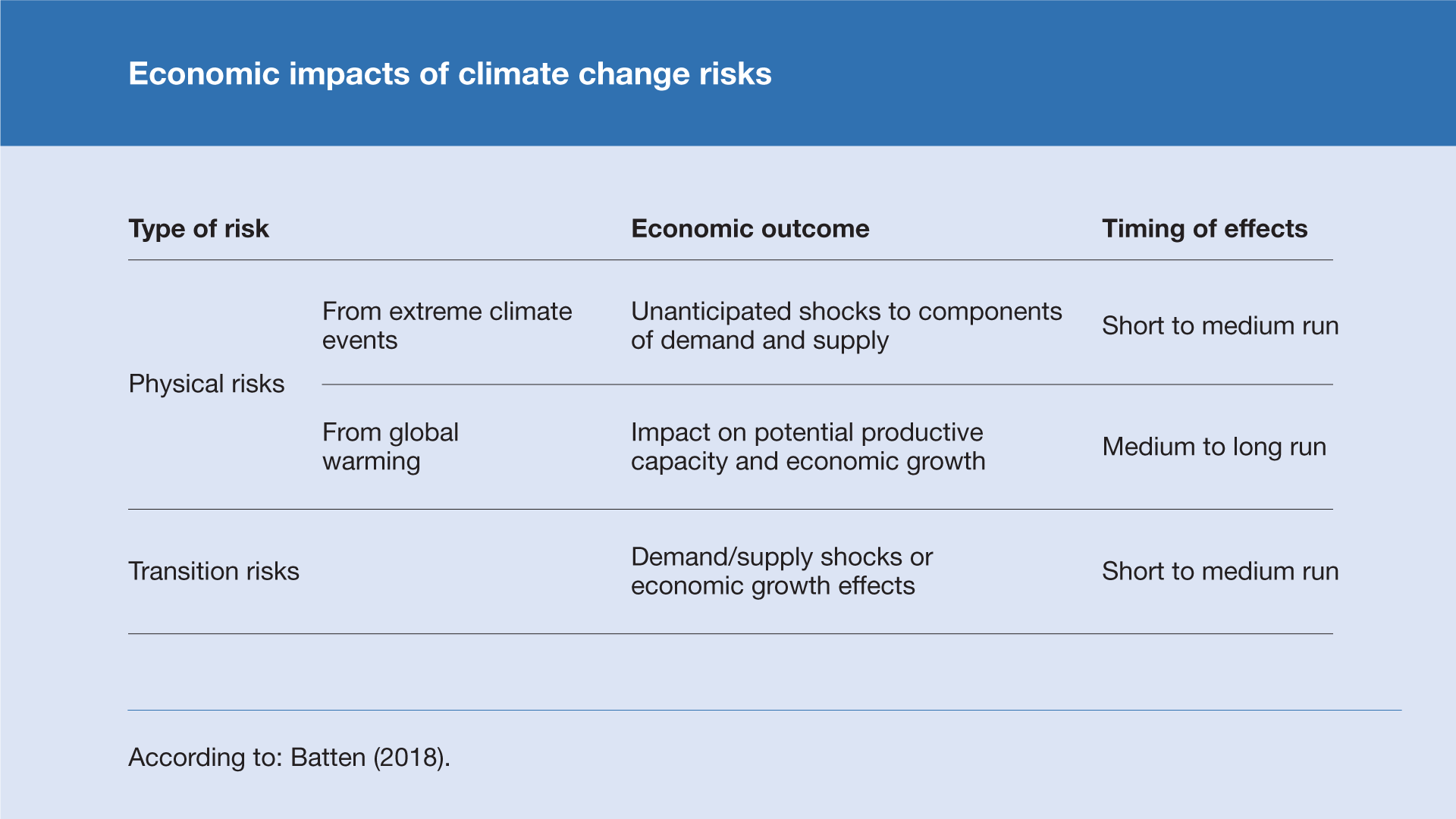

Since 2015, central banks have made remarkable intellectual efforts to better understand climate change mechanisms, enter the world of data on weather, climate and greenhouse gas emissions, understand how climate projections are produced and interpreted, and isolate the impact of climate change on economic developments and the financial system. In an effort to bring a solid structure into their research and operational engagement with the climate, they have found that climate change causes two types of risks: physical and transition. The first risks arise from physical manifestations of climate change – e.g. droughts, floods, fires, storms, heat waves or simply continuously rising temperatures, and the second risks stem from governments, businesses and consumers taking action and changing their behaviour to combat climate change or mitigate its impact on prosperity. Both types of risk are transmitted through a number of channels to economic indicators either by triggering short-term supply or demand shocks or by having a long-term and predictable impact on productivity and economic growth.[8]

Drawing on their legal powers, central banks initially focused predominantly on the potential effects of climate change on financial stability, as well as measures in the field of prudential supervision and macroprudential policy that could encourage banks to properly assess climate risks in their balance sheets and thus maintain financial stability in the context of climate change. Although reports from central banks and the Network for Greening the Financial Systems (NGFS) as well as academic articles mentioned how climate-related risks may have an impact on inflation, relative prices, predictability of price developments and inflation expectations[9], more attention was paid only relatively recently to the impact of climate and environment on prices. The fact that climate change, as can be seen, may, through various channels of direct and indirect influence, affect individual prices or the dynamics of the general price level, led the central banks to conclude that, regardless of whether the law has given them power to combat against it, climate change must be dealt with in order to successfully fulfil the fundamental task entrusted to them – maintaining price stability.[10]

The impact of climate on price stability is finally in the focus of central banks

It is assumed that the impact of climate on prices has been in the focus of central banks in recent years for several reasons. First, in these years global average temperatures reached historic peaks, leading to numerous extreme and unprecedented weather events with significant damage, human victims, falling yields and disruptions in the supply of agricultural products.[11] It has become evident that climate change is not a thing of the distant future but of the present. The cost of delaying tackling climate change could therefore become too high. Second, the latest IPCC reports on how, despite some efforts, both greenhouse gas concentrations and average global temperatures continue to increase, received the attention of the media who conveyed their message of the urgency of action by governments, civil society organisations and the business sector.[12] Generous financing of public investments and support for private investments in the climate transition and the rapid development of new technologies inspired by such reporting could lead to structural changes with non-negligible effects on prices and natural interest rates.[13] Third, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that economic and financial systems are extremely exposed to risks arising outside the economic sphere, which, as a result of globalisation, have the potential to spread to all or most of the world’s economies. Climate-related risks undoubtedly belong to such risks. They, as well as policy makers’ reactions to them, can be an additional source of change in the level and volatility of prices.[14] Finally, the recent inflation episode showed that inflation was not an economic problem of the past and revived the fear of unbridled price growth and its devastating consequences. This prompted central banks to get as clear as possible perception of whether climate change could also be one of the triggers for future price increases.

Thanks to numerous research, we know today much more about the mechanisms and the possible direction of the impact of climate change on prices than just a few years ago. But, as in a well-known phrase that combined the concepts of uncertainty and risk – apart from what we know we know, there are many things we know that we do not know or about which we are not entirely sure and, certainly, there are many things we do not even know that we do not know.

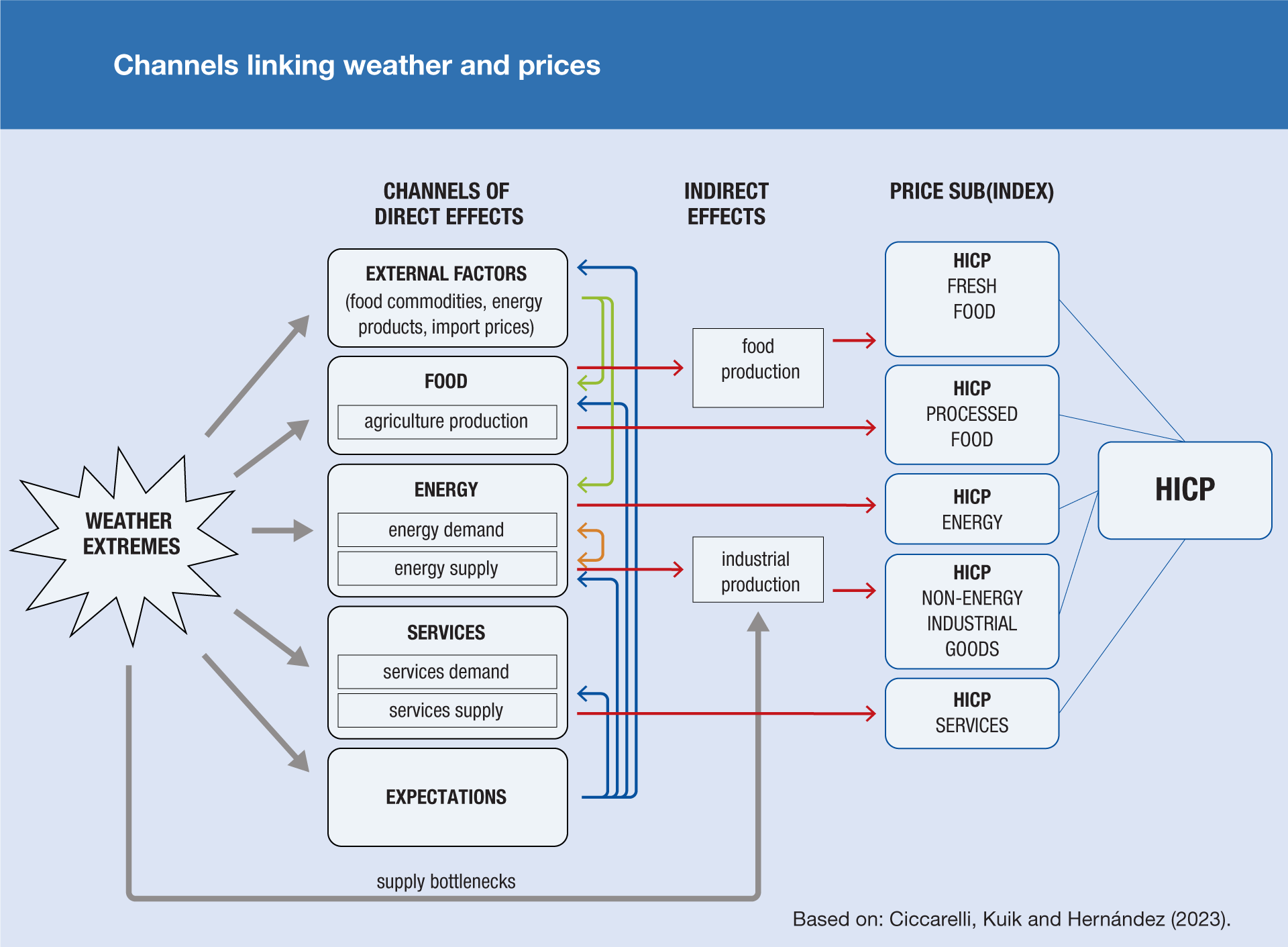

Research into the impact of climate change on prices started by shedding light on the impact of physical climate risks, i.e. weather disasters, on inflation. The European Central Bank published its first research on the topic already in November 2016. Its findings have shown that the impact of weather shocks on inflation depends on the degree of development of the country in which they occur, with the impact on price growth being stronger in less developed countries in which agriculture provides food to the population and is also the main source of income, which often have fewer resources to cope with natural disasters.[15] The impact also depends on the type of disaster, so droughts can affect food prices over a several-year period, while the impact of floods and storms is short and low. The heterogeneous impact – both in terms of direction and in terms of intensity – has also been confirmed in a recent study of the shock of temperature increases and variability in four European countries, and the impact has also proved to depend on the season in which the temperature increase or increase in variability is taking place.[16] Heterogeneity in the impact stems from different channels through which higher temperatures or temperature oscillations are affecting inflation measures – in some countries and some seasons weather conditions affect, for example, the supply of agricultural products, in some they affect energy demand or supply, while they may also change the supply of certain services by means of influencing labour productivity. The complexity of the mechanism of direct impact of weather on the prices of certain groups of products (notably food and energy) and on the price of services (illustrated in the figure below) adds to the indirect impact of the prices of these products and services on the prices of other products and services, making it extremely difficult to predict the final impact of weather extremes on the general price level and its evolution.

A paper by Tihana Škrinjarić that has recently been published in CNB publications is the first research contribution of the Croatian National Bank to the assessment of the impact of physical climate risks on prices in Croatia.[17] The paper shows that, among weather extremes, droughts have the strongest impact on inflation in Croatia, leading to a more sustained increase in prices. Although the paper does not find any statistically significant impact of heat stress on inflation, it is estimated that this effect might be negative, which might indicate that heatwaves mostly affect prices through a decrease in demand. This finding coincides with the findings of empirical research by Filippo Natoli from the Bank of Italy, conducted on the basis of daily meteorological data for the US since 1970. The results of that research have shown that demand-side effects have a dominant influence on the response of key economic variables to unexpected temperature variations, but also that the fall in the consumer price index and the fall in GDP are caused by both exceptionally warm and exceptionally cold days.[18]

The links between transition climate risks and prices are even more difficult to assess, as transition climate risks include many reactions of economic operators to climate change that are completely unpredictable, ranging from measures adopted by climate policy makers, through private and public sector investments to develop new technologies to combat greenhouse gas emissions and defend themselves from damage caused by climate change, to changing consumer preferences. An additional element of climate-related risks is the uncertainty that is caused by all these changes, which can also affect prices. Due to complexity, the assessment of the impact of transition climate risks on prices is usually made gradually, by assessing individual interdependencies and with many assumptions and simplifications. Most research has so far focused on the modelling of the link between prices and the introduction of a carbon tax as the main instrument of climate policy, i.e. the link between prices and additional investments driven by the climate transition, while the links between prices and other components of climate risks are still little known.

Interest in the impact of transition climate risks on prices has significantly increased since the recent revival of inflation. While it was widely recognised that a basic climate policy instrument could and should be a carbon tax that would heavily burden fossil fuel prices and thus incentivise the transition to renewable fuels, it was previously assumed that the impact of introducing such a tax on the overall price level could be moderate and one-off, so that it would not require a response from central banks.[19] Preliminary ECB research showed that in a scenario of an orderly climate transition, where governments gradually and predictably raise carbon taxes and technologies are slowly transformed, transition risks have no significant impact on prices and output. In a scenario of a disorderly and sudden transition, the jump in energy prices leads to a slight increase in the general price level relative to the baseline scenario, but the low intensity and short duration of this effect leads to the conclusion that a central bank’s response to such a price increase would only unnecessarily slow down economic activity. Pre-pandemic studies highlight the effects of forces that could lead to a fall in natural interest rates, which could require non-standard monetary policy measures to be applied due to the bottoming out of interest rates.[20], [21]

The emergence of inflation in the post-pandemic period and especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine gives rise to some reversal in the expectations of the effect of the climate transition on prices, which was supported by an influential speech by Isabel Schnabel in January 2022. In that speech, she stresses that climate policies could lead to a more lasting increase in energy prices and their incorporation into the general price level. She concludes that the green transition could undermine price stability to the extent that central banks cannot tolerate, both in duration and intensity.[22] Subsequently, in her March 2022 speech, Schnabel elaborates on this topic, designating three types of inflation induced by climate change and the climate transition, that is climateflation, i.e. price rises driven by extreme climate events, fossilflation, increases in fossil fuel prices due to the introduction of carbon taxes and greenflation, price increases due to climate change adaptation costs.[23] These speeches show that, due to the type of goods the prices of which initially increased (energy products), recent inflation hikes demonstrated the type of inflation that might be caused by a disorderly climate transition. This was an additional reason for central banks to focus on the impact of climate-related transition risks on price developments.

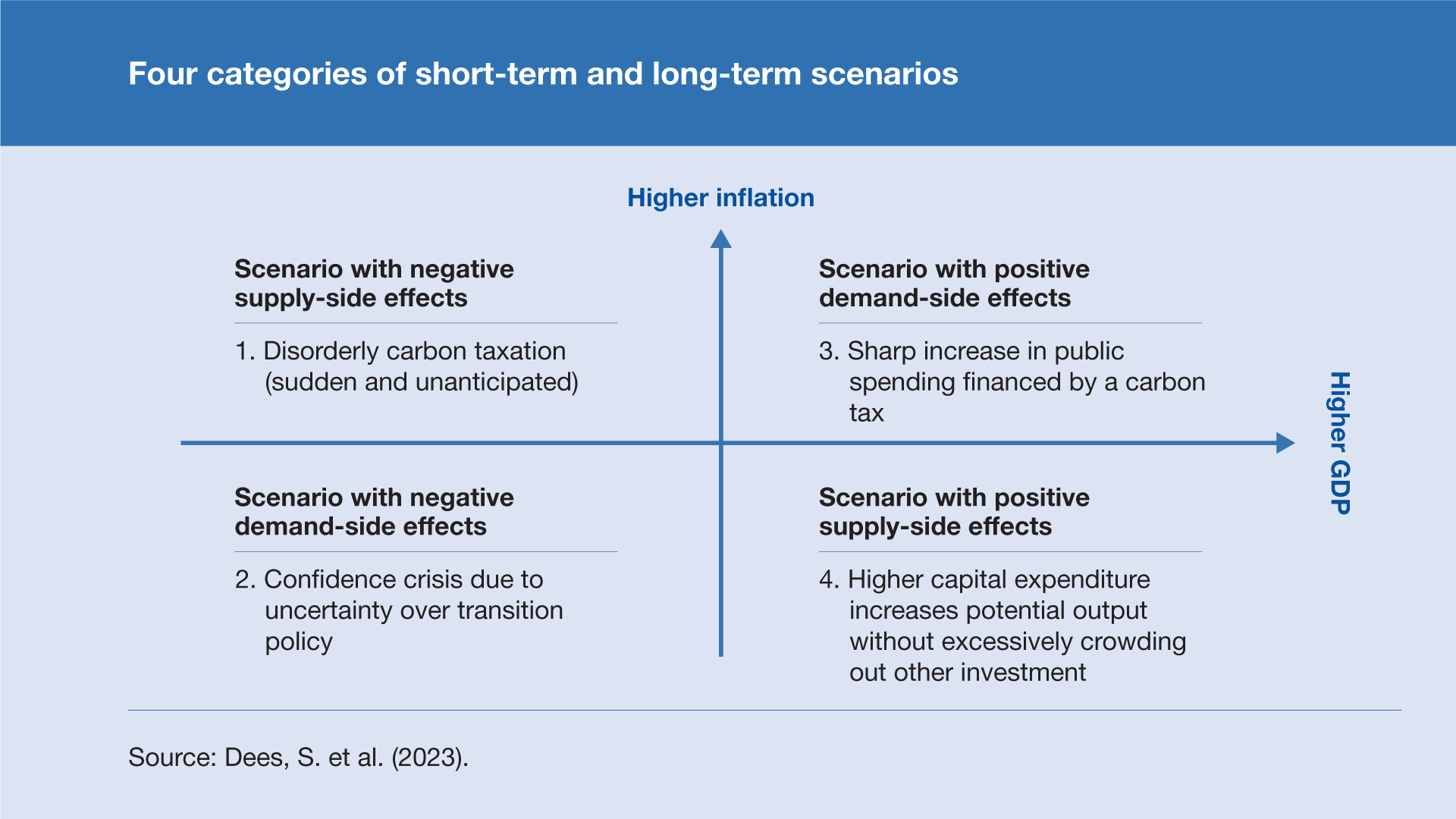

To gain a deeper and more elaborate insight into possible effects of the climate transition on prices, in March 2023 researchers from the Banque de France announced estimates of the direction of the impact of transition shocks on prices and economic activity in four different transition scenarios (see the figure below).[24] These scenarios were chosen with the intention to illustrate the basic features of sudden but equally possible climate transitions that may have significant effects on economic activity and prices. Depending on the type of scenario, researchers from the Banque de France show that the climate transition may have completely different consequences – from a sharp rise in inflation and economic slowdown to falling inflation and accelerating growth. From the monetary policy perspective, an important message of this research is that the strongest upward pressure on prices can be expected in the event of a delayed and unexpected surge in the carbon price, as well as in the event of a too slow transition to green technologies, while hesitancy in the implementation of the transition policy may amplify volatility in inflation and growth.

The analysis of transition scenarios carried out in the Banque de France reconciled and combined previous reflections on the possible economic effects of the transition. It has shown that, in various variants and combinations of shocks, they may be small and large, positive and negative for economic growth, may lead to temporary but also to lasting pressures on inflation, and that these pressures can act in both directions. Although it would be easier if the certainty about the effects of the transition were greater, it is ultimately not necessary to know the exact effect of the transition, but to get a grasp of the mechanisms that it initiates and thus affects economic indicators.

The increasingly obvious consequences of climate change have not only accelerated the development of climatology, but also the transformation of other disciplines, including the economy and central banking. Central banks have accepted the challenge and significantly improved their understanding of the climate impact on economic developments in less than ten years, especially those that can affect price stability and the stability of the financial system. Such a commitment is a reason for mild optimism that, even in times of climate transition, central banks could maintain price stability through timely responses, thus contributing to economic prosperity and wellbeing.

-

Maibach, E. W., Leiserowitz, A., Roser-Renouf, C. and Mertz, C. K. (2011): Identifying Like-Minded Audiences for Global Warming Public Engagement Campaigns: An Audience Segmentation Analysis and Tool Development, PLoS ONE 6(3): e17571. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017571 ↑

-

See: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/. ↑

-

A comparative survey for European countries, Israel and Russia, which was carried out on the basis of data from the European Social Survey for 2016, distributed the population of 23 countries under review to 18% of the engaged, 18% of the pessimistic, 42% of the indifferent and 21% of the doubtful. See: Ondřej Kácha, Jáchym Vintr, Cameron Brick, Four Europes: Climate change confidences and attitudes PREDICT Behavior and policy preferences using a latent class analysis on 23 countries, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume 81, 2022, 101815, doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101815. ↑

-

See: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/citizens/citizen-support-climate-action_en#previous-surveys. ↑

-

Arseneau D.M., Drexler, A. and Osada, M. (2022): Central Bank Communication about Climate Change, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-031, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, doi/10.17016/FEDS.2022.031. ↑

-

Carney, M. (2015): Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – climate change and financial stability, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2015/breaking-the-tragedy-of-the-horizon-climate-change-and-financial-stability. ↑

-

On the Paris Agreement, see: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement. ↑

-

For details, see Batten, S. (2018): Climate change and the macro-economy: a critical review, Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 706 ↑

-

On the impact of climate risks on key macroeconomic variables, see e.g.: NGFS (2020): Climate change and monetary policy: initial takeaways, June 2020. ↑

-

Schnabel, I. (2021) in her speech From market neutrality to market efficiency, points out, for example: "In fact, as I have argued previously, our primary mandate requires us to take climate change into account if its consequences pose a threat to price stability in the euro area." ↑

-

See e.g. the evolution of the global average temperature on: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/. ↑

-

Public attention was particularly drawn to the Summary for policymakers of the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group published in March 2023. See at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/. ↑

-

The March 2023 magazine Finance & Development, based on the research by M. K. Brunnermeier, highlighted six structural changes that could have a decisive influence on monetary policy in developed countries over the long term. It put the green transition first, which could lead to an increase in the natural level of interest rates due to increased investment demand. ↑

-

In the European Union, in November 2019 the European Parliament declared a climate and environmental emergency and called on the European Commission, as well as all members of the European Union and all institutions, to take action to fight and contain this threat before it is too late. This declaration and its demands were temporarily overshadowed by the pandemic crisis that followed shortly afterwards, but it remains in place and is the basis of demands that actions of all institutions and their policies take into account climate and environmental concerns. ↑

-

Parker, M. (2016): The impact of disasters on inflation, ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1982. ↑

-

Ciccarelli, M., Kuik, F. and Hernández, C. M. (2023): The asymmetric effects of weather shocks on euro area inflation, ECB Working Paper Series, No. 2798. ↑

-

Škrinjarić, T. (2023): What are the short-to-medium-term effects of extreme weather on the Croatian economy? CNB Working Papers W-70. ↑

-

Natoli, F. (2023): The effect of extreme temperatures on the US economy and on the conduct of monetary policy, SUERF Policy Brief, No. 574. ↑

-

See e.g. Batten, S., Sowerbutts, R. and Tanaka, M. (2016): Let’s talk about the weather: the impact of climate change on central banks, Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 603; R. Moessner (2022): Effects of Carbon Pricing on Inflation, CESifo Working Paper No. 9563. ↑

-

See ECB (2021): Climate change and monetary policy in the euro area, ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 271. ↑

-

In an article from the end of 2022, Angeli et al. offer a much more balanced view on the impact of climate change on the natural interest rate, noting that there are many potential channels for this impact and that, in addition to downward forces, e.g. a rise in the risk premium, there are also those leading to its increase, e.g. productivity growth and additional green investments. See: Angeli et al. (2022): Climate change: possible macroeconomic implications, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2022 Q4. ↑

-

Schnabel, I. (2022): Looking through higher energy prices? Monetary policy and the green transition, Remarks at a panel on "Climate and the Financial System" at the American Finance Association 2022 Virtual Annual Meeting, Frankfurt am Main, 8 January 2022. ↑

-

Schnabel, I. (2022): A new age of energy inflation: climateflation, fossilflation and greenflation, Speech at a panel on "Monetary Policy and Climate Change" at The ECB and its Watchers XXII Conference, Frankfurt am Main, 17 March 2022. ↑

-

Dees, S., Wegner, O., de Gaye, A. and Thubin, C. (2023): The transition to carbon neutrality: effects on price stability, Bulletin de la Banque de France, 245/3, March – April 2023. ↑