Makroprudencijalna dijagnostika, br. 13

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected based on calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then combined in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, including the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. In addition, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of an event that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a large part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of the risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1. Identification of systemic risks

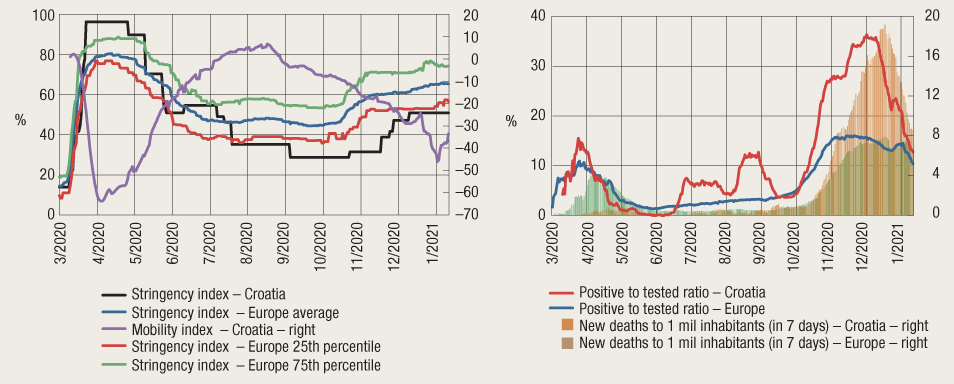

Total exposure to systemic risks in the fourth quarter of 2020 remained high. Compared to the third quarter estimate (as published in the Risk map in the publication Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 12), there was an increase in short-term risks in the non-financial sector (Figure 1). The beginning of vaccination against the coronavirus stirs hope that the pandemic will be contained by mid-2021, however, its slow rollout throughout the EU increases the risk of yet another wave of COVID-19 at mid-year. Potential new tightening or extension of the measures in force and the possibility of another poor tourist season fuel further uncertainty, particularly in the private sector, while the expenditures associated with the earthquakes in Zagreb and Pokuplje put a pressure on government finances.

Figure 1 Risk map, fourth quarter of 2020

Note: The arrows indicate changes from the Risk map in the third quarter of 2020 published in Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 12 (October 2020).

Source: CNB.

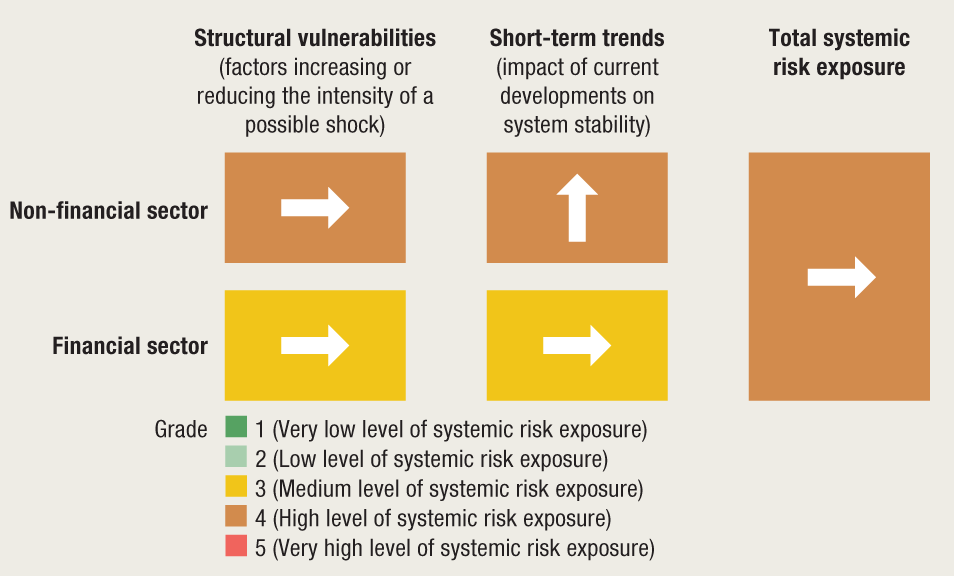

From June to end-2020, Croatia was one of the countries with the least restrictive epidemiological measures in Europe, but also a country with a much bigger number of newly infected persons and number of deaths in relation to the number of inhabitants (Figure 2). Until early June, Croatia was one of the countries with the strictest epidemiological measures in Europe but after the summer it became one of the countries with the most lenient measures. A more permissive approach generally has smaller negative effects on the economy in the short-term; however, economic developments were negatively influenced by changes in consumer behaviour fuelled by the fear of contagion (for example, decreased mobility started much before the introduction of stricter epidemiological measures). As the number of newly infected persons and the number of deaths from the coronavirus rose sharply after September and as the capacity of the health care system was stretched close to its maximum, the authorities decided to introduce somewhat stricter epidemiological measures, albeit with a small time gap. At the turn of the year, the severity of the epidemic in Croatia lessened.

Figure 2 COVID-19 in Croatia and Europe: stringency index, mobility index, new cases and deaths

|

Source: COVID_data: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus, mobility index: Google LLC "Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Report" Blavatnik School of Government - University of Oxford, data as at 15 January 2021, processed by the CNB. |

A devastating earthquake that struck central Croatia at the end of the year (with the magnitude of 6.2 on the Richter scale) caused several deaths and big losses to the housing stock in that part of the country. Due to the proximity to the epicentre, the buildings in and around Zagreb that had been hit by the earthquake in March (with magnitude of 5.5 on the Richter scale) were also affected and suffered further damage. Since no systematic reconstruction of the country’s capital has started yet, most of the reconstruction-related expenditures are still to be incurred; however, it is certain that the damage caused an enormous loss in property value. According to estimates of the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Zagreb, the material damage caused by the earthquake stands at HRK 85.9bn (23.4% of GDP in 2020) while the costs of short-term reconstruction of the earthquake damage in Zagreb amount to HRK 34.6bn (9.4% of GDP in 2020), with estimates of the damage caused by the earthquake in Pokuplje not being available yet.[1]

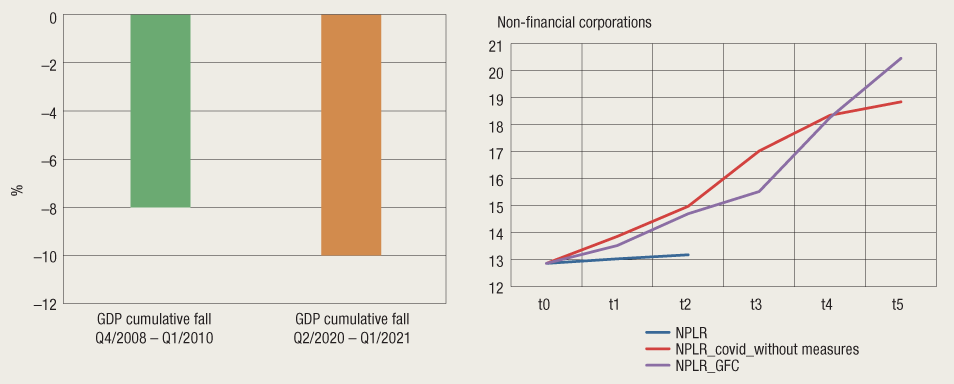

The decline in economic activity in 2020 might be sharper than that in 2009 caused by the global financial crisis. Although the year 2021 is expected to see economic recovery, the intensity of recovery is still uncertain. According to the CNB December 2020 forecast (Macroeconomic Developments and Outlook No. 9), the decrease in GDP in 2020 is expected to come to 8.9%, placing Croatia in the group of the hardest hit EU countries (the EU economy is expected to fall by 7.4% in 2020[2]), and it is expected to grow by 4.9% in 2021. The CNB projection is based on the assumption of a normalisation of the epidemiological situation and the lifting of most of the measures in Croatia and its major trading partner countries by mid-2021, which seems like a reasonable assumption at the moment although it may not necessarily materialise. Therefore, the projections of economic developments in 2021 are highly sensitive to the developments in the epidemiological situation (such as, will there be a new wave or a new strain of the coronavirus, what is the efficacy of the vaccine, how long will the epidemiological measures last?). Although consumer and business expectations in construction held steady above the long-term average and were in manufacturing at the level of the long-term average, business expectations in the trade and services sector continue to be much lower.

Financing conditions remained extremely favourable owing to developments in the international financial markets and domestic monetary policy measures. The CNB took decisive measures in the first half of 2020 and successfully stabilised the domestic financial markets, while no significant pressures were present in the domestic foreign exchange market in the second half of the year, which helped maintain favourable financing conditions for all sectors. The value of assets in the domestic non-banking financial market, particularly that of investment funds, recovered, fuelled by increased net inflows but also by positive market developments, while at the same time, the domestic stock market recorded increased turnover. The stabilisation of the conditions in different segments of the financial market (foreign exchange, money, bond and stock market) is mirrored in the index of financial stress that fell to the usual pre-crisis level. In addition, in the second half of September, Standard & Poor's confirmed that Croatia was maintaining the investment grade rating (BBB-/A–3), with stable outlook.

To mitigate the effects of the shock caused by the pandemic in 2020, the government introduced a line of measures to alleviate the financial position of companies, which led to a short-term sharp deterioration in government finances. Until end-2020, taxes and contributions exemptions amounted to 3.7% of GDP (see Box 1

What is behind the macroprudential measure on a temporary restriction of distributions?), which, together with unfavourable effect of the fall in economic activity, led to a sharp increase in general government expenditures. The financial position of the government was alleviated by an increased use of EU funds, but the rise in expenditures was accompanied by a cyclic fall in government revenues, which, combined, led to a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit and public debt. Under Government projections, which are also based on the expectation of normalisation of the epidemiological situation, such trends are expected to come to a halt in 2021. Regardless of whether these projections will materialise or not, the public debt that was excessive even before the pandemic will continue to pose a pronounced structural risk over a medium term.

Risks in the non-financial private sector rose further in the fourth quarter from an already elevated level, with corporate vulnerability in affected activities largely depending on economic recovery dynamics and the efficacy and duration of the measures aimed at mitigating the economic impacts of the crisis. The buffers accumulated in the years prior to the crisis helped companies to be more resilient when the corona crisis hit, and together with the package of government measures, enabled them to weather the main challenges in 2020. In the first half of the year, companies eased liquidity pressures by using the moratoria on the existing loans and new liquidity loans, with many companies receiving direct government support to finance a part of their obligations. However, the situation for companies in the services activity might become unsustainable, even with the government assistance provided.

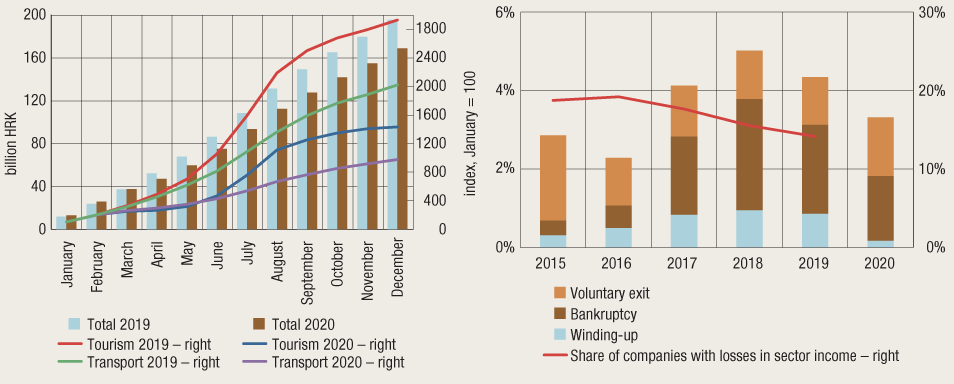

Data on fiscalisation suggest that companies witnessed a sharp fall in revenues in 2020, while their results in 2021 will depend on the speed of recovery and their adjustment capacity amid new operating conditions. The total number of fiscalised accounts in 2020 fell by approximately 13% from 2019, roughly the same as the possible fall in this sector’s operating income. This is a somewhat bigger fall than that in the crisis year 2009, although this time the fall in income is very unevenly distributed across different activities, with tourism and services recording a much bigger fall. The normalisation of the business of the corporate sector and the reduction of the sector’s liquidity and solvency risk can only happen once the pandemic is halted and the measures for its containment are lifted. However, on the one hand, there is a danger that if companies are left too soon to cope on their own on the market, which had shrunk substantially in 2020 or in some cases disappeared completely, this might lead to some of them closing and to unemployment growth. On the other hand, one fifth of companies in Croatia keep on generating losses; in 2019, they accounted for approximately 14% of the total income of the sector. The epidemic and the earthquakes in 2020 slowed down court proceedings and consequently the exit from the market of companies with unsustainable operations was also slower. The resolution of the issue of unsustainable, zombie companies is essential for the transformation of the corporate sector as it frees the resources for sound companies that will propel future growth (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Fiscalised receipts in 2020 and distribution of the manner of companies’ exit from the market

Note: The methodological break in the series of bankruptcies since 2016 relates to a change in the rules for corporates that do not submit annual financial statements.

Sources: Tax Administration and FINA (data processed by the CNB).

The uncertainty regarding the duration of the health crisis and economic recovery leads to uncertainty regarding future developments in employment and wages, with affects the growth in loans to the household sector. The fall in consumer optimism was accompanied by a fall in household demand for loans, with only housing loans continuing to grow, driven by the subsidy programme. The value of the total real assets of households decreased considerably after the two strong earthquakes, while the relatively high price of real estate makes it less accessible.

The developments in the real estate market were strongly influenced by the government subsidy programme. The currently record high level of the average price of real estate can also be attributed to the APN (Agency for Transactions and Mediation in Immovable Properties) housing loan subsidy programme. Apart from the subsidies, the activity in the real estate market in Zagreb is also influenced by factors such as favourable financing conditions, a drop in the number of tourists, abandonment of the city centre due to safety concerns associated with old buildings built prior to the introduction of anti-seismic construction regulations and reduction of office capacities led by the belief that remote work arrangements will continue even after the pandemic is over.

The liquidity and credit potential of the banking sector reached the highest levels ever, enabling further smooth operations of banks and domestic lending. Fuelled by expansionary monetary policy of the CNB, the daily surplus of free kuna reserves of the domestic banking system had reached a record high by the end of 2020, while system liquidity measured by the liquidity coverage ratio held steady at high levels, with not a single bank recording an LCR below 100% in 2020 although the supervisor permitted its use under stress conditions of the crisis.

Rising banking sector capitalisation in the crisis year 2020 was achieved by a combination of supervisory measures and regulatory changes. Driven by CNB order on maintaining the profit generated in the previous year and its inclusion in the capital and other regulatory changes (particularly the adoption of Regulation (EU) 2020/873 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards certain adjustments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the so-called CRR quick fix), the common equity tier 1 capital ratio reached a record 24% at the end of September. Also, prompted by persisting uncertainties regarding the effect of the current emergency health and economic conditions on the business of credit institutions in the Republic of Croatia, the CNB issued in January 2021 a Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions (see Chapter 3.1 and Box 1 What is behind the macroprudential measure on a temporary restriction of distributions?), thus additionally strengthening shock buffers.

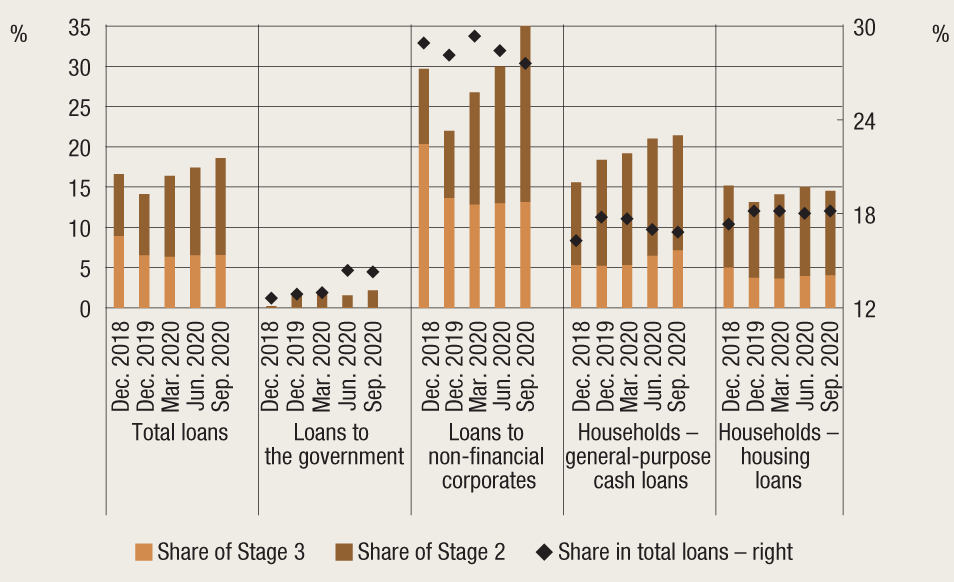

A range of economic policy measures aimed at alleviating the effects of the pandemic postponed facing the potential risks to banking system resilience, which threaten the banking system primarily by way of credit risk. In the third quarter of 2020, credit risk continued to materialise in performing exposures. The growth of loans in Stage 2 continued; they are estimated to witness an increase in credit risk since initial recognition of the instrument, with its share in total loans reaching 12% (from 7.6% at the end of 2019), influenced by developments in the segment of non-financial corporations (rising from 8.4% at the end of 2019 to 21.9%). Owing to the adjustment of the rules on classification relating to granted moratoria and growth in new exposures, the share of non-performing loans (Stage 3) in total loans continued to hold steady. Thus, in the first nine months the share of total bank loans with increased credit risk rose from 14.1% to 18.6% (Figure 4).

Bank credit risk was further driven by growth in exposure concentration (Figure 4). The growth in bank exposure to the central government mirrors increased government demand for financing. Also, unlike the previous crisis when yields on placements to the government were much higher, the increase in the share of exposures to the government in bank portfolios has a negative impact on bank profitability, already suffering from persistently low interest rates. Bank assets also witnessed an increase in the share of the hardest hit companies reflecting their efforts to finance their liquidity needs while less affected companies increased liquidity surpluses and deposited them with the banks. As regards the household sector, unsecured general-purpose cash loans saw an increase in the share of non-performing loans in total loans, while housing loans have not witnessed any significant materialisation of credit risk. However, the real estate market in Croatia, particularly if activities outside APN are observed, was marked by low liquidity and collateral marketability. The quality of loans to the private sector was also temporarily supported by the agreed moratoria on credit obligations and by a suspension of foreclosures in the household sector from mid-April to mid-October.

Figure 4 Loan quality by portfolio and share of credit portfolio in total bank loans |

Note: Loans in Stage 2 relate to performing loans witnessing a considerable increase in credit risk and loans in Stage 3 relate to non-performing loans witnessing a loss.

Source: CNB.

Thus far, the banks were successful in covering the increase in the credit risk by operating profits, with profitability, although smaller, remaining positive. Bank profit in 2020 could amount to half the profit generated in 2019. Lower profit, coupled with a simultaneous growth in the balance sheet, led to a fall in profitability indicators so that at the end of September 2020, the annualised return on average assets (ROAA) stood at 0.8% and the annualised return on average capital (ROAE) was 5.5%. In addition to rising credit risk, bank earnings were also negatively affected by persistently low interest rates, which reduce the net interest rate margin, while the costs of operations were stable. The challenges to bank profitability are likely to be present in the next year as well, given that the effects of the crisis were largely postponed by economic policy measures.

2. Potential risk materialisation triggers

Prolonged duration of tight epidemiological measures weakens the ability of the private sector to repay debts and increases the risk to corporate solvency. The initial impact on corporate balance sheets was mitigated by a fast economic policy response, enabling companies to withstand liquidity pressures. However, credit risk continued to grow in this segment despite a considerable inflow of public funds.

Further growth in the prices of real assets, despite the worsening of fundamentals, leads to an increased risk of a sudden and strong contraction of asset prices, which would prompt bank losses. Slower recovery in 2021 would result in a larger number of delinquent clients, collateral activation and pressure on the already diminished earnings of banks. Therefore, even though the risks in the financial sphere have not posed a threat so far, they should not be overlooked.

An efficient response to the pandemic is the key to fast economic recovery of the private sector, but it has an unfavourable impact on long-term sustainability of public finances that should be targeted as soon as recovery is on track. Given the relatively slow rollout of vaccination, the emergence of new, more contagious strains of the coronavirus raises the question of the efficacy of the existing vaccine. As regards economic policy measures, a premature lifting of support measures might lead to turbulence in the financial markets, but their prolonged retention on the other hand results in an increase in public debt, which then raises the issue of its sustainability.

3. Recent macroprudential activities

The rise in systemic risks exposure arising from the shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic prompted the Croatian National Bank to issue, in addition to a range of previously taken coordinated monetary and supervisory measures, a temporary macroprudential decision on the restriction of distributions in 2021. In addition to this measure and the regular macroprudential policy measures relating to capital buffers, amendments were also made to the legislative framework for the implementation of macroprudential policy arising from the transposition of the provisions of CRD V into the Croatian legislative framework. As the relevant macroprudential authority, the Croatian National bank continues to monitor on a regular basis the economic and financial developments and will act in the area of macroprudential policy where necessary and in line with the monetary policy and supervisory (microprudential) measures.

3.1. Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions

In January 2021, as the authority competent for macroprudential policy implementation in the Republic of Croatia, the Croatian National Bank issued a Decision temporarily restricting distributions by credit institutions. Under this decision, until 31 December 2021, credit institutions may not make dividend distributions, create obligations to make dividend distributions, redeem own shares, award variable remuneration to identified staff whose professional activities have a material impact on an institution's risk profile and make other forms of distributions. The decision is temporary and the Croatian National Bank will review, by 30 September 2021 at the latest, the existence of the grounds that prompted the adoption of this Decision and will accordingly adjust the duration of the decision or decide on its earlier lifting.

The purpose of the decision is to increase the resilience of credit institutions and maintain overall financial system stability amid persisting high uncertainties regarding the impact of current extraordinary health and economic conditions on the business of credit institutions. The Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions thus builds on the supervisory measure from March 2020, when credit institutions were ordered to withhold the net profit generated in 2019 and to adjust disbursements of variable remuneration adequately. Although the sharp contraction of the economy in 2020 is expected to be followed by recovery in 2021, the negative risks that might endanger it continue to be considerable (see Chapter 1). In addition, a number of measures of support to credit institutions and their clients are still in force. These measures mitigated the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity in the Republic of Croatia, due to which the real magnitude of the crisis is not yet evident on the balance sheets of credit institutions (see Box 1).

With the adoption of the Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions, the Croatian National Bank is also in compliance with the provisions of the Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board on the restriction of distributions during the COVID-19 pandemic (see 3.7.1).

Box 1 What is behind the macroprudential measure on a temporary restriction of distributions?

The macroprudential measure on the temporary restriction of distributions in 2021 contributes to financial stability maintenance by temporarily suspending the distribution of profit generated by credit institutions in 2020, a profit that is partly due to public support measures and temporary regulatory changes. The simulations made by the Croatian National Bank suggest that had there been no favourable regulatory treatment, bank credit portfolios would have deteriorated more sharply and their results would have been even poorer. In view of the reduced scope of support and the expected expiry of the moratorium, the actual scope of the impact of the pandemic on the business of credit institutions will be clearer by end-2021.

Early 2021 witnessed further implementation of the range of measures of support to credit institutions and their clients introduced by economic policy makers in spring 2020 to alleviate the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity (for more details on the measures of support to the economy in the Republic of Croatia, see Financial Stability No. 21, July 2020 and Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 12 (October 2020).

After signs of a fall in economic activity became apparent towards the end of the first quarter, a system of measures was put into place to stabilise the liquidity and solvency of companies. High amounts of support and a very large number of moratoria granted provided temporary relief to companies and households and alleviated and deferred the impact of economic turmoil on bank balance sheets. Amid rising uncertainty regarding the financial position of banks, the regulators of the financial sectors across Europe instructed financial institutions to refrain from distributions of profits. The aim is to strengthen their capital position and thus create the preconditions for the further lending necessary for economic recovery and mitigation of the risks to financial institutions solvency.

The measures taken by national regulators in Europe, the European Central Bank and the European Systemic Risk Board, were channelled to all credit institutions equally, irrespective of their risk profile and capital position, which is appropriate in the crisis situation when it is not possible to make an immediate and full assessment of the impact of the crisis on individual institutions. The ESRB Report on system-wide restraints on dividend payments, share buybacks and other pay-outs states that despite certain shortcomings of such a linear measure, it is justified because of the key function that financial institutions hold in the economy and the wide range of direct and indirect support received by them during the pandemic. It underlines the importance of a unified action on system level in order to avoid any stigmatisation of institutions that decided to restrict distributions on their own, either as a precautionary measure or due to actual problems. Amid persistent uncertainty, such restrictions are to be prolonged in 2021 in the same or a slightly modified form (see chapter 3.6.1).

How strong are the measures directly or indirectly supporting bank operations in Croatia?

The highly expansionary monetary policy pursued by the Croatian National Bank in 2020 made it possible for the financing conditions to remain favourable despite the outbreak of the crisis, with the surplus liquidity in the banking market at the end of 2020 reaching a high 14% of GDP (having risen in one year from HRK 33bn to HRK 52bn), the exchange rate of the kuna against the euro remaining stable and interest rates mainly continuing to fall.

At the same time, the fiscal policy measures in the form of direct government support, guarantees and public loans to non-financial corporations and their employees amounted to approximately 4.4% of GDP. As shown in Table 1, the biggest support to the economy was provided in the form of support to employees in the affected activities and companies with a significant fall in income as well as various deferrals and taxes and social contributions exemptions. On the other hand, the Croatian Bank for Reconstruction and Development (HBOR) and the Croatian Agency for SMEs, Innovations and Investments (HAMAG-BICRO) provided only a small amount of guarantees and new loans to companies hit by the pandemic.

Table 1 Public measures of support to companies hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020

Sources: Croatian Employment Service, Tax Administration, HBOR, HAMAG-BICRO and GDP estimate for 2020 under December 2020 CNB monetary policy projection.

In its role of microprudential supervisor of credit institutions, the CNB soon, in March 2020, postponed some activities and relaxed the regulatory framework for the business of credit institutions in Croatia. The purpose of these measures was to enable credit institutions to continue lending to the economy amid the pandemic and where necessary to grant moratoria or restructuring of due obligations to orderly debtors affected by the coronavirus pandemic and temporarily suspend measures of forced collection and thus alleviate the negative impacts of the crisis on debtors and banks. Credit institutions were thus able to postpone the recognition of bad loans in the first year of the pandemic in the part of the portfolio that was considered orderly at the end of 2019. Bearing in mind that such relaxed regulatory treatment would put off the materialisation of the impacts of the crisis on business results, credit institutions were instructed to withhold the net profit generated in 2019, and they were also expected to adjust adequately the payments of variable remuneration (bonus and severance payments, etc.). Such an approach was confirmed by the European Banking Authority (EBA), which in early April 2020 issued its initial Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the context of the crisis caused by COVID-19 (their application was later extended to end-March 2021) and issued a recommendation on the withholding of dividend payments.

The CNB subsequently permitted credit institutions to apply the flexible treatment also to exposures to debtors affected by the earthquakes in Zagreb and Pokuplje in March and December 2020, respectively. In accordance with the EBA’s response to the second wave of the pandemic, in early December, the CNB extended the application of the preferential treatment to include also the moratoria granted after 1 October 2020 to clients hit by the COVID-19 pandemic until end-March 2021, with the maximum duration of the moratorium being nine months. A similar approach is also applied to clients affected by the earthquake.

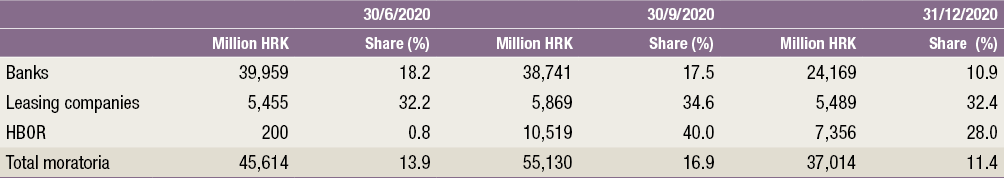

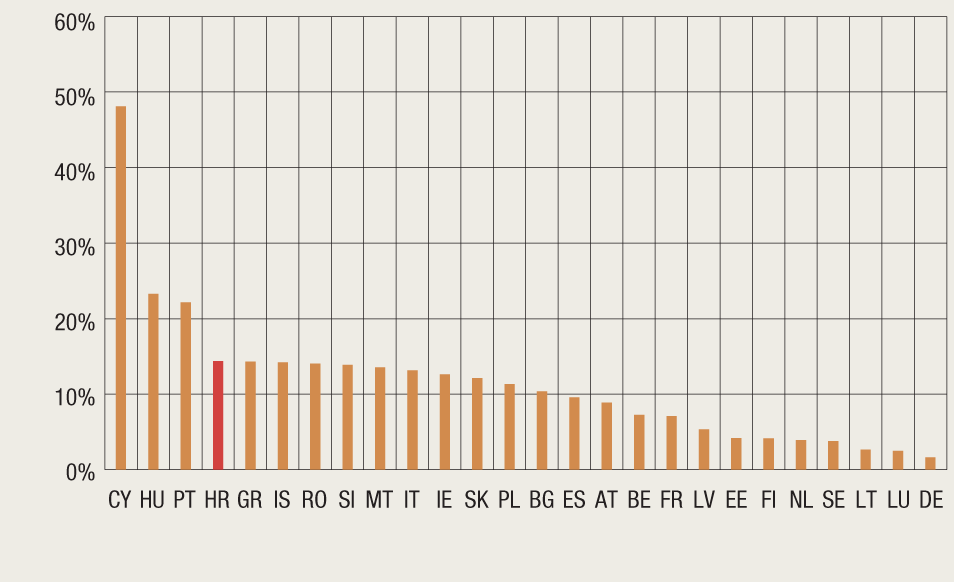

As a result, the banks very soon, in spring 2020, started granting temporary payment deferrals to debtors unable to meet their due loan payment obligations because of the pandemic (Table 2). HBOR and leasing companies acted similarly; HANFA made it possible for them to take a flexible approach to clients affected by the pandemic. According to bank data for end-September, by end-2020 almost two thirds of the moratoria granted to households should have expired; by end-2020 a little below one half of the longer moratoria granted to non-financial corporations should have expired and by end-September 2021 a further 44% of them will expire (probably mostly those granted to debtors in the tourist activity). According to preliminary data for December, at year-end, the moratoria thus covered approximately one tenth of all loans (approximately 17% of corporate loans and a little less than 3% of household loans). It should be noted that in terms of the relative share of the moratoria in total loans, credit institutions in Croatia in mid-2020 were among the top EU member states (Figure 1), suggesting that the pandemic could have a bigger negative impact on bank operations in Croatia than in the rest of Europe.

Table 2 Moratoria on debtors’ obligations to financial institutions

Notes: Data shown are those collected by the CNB from the banks, HBOR and HANFA for the purpose of reporting to the European Systemic Risk Board on public and other support measures during the pandemic. The share (%) shows the share of moratoria in the total value of credit and leasing claims of the shown financial institutions.

Sources: CNB, HANFA and HBOR.

Figure 1 Comparison of the share of COVID-19 moratoria in total household and corporate loans of banks

Notes: Data as at end-June 2020. Due to methodological differences, data for Croatia differ slightly from those collected by the CNB from the banks (Table 2).

Source: European Banking Authority (EBA).

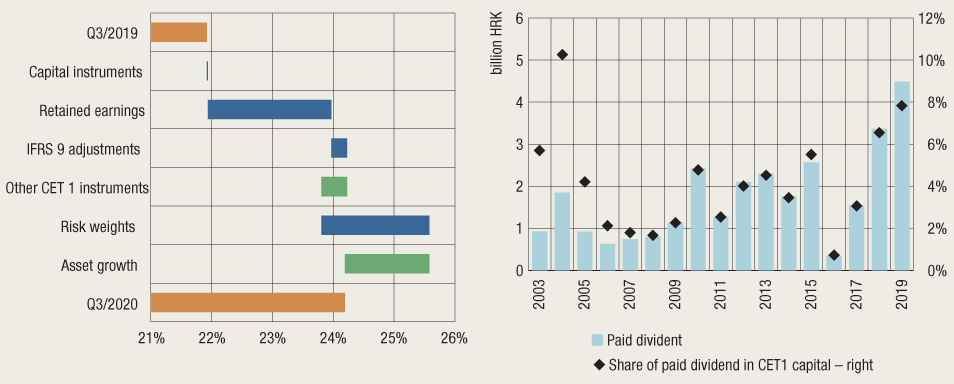

At the time when the coronavirus pandemic struck, the Croatian banking system was highly liquid and well capitalised and the monetary and microprudential policy measures taken supported improved regulatory liquidity and solvency indicators in 2020. The increase in the common equity tier 1 ratio of 2.3 percentage points over a one-year period up to September 2020 (Figure 2) was mostly driven by the CNB’s order on the inclusion in the capital of the profit generated in 2019 (increase of 2.0 p.p.) and the effects of changes in the European regulatory framework, following the adoption of Regulation (EU) 2020/873 (the so-called “quick fix”) towards the end of the second quarter of 2020 (total increase of 1.6 p.p). Of the latter, the re-introduction of the temporary possibility of use of the 0% risk weight for exposures to the Republic of Croatia denominated in euro had the biggest impact, followed by the impact of the possibility of a gradual inclusion of increased provisions for the expected credit risks, which alleviated the earlier negative effects of the use of IFRS 9 on capital. However, the fall in the capital adequacy ratio was fuelled by increased assets following an increase in lending. Had the trend of distribution of almost the entire profit through dividends continued in 2020 (see Figure 2 right and Financial Stability No. 21, Figure 6.27), i.e. had the regulatory changes introduced under the “quick fix” not been introduced, the common equity tier 1 ratio in 2020 would have declined and certainly fallen below 20%.

Figure 2 Increase in the common equity tier 1 ratio in 2020 mirrors regulatory reliefs and the application of the supervisory order on withholding profit

Source: CNB calculation.

What would banks’ business results have been like had it not been for the lenient regulatory treatment of exposures?

Regardless of the worsening of macroeconomic developments, owing to a more lenient regulatory treatment of exposures to clients affected by the pandemic and earthquakes, which postponed the identification of portfolio deterioration, credit institutions in 2020 did not record any significant increase in non-performing loans, except in the segment of cash loans to households (see chapter 1, Figure 4). On the other hand, simulations based on satellite models from the CNB framework for macroeconomic stress testing of credit institutions indicate that unfavourable economic developments would have considerably increased non-performing loans[3], particularly in the corporate sector (Figure 3), had it not been for the favourable regulatory treatment (combined with active measures of support to the economy).

The profit of credit institutions in the first nine months of 2020 halved on an aggregate level from the previous year. This was mostly due to increased costs of impairment and provisions for performing loans with a considerable increase in credit risk (Stage 2) and non-performing cash loans to households as well as a fall in net operating income (lower net interest income and income from dividend of subsidiaries). In the absence of the favourable regulatory treatment of COVID-19 exposures, a bigger amount of loans classified as non-performing in 2020 would have led to bigger impairments and thus to even less favourable business results.

Figure 3 Comparison of developments in the non-performing loan ratio (NPLR) in 2020 with a simulation that excludes the effects of the favourable regulatory treatment and with the global financial crisis

Note: The time period t0 for NPLR and NPLR_covid_excluding measures refers to the first quarter of 2020 and in the case of NPLR_GFC it refers to the fourth quarter of 2008.

Sources: CNB calculation and CBS.

In lieu of a conclusion: the importance of capital preservation amid uncertainties regarding the developments in the health and economic crisis.

Financial stability was maintained in the first year of the crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The full impacts of the crisis cannot be seen yet and there is considerable uncertainty as to the moment when the pandemic will be contained and life return to normal, adapted to the new circumstances.

Until end-March 2021, credit institutions may grant moratoria to orderly clients affected by the pandemic and the earthquake and may classify such moratoria until end-2021 at the latest under more flexible regulatory conditions. Only once we near the end of that period may we expect to get a clearer picture of the actual magnitude of non-performing loans and effects on profitability and possibly bank capitalisation. In addition, the course and intensity of such developments might also depend on the possible cessation of public support, which continues to be an important source of liquidity for some companies, and indirectly their employees, as well as credit institutions. Therefore, the business results of banks will not mirror the actual effects of the pandemic before 2021 and possibly even later, so those relating to the year 2020 should be observed with caution.

All this prompted the Croatian National Bank to adopt on 15 January 2021 a macroprudential Decision on a temporary restriction of distributions (hereinafter: Decision), temporarily restricting in 2021 distributions of dividends, redemption of own shares and award of variable remuneration so as to increase credit institutions’ resilience and maintain the stability of the financial system as a whole. According to preliminary data on halved profits in 2020 compared with the year before, and under the assumption that credit institutions will include the same percentage of retained profit in the capital as in the year before, this Decision should contribute to a 1 p.p. increase in the capital adequacy ratio at system level. Given the Decision’s temporary character, the Croatian National Bank will continue to monitor the factors described in this Box and will, based on the findings of its analysis, adjust the duration of this Decision, i.e. decide on its possible early cancellation or its extension into the following year.

3.2. Transposition of the provisions of CRD V relating to macroprudential activities into the Croatian legislative framework

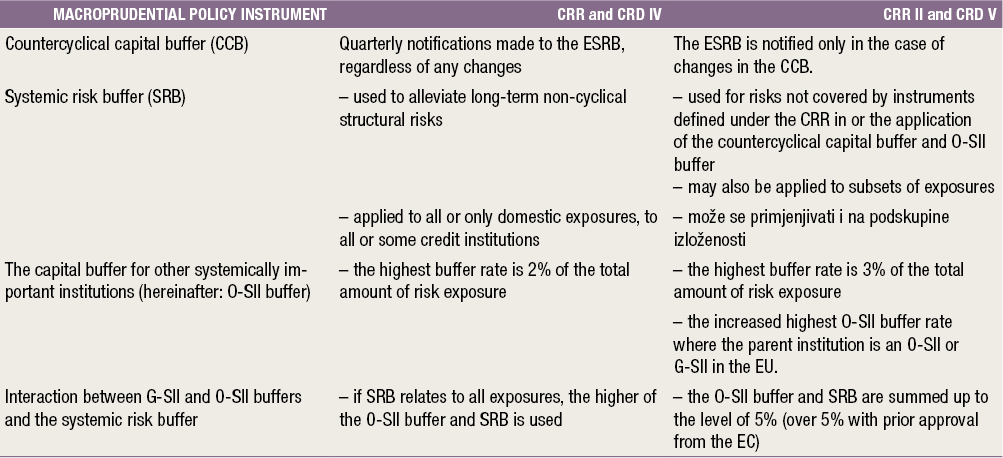

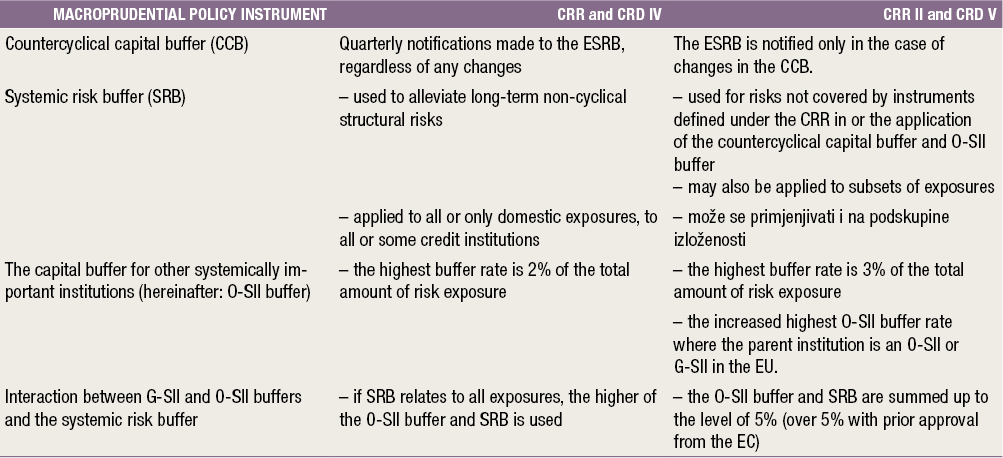

The Act on Amendments to the Credit Institutions Act (hereinafter: AACIA) of December 2020 (OG 146/2020) completes the transposition of the provisions of CRD V into the Croatian legislative framework. The European regulatory framework relating and applying to macroprudential policy is enshrined in Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms – CRD IV and in Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms – CRR[4]. The CRD IV and CRR package has been in force since January 2014, with some provisions entering into force in early 2019. With a view to promoting the implementation of the Basel III standard, an amended package consisting of CRD V and CRR II was adopted that entered into force on 27 June 2019. The transposition of the provisions of CRD V into national legislations was to be completed by 28 December 2020, and in the Republic of Croatia this was done through the AACIA. A summary overview of the most important changes in macroprudential instruments is shown in Table 1.

The biggest changes in the area of macroprudential instruments were made in the part that regulates systemic risk buffer, which, as explicitly prescribed now, may not be used to address the risks covered by the countercyclical capital buffer or the capital buffer for other systemically important credit institutions (hereinafter: O-SIIs). This prevents overlapping in the use of these capital buffers. However, it has been provided that this capital buffer may be used in such a way that, in addition to the general rate, a specific rate may be applied to particular exposures or sectors. In such a case, the sum of the general and individual capital buffers for systemic risk will represent the total, or combined systemic risk buffer. There are four main categories of exposures by sectors: 1) exposures to natural persons secured by residential real estate; 2) exposures to legal persons secured by commercial real estate; 3) all exposures to legal persons except those referred to in item 2); 4) all exposures to natural persons except those referred to in item 1); with further divisions to sub-sectoral exposures possible. In this context, the European Banking Authority issued in early October 2020 the Guidelines on the appropriate subsets of sectoral exposures to which competent or designated authorities may apply a systemic risk buffer in accordance with Article 133(5)(f) of Directive 2013/36/EU further regulating the application of the systemic risk buffer to subsets of sectoral exposures. Three dimensions of exposures may be employed: type of debtor or counterparty sector, type of exposure and type of collateral. In addition, the relevant authorities may supplement these dimensions with three sub-dimensions: economic activity (for the “legal person” element of the dimension “type of debtor or counterparty sector”), risk profile (for the dimension “type of exposure”) and geographical area (for the dimension “type of collateral”). A pre-condition when defining a subset of sectoral exposures in the application of a sectoral SRB is the systemic relevance of the risks stemming from these exposures. The Guidelines also regulate the issue of the

interaction between the sectoral systemic risk buffer and other macroprudential measures and reciprocity.

Table 1 Changes in macroprudential policy instruments of the harmonised European legislation

Source: CNB.

As regards the O-SII buffer, a higher rate may be used. Thus the maximum permitted rate of this buffer is increased from 2% to 3% of the total amount of risk exposure. The restriction on the rate that may be applied to those credit institutions whose parent institution is an O-SII or a global systemically important institution (hereinafter: G-SII) in the European Union has been lifted. Before the AACIA entered into force, an O-SII whose parent institution is an O-SII or a G-SII in the EU on a consolidated level, had to maintain only the capital buffer rate determined for the parent institution, or 1% if that rate was below 1%. Under the new legislative framework, this restriction was raised to the lower of the rate of the parent institution increased by 1 percentage point and 3%.

A significant change is that the O-SII buffer and the systemic risk buffer will be additive. Namely, these buffers used to be additive only in a case in which the systemic risk buffer was applied exclusively to domestic exposures (in other cases the higher of the two buffer rates was used). Under this new arrangement, if a credit institution is subject to an O-SII buffer, this buffer is added to the systemic risk buffer.

Changes to the countercyclical capital buffer were the smallest and only involve the system of ESRB notification, which will, under this new arrangement, be notified only in the case of a change in this buffer instead of after each quarterly review, which was the practice previously.

3.3. Decision on the application of the systemic risk buffer

In December 2020, the Croatian National Bank issued a new Decision on the application of the systemic risk buffer, prescribing that all credit institutions with a head office in the Republic of Croatia should maintain a systemic risk buffer of 1.5% of the total risk exposure. As of the entry into force of this Decision (OG 144/2020), the different buffer rates of 1.5% and 3.0% cease to apply to the two groups of credit institutions, depending on the type, scope and complexity of their operations.

The Decision on the systemic risk buffer is based on an analysis of the structural elements of financial stability and systemic risks in the economy, which determined a further increase in structural vulnerabilities of the system and exposures to systemic risk following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, this analysis also determined that there was no more need for systemic risks stemming from the size and complexity of individual credit institutions and banking sector concentration to be covered by a higher systemic risk buffer rate since, under the new regulatory framework, they are covered by the O-SII buffer that is in now in use. To avoid the overlapping of systemic risks that are covered by these buffers, while taking into account the important role that the banking sector plays in supporting faster economic recovery through continued lending, the Croatian National Bank has decided to even out the systemic risk buffer at the lower of the two previously used levels, which is equal to 1.5% of the total amount of risk exposure for all credit institutions.

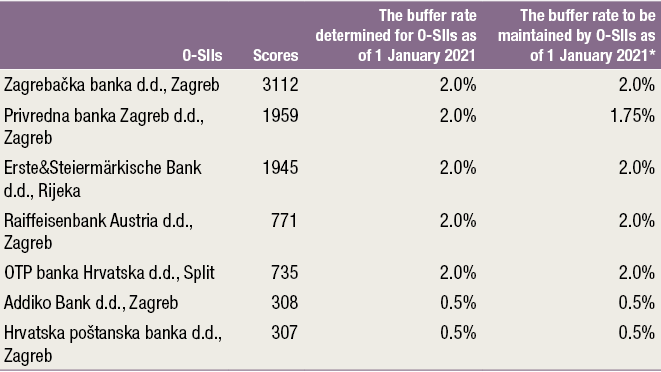

3.4. Review of the systemic importance of credit institutions

In the fourth quarter of 2020, the CNB conducted a regular identification of O-SIIs in the Republic of Croatia and determination of the capital buffer rates for the identified O-SIIs. The process of identification was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines of the European Banking Authority (EBA/GL/2014/10, hereinafter: Guidelines) and Article 138 of the Credit Institutions Act (OG 159/2013, 19/2015, 102/2015, 15/2018, 70/2019, 47/ 2020 and 146/2020) in compliance with the internal methodology and as in the previous classifications, a standard scoring approach was used with the threshold being reduced discretionarily to 275 basis points. Seven O-SIIs were identified in the process. To determine the capital buffer rate for O-SIIs, the results of the method of equal expected impact were used, as one of the methods recommended in the ESRB handbook on operationalising macroprudential policy in the banking sector. The buffer rates determined for O-SIIs are shown in Table 2. The results of the annual review were published in December 2020 on the website of the Croatian National Bank.

Table 2 Identified O-SIIs and O-SII buffer rates

* Taking into account the status of the parent O-SII or G-SII in the EU, where applicable.

Source: CNB.

3.5. Continued application of the countercyclical capital buffer rate for the Republic of Croatia in the first quarter of 2022

In December 2020, the Croatian National Bank carried out a regular quarterly assessment of the required level of countercyclical capital buffer. Taking into account the need to ensure continuity of bank lending to the non-financial private sector amid worsening of economic developments caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the countercyclical buffer rate to be applied from 1 January 2022, will remain 0%.

3.6. Combined capital buffer

The described changes in individual capital buffers led to a change in the level of the combined capital buffer for O-SIIs. As of the date of entry into force of the AACIA, the combined capital buffer is the sum of the capital conservation buffer, countercyclical capital buffer, systemic risk buffer and the buffer for other systemically important institutions. Thus, as of 1 January 2021, O-SIIs will maintain a combined capital buffer of between 4.5% and 6% of the total amount of risk exposure, having increased by 0.25 p.p. (for one bank, due to the restriction stemming from the O-SII buffer rate of the parent institution), and 0.5 p.p. (for all other O-SII banks). Credit institutions that are not O-SIIs, will maintain a combined buffer at the same level as previously, i.e. at 4% of the total amount of risk exposure.

3.7. Recommendations of the European Systemic Risk Board

3.7.1. Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board amending Recommendation ESRB/2020/7 on restriction of distributions during the COVID-19 pandemic(ESRB/2020/15)

The European Systemic Risk Board issued in December 2020 a Recommendation (ESRB/2020/15), extending the duration of the Recommendation on restriction of distributions during the COVID-19 pandemic, issued in May, in a somewhat changed format. Under this Recommendation relevant authorities are asked to request financial institutions under their supervisory remit to refrain until 30 September 2021 from making a dividend distribution or giving an irrevocable commitment to make a dividend distribution, buying-back ordinary shares, and creating an obligation to pay variable remuneration to employees whose professional activities have a material impact on an institution's risk profile. The aim of this Recommendation is to prevent a reduction in the quantity or quality of own funds of financial institutions so as to avoid threats to financial stability amid the crisis and prevent a slowdown in economic recovery. The Recommendation is applied at EU group level (or at an individual level where a financial institution is not part of an EU group), and where appropriate, at a sub-consolidated or individual level. The ESRB is aware of the importance that raising capital externally plays for some credit institutions, and the importance that the policy of distributions plays in the process, and has thus provided in the Recommendation for distributions that do not exceed the conservative threshold set by the competent supervisor, in direct communication with the credit institution.

3.7.2. Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board regarding the Norwegian notification of its intention to set a systemic risk buffer rate in accordance with Article 133 of Directive (EU) 2013/36/EU (ESRB/2020/14)

In accordance with Article 133, paragraph (14) of Directive 2013/36/EU, the European Systemic Risk Board issued in December 2020 a Recommendation that the introduction of a SyRB rate of 4.5% in Norway is considered justified, suitable, proportionate, effective and efficient for the risk targeted by the Norwegian competent authority and that none of the existing measures is sufficient to address these risks.[5] The single systemic risk buffer rate of 4.5% applies to the domestic exposures of all credit institutions authorised in Norway, including the subsidiaries of parents established in another European Economic Area (EEA) country. The introduction of this rate cancels the application of two different systemic risk buffer rates applied to two groups of credit institutions; the 5% rate applied to O-SIIs and the 3% rate applied to all other credit institutions, while at the same time, O-SIIs will apply separately determined buffer rates for O-SIIs.

3.7.3. Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board on identifying legal entities (ESRB/2020/12)

With a view to further promoting the use of a global legal entity identifier (LEI) for all parties to financial transactions, the European Systemic Risk Board issued in November 2020 a Recommendation on identifying legal entities (ESRB/2020/12). The purpose of this Recommendation is to contribute, in line with the ESRB’s mandate, to the prevention and mitigation of systemic risks to financial stability in the Union through the establishment of systematic use of the LEI[6] by entities engaged in financial transactions. To achieve this objective, this Recommendation seeks the introduction of a Union legal framework to uniquely identify legal entities engaged in financial transactions by LEIs and to make the use of the LEI more systematic in respect of supervisory reporting and public disclosure. The Recommendation provides for the use of the principle of proportionality under which smaller entities that do not form part of a wider group would be exempt from the requirement to obtain an LEI, or require that they be provided with an LEI at no cost. Taking into account the time frame for the adoption of such a Union framework, the ESRB recommends that relevant authorities pursue and systematise their efforts to promote the adoption and use of the LEI, making use for this purpose of the various

regulatory or supervisory powers which they have been granted under national or Union law.

3.8. Macroprudential policy implementation in other European Economic Area countries

Following the relaxation of the countercyclical buffer rate in many European Economic Area countries in the wake of the outbreak of the pandemic, the fourth quarter of 2020 did not see further easing of this buffer requirement. In September 2020, Hungary lifted the preventive tighter measures aimed at maintaining stable financing in foreign currency and reducing the risk of currency mismatches introduced in March 2020 in response to the outbreak of the pandemic, thus returning them to the state prior to the changes of that month.

By contrast, some countries started reintroducing or extending the application of tighter macroprudential measures. Thus in January 2021, Luxembourg introduced the previously announced increase in the countercyclical capital buffer from 0.25% to 0.5%, concurrently introducing the obligatory application of the loan-to-value ratio for loans secured by residential real estate in that country. The Norwegian competent authority adopted the previously mentioned decision on the systemic risk buffer of 4.5% for domestic exposures for all credit institutions authorised in Norway. Sweden and Belgium extended the application of tighter temporary measures under Article 458 of the Regulation on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms relating to the application of stricter risk weights for loans secured by a lien on real estate for banks using the IRB approach to calculate minimum capital requirements for credit risk.

Table 3 Overview of macroprudential measures applied in EU member states, Iceland and Norway

Note: The listed measures are in line with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (CRR) and Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (CRD IV). The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication. Green indicates measures that have been added since the last version of the table. Light red indicates measures that countries have released in response to the crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic.

Disclaimer: of which the CNB is aware.

Sources: ESRB, CNB and notifications from central banks and websites of central banks as at 7 January 2021.

For details, see: https://www.esrb.europa.eu/national_policy/html/index.en.html and https://www.esrb.europa.eu/home/coronavirus/html/index.en.html.

Table 4 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

Note: The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication. Green indicates measures that have been added since the last issue of Macroprudential Diagnostics.

Source: CNB.

Source: Građevinar, No. 10, 2020 (http://www.casopis-gradjevinar.hr/arhiva/issue/272) ↑

European Economic Forecast, Autumn forecast, November 2020 ↑

The projections used in the simulation are CNB’s December 2020 Monetary projections published in Macroeconomic Developments and Outlook No. 9). The models will be described in the publication Financial Stability No. 22 that will be published in May 2021. ↑

In its original form, a regulation is a binding legislative act applied directly by member states while a directive is a legislative act that sets out a goal that must be achieved and it is up to the individual countries to devise the transposition of directives into national legislation. ↑

When a systemic risk buffer rate is set between 3% and 5% and when one subset of the financial sector is a subsidiary whose parent is established in another member state, pursuant to Article 133, paragraph (14) of Directive 2013/36/EU, the competent authority or the designated authority notifies the authorities of that member state, the European Commission and the ESRB. Within one month of the notification, the EC and the ESRB will issue a recommendation on the measures taken in accordance with this paragraph. ↑

Legal entity identifier (LEI) means a reference code to uniquely identify legally distinct entities in a global database. ↑