Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 16

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected, according to calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of events that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to the structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1. Identification of systemic risks

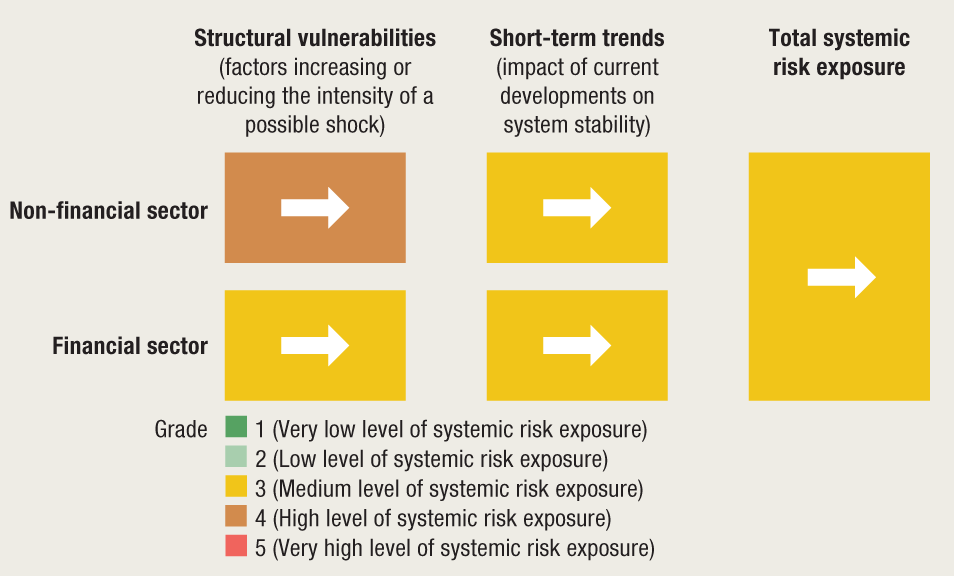

Total systemic risk exposure at the end of the fourth quarter of 2021 remained moderate (Figure 1). Economic activity recovered more rapidly and strongly than expected, so that businesses relied less on fiscal support. However, risks are still elevated due to uncertainties regarding the end of the pandemic, growing consumer price inflation, strong residential real estate price growth and increasing geopolitical risks. Therefore, the degree of exposure to systemic risks has remained unchanged for all sectors from the previous assessment (Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 15).

Figure 1 Risk map, fourth quarter of 2021

Note: The arrows indicate changes from the Risk map in the third quarter of 2021 published in Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 15 (September 2021).

Source: CNB.

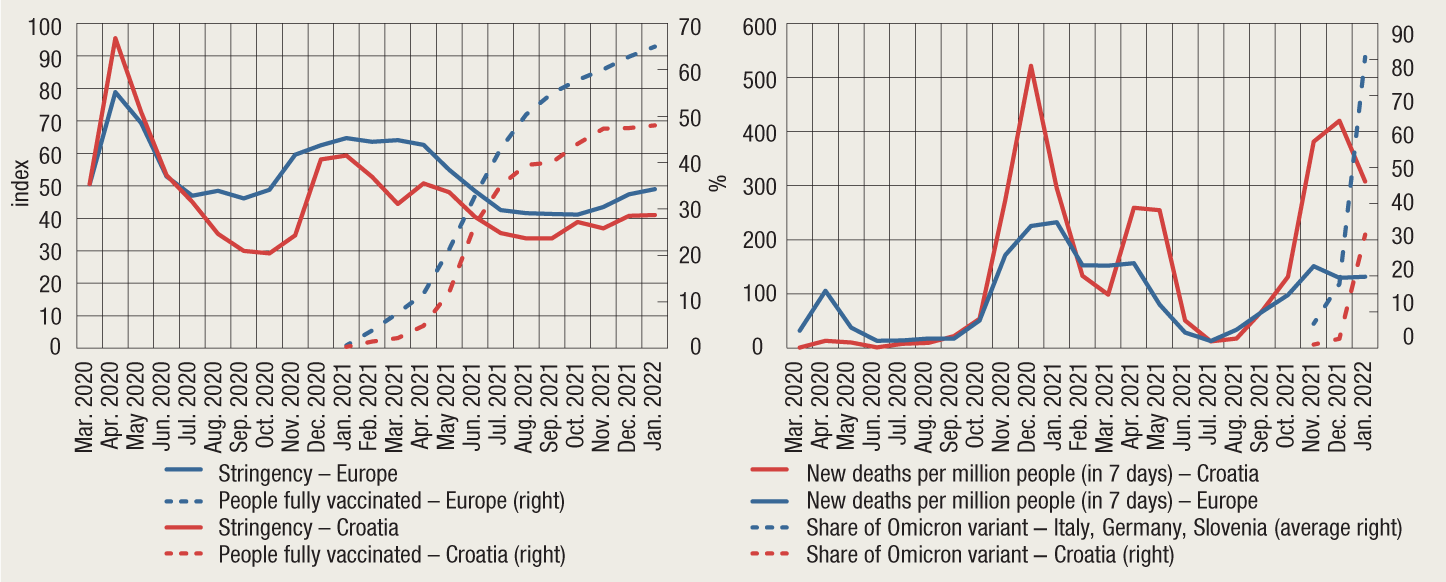

The gradually increasing vaccination rate, adjustment to coexistence with the virus and more relaxed epidemiological measures than in 2020 contributed to the recovery of domestic and foreign demand, good tourism results and the generally strong economic growth. However, towards the end of 2021, the highly contagious Omicron variant of the coronavirus appeared, causing most European countries to once again adopt tighter epidemiological measures. According to available indicators, domestic economic activity increased in the last quarter despite the new pandemic wave. Still, there has been a noticeable slowdown in the rate of recovery. Consumer sentiment deteriorated slightly, as did business expectations in industry and services. Pronounced uncertainty regarding the future course of the pandemic remains the main risk for economic activity (Figure 2).

Figure 2 COVID-19 in Croatia and the EU: epidemiological stringency and vaccination rate (left panel) and deaths and Omicron variant share (right panel)

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Data on deaths and vaccination rates from the end of January 2022.

The strong growth in real GDP in 2021 (according to CNB Macroeconomic Developments and Outlook No. 11, GDP is expected to have grown by 10.8%) was spurred by all components of demand, most notably the recovery in tourism revenues. Still, whereas tourism revenues could stay below pre-pandemic levels, real GDP and other components of demand could well reach levels higher than those recorded in 2019. The increase in tax revenues (primarily VAT) supported by economic growth coincided with reduced expenditures associated with measures aimed at mitigating the economic consequences of the pandemic, which, combined, produced a favourable effect on the general government budget. The increase in net exports of services and stronger absorption of EU funds contributed to the increase in the current and capital account surplus.

Revenues of enterprises recovered strongly in 2021. Tax Administration data indicate that in 2021, the amount of fiscalised receipts grew by some 25% from 2020 and around 3.5% from 2019. Nevertheless, revenues of activities requiring social contact (accommodation, food service activities, passenger transport and other service activities) still have not returned to pre-crisis levels (see Box 1 Recovery of the performance of non-financial corporations in 2021). In line with stronger business activity, corporate demographics gradually returned to normal in 2021, so that the rate of corporations that discontinued regular business, after having decreased sharply upon the onset of the pandemic, increased and returned to average levels recorded in the period between 2017 and 2019. Operations of corporations are still hampered by disruptions in the supply chains of finished products and production materials (Figure 6, left panel) and the inflation of supplier prices and transportation costs. Furthermore, the Omicron variant of the coronavirus has been causing significant organisational difficulties in corporations’ daily operations.

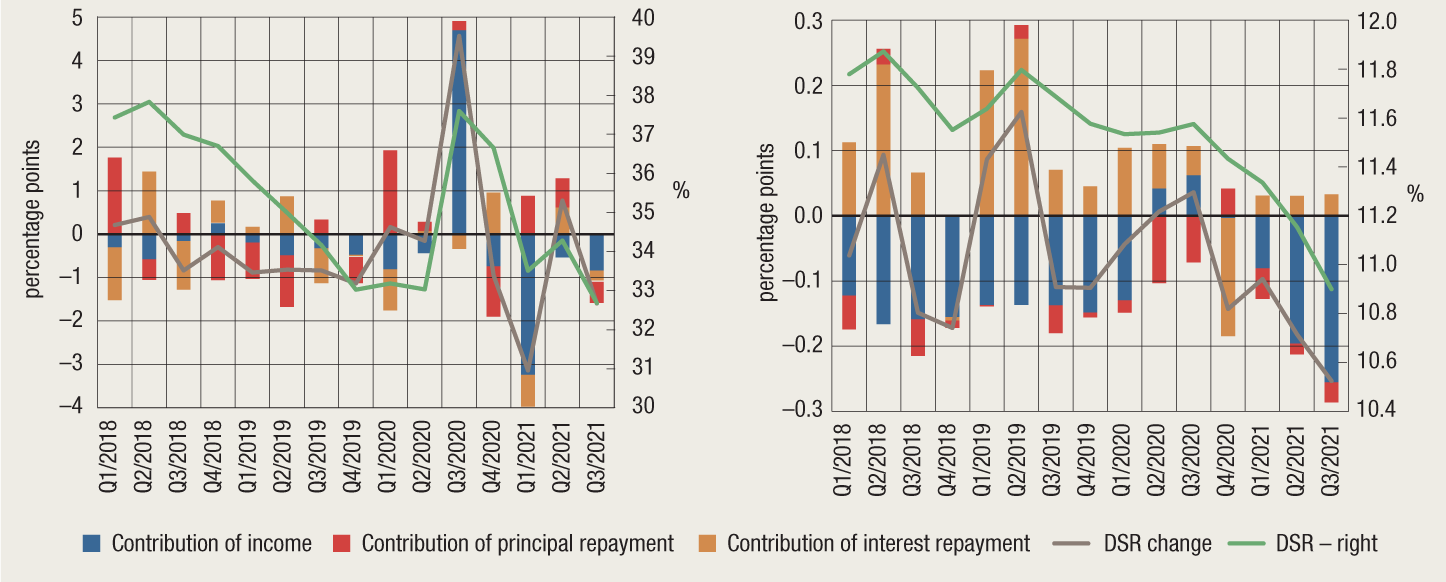

Increased revenues coupled with the still favourable financing conditions made debt servicing of non-financial corporations easier. However, the sensitivity of the corporate debt servicing burden, as measured by the ratio of principal and interest repayment to income, to the changes in macroeconomic developments is reflected in the strong change in the aforementioned ratio seen in the first year of the pandemic (Figure 3, left panel and Box 1). Due to the sharp fall in revenues occurring at the time, the fixed cost burden increased, causing the gross disposable surplus to shrink, particularly in activities most heavily affected (accommodation, food services, passenger transport), leading to a rapid increase in the repayment burden. The burden was alleviated by the fast intervention of economic policy makers.

The recovery of aggregate solvency indicators and household sector liquidity was coupled with relatively mild lending standards in a significant portion of new loans. The continued downward trend in the debt-to-financial assets ratio suggests that household solvency risk decreased further from an already relatively low level. The slight increase in total income and the continued decline in interest rates seen during the pandemic enabled the repayment burden to decrease further despite growing household debt (Figure 3, right panel). Household debt is increasing due to the strong growth in housing loans, which increased by around 10% in 2021, but also on account of the recovering demand for general-purpose loans. Around one half of consumer loans are granted to consumers with a debt service-to-income ratio higher than 40%, which, according to results of empirical research, may suggest an elevated risk of irrecoverability. Consumers with higher debt indicators are particularly exposed to the risk of difficult debt servicing in case of an unfavourable income shock or an increase in interest rates (Shamloo et al., 2019).[1]

Figure 3 Debt service-to-income ratio developments in the corporate (left panel) and the household (right panel) sector

Notes: DSR means debt service ratio. The methodology of calculation is based on BIS methodology: https://www.bis.org/statistics/dsr.htm. In the corporate sector, income means gross operating surplus, and in the household sector, it means disposable income.

Sources: CNB, CBS and Tax Administration.

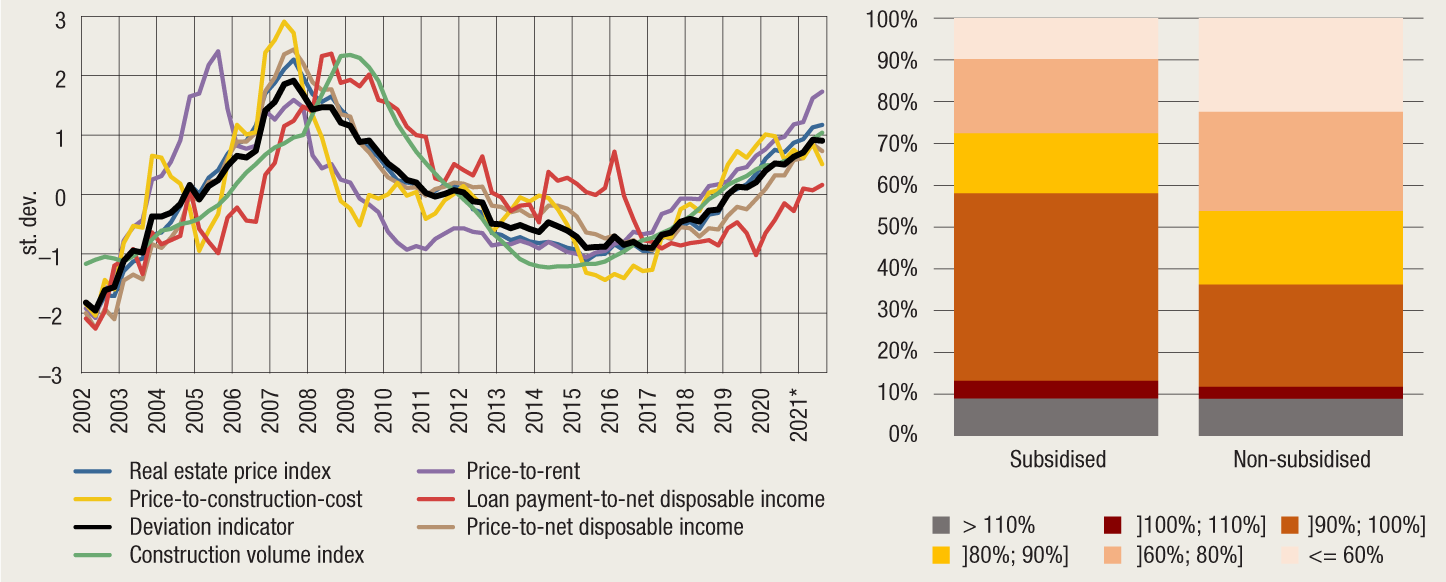

Strong housing lending is linked to growing residential real estate prices, which have been increasingly deviating from the long-term equilibrium level (Figure 4, left panel). After residential real estate prices increased by 5.8% in the first half of 2021 from the same period in the preceding year, in the third quarter of 2021, their growth picked up to 9.0% under the influence of strong demand and increased costs of construction. Consequently, over the last five years, prices of residential real estate grew by around 40%. Having grown at a faster pace than income, their affordability continued to deteriorate, and the high level of prices and their fast growth relative to long-term trends expose buyers and credit institutions to revaluation risk. Following a slight decline in the first year of the pandemic, the number of purchase and sale transactions in the residential real estate market recovered in 2021. Furthermore, real estate market activity increased due to strong demand coming from non-residents, triggered by negative interest rates in euro area countries, and also, possibly, the possibility of remote work from Croatia.

Lending activity and real estate market are still significantly affected by the government’s housing loans subsidy programme. The new round of subsidies expected in spring 2022 could support continued growth in both housing loans and prices. Subsidised loans have lower repayment burden in the initial repayment period, lowering credit risk in that period. However, if debtors cease to repay the loan in later years, due to the elevated ratio of loan amount to pledged real estate value, banks are exposed to slightly higher potential losses than with other housing loans (Figure 4, right panel).

Figure 4 Deviation of the residential real estate market indicator from the long-term equilibrium (left panel) and the distribution of the principal in newly-granted housing loans according to classes of the loan-to-value ratio (LTV) (right panel)

Notes: The figure shows cyclical components of various sub-indicators relevant for developments in real estate prices obtained using the Hodrick-Prescott filter (λ = 400 000), included in the composite indicator. The indicator is calculated as the first main component of standardised sub-indicator cycles. The volume of construction works refers to housing construction (left). The LTV ratio refers to housing loans disbursed in the period from November 2020 to October 2021 (right). Verification of data on lending conditions is still ongoing.

Sources: CBS, Tax Administration and Eurostat (CNB calculation (left)) and Decision on collecting data on standards on lending to consumers (right).

Loan quality continued to improve in the third quarter of 2021, supporting the increase in profitability and the capitalisation of credit institutions. Fast economic recovery and an ample government support package enabled enterprises to bridge the period until their operations returned to normal and to exit moratoria without significant difficulties. With the exception of activities most heavily affected by the pandemic (accommodation, food services and transportation), in which the share of non-performing loans continued to grow, the quality of all loan portfolio parts improved and charges for value adjustments went down. The improvement in the loan portfolio quality was also supported by the revival of the bad loan market in 2021. On the other hand, an additional increase in the already high share of liquid assets coupled with continued downward interest rate trends reduced the net interest margin and limited the recovery of profitability, so that at the end of 2021, ROAA and ROAE stood at 1.3% and 8.3% respectively, still below pre-pandemic levels. Total capital ratio stood at 25.6% at the end of September 2021, the same as at the end of 2020 and 2.4 percentage points above the level recorded at the end of 2019.

Although the developments in the financial markets in Croatia and abroad were favourable by the end of 2021, the beginning of the current year calls for caution. Anticipations of a sooner normalisation of the Fed’s monetary policy pushed US equity indices sharply downwards, with the most significant drop in value seen in cryptoassets, technology firms operating at a loss and in risk capital instruments. Following a strong increase in December, which helped offset losses recorded during the pandemic, the Croatian equity index CROBEX went down again in early 2022.

Box 1 Recovery of the performance of non-financial corporations in 2021

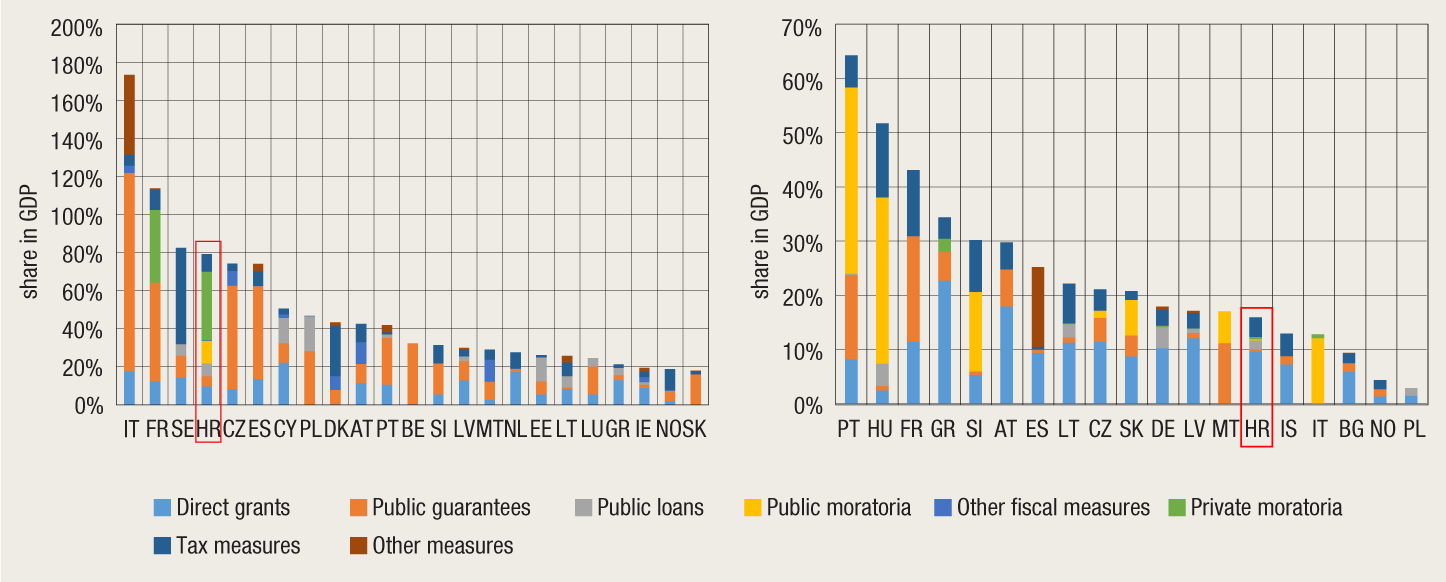

The drop in the business activity of non-financial corporations in Croatia in 2020 was a brief, but exceptionally strong shock. Considering the intensity of the shock, which depended on the stringency of measures, but also on the structure of the economy, economic policy makers in Croatia responded fast, offering ample support by introducing and initiating a wide range of measures (fiscal, supervisory and monetary), which resulted in Croatia ranking among the first four EU countries according to the ratio of total allocated economic aid to GDP (Figure 1). In 2021, most measures expired, or their application was minimised. At the end of the third quarter of 2021, there were virtually no active moratoria or public guarantees, and loans to preserve liquidity were being gradually repaid, making Croatia one of the countries that had a relatively small number of actively applied measures.

Figure 1 Economic aid amount in the EU from the beginning of the pandemic to September 2021 (left panel) and the balance of outstanding credit support measures in the EU as at 30 September 2021 (right panel)

Notes: Allocated funds refer to planned economic aid, while the maximum total amount of aid granted since the measure came into effect is shown for measures whose budgets were not planned in advance. The figure shows only the public loans granted to finance additional liquidity, while private loans to finance additional liquidity are not covered by the ESRB statistics. Only the countries with a share of measures in GDP above >1% are shown.

Sources: ESRB and CNB.

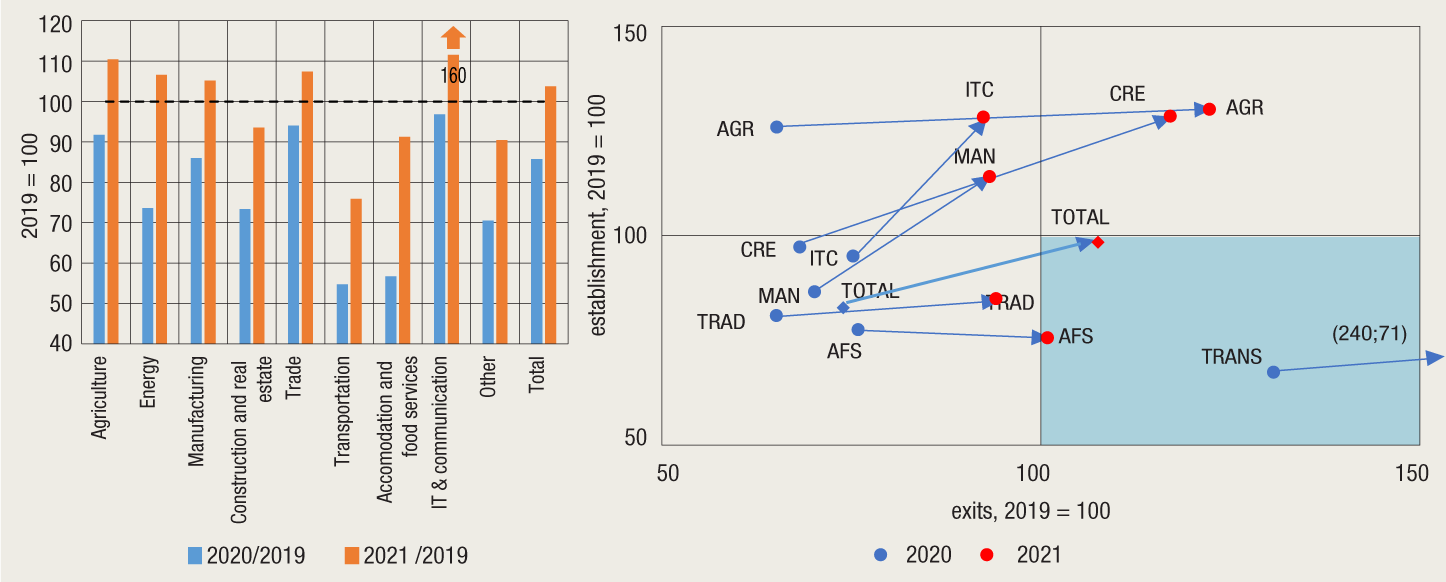

Thanks to the aid package, as well as to the rapid economic recovery, the non-financial corporate sector preserved its profitability, capital, labour force and tangible and intangible assets to a significant extent. Nevertheless, in the same way as the shock, the recovery was asymmetrical, as confirmed by the trends in revenues broken down by activities in 2021 (Figure 2, left panel) and the changes in corporate demographics. As a result, disruptions still exist in the operations of companies engaging in accommodation, food services, passenger transport and other service activities requiring social contact. The aforementioned activities still have not reached the revenue levels recorded in 2019 despite the strong recovery.

Figure 2 Fiscalised receipts (left panel) and exits of firms from the market

Notes: EN: Energy; CRE: Construction and real estate, ITC: IT & communication; AGR: Agriculture; MAN: Manufacturing; TRANS: Transportation; TRAD: Trade; AFS: Accommodation and food services; TOTAL: Non-financial corporations total. Exits mean pre-bankruptcy, bankruptcy and winding-up proceedings including voluntary dissolution without liquidation.

Sources: Tax Administration (left panel); Commercial Court Registry (left panel) and CNB.

Despite the expectations that the pandemic would cause firms to exit the market, this did not happen initially (Figure 2, right panel). Fiscal support, support to liquidity and other measures of aid, such as the temporary suspension of bankruptcy proceedings, temporarily slowed down exits from the market. Furthermore, due to the consequences of the earthquake that struck Zagreb in March 2020, the work of courts was temporarily suspended until necessary check-ups of building stability and the required reconstruction work were performed.

In 2021, market structure dynamics increased and rates of exit from the market returned to their average levels (2017-2019), with certain changes to its structure. At the end of 2020 and in 2021, voluntary exits from the market increased, but it was not until mid-2021 that the number of bankruptcy proceedings returned to pre-pandemic levels, while the number of winding-up proceedings is still below its long-term average. As the establishment of new firms is slower, the average firm is older than in the pre-pandemic period.

Hence, measures adopted in 2020 and 2021 aimed at assisting companies in mitigating the consequences of the pandemic and continuing their operations slowed down the “creative destruction”, i.e. they helped some companies that had little prospect of surviving to linger on the market. To facilitate the process of establishing new firms and to enable an early prevention of unwanted forced exits from the market, the Government of Croatia adopted a new proposal of amendments to the Bankruptcy Act and other legislation in December 2021. The main novelty is the proactive approach whereby financial instability is identified at an early stage and internal restructuring of risky business entities is initiated with the goal of minimising risk materialisation and reducing the likelihood of an unfavourable default scenario leading to bankruptcy and winding-up proceedings.

2. Potential risk materialisation triggers

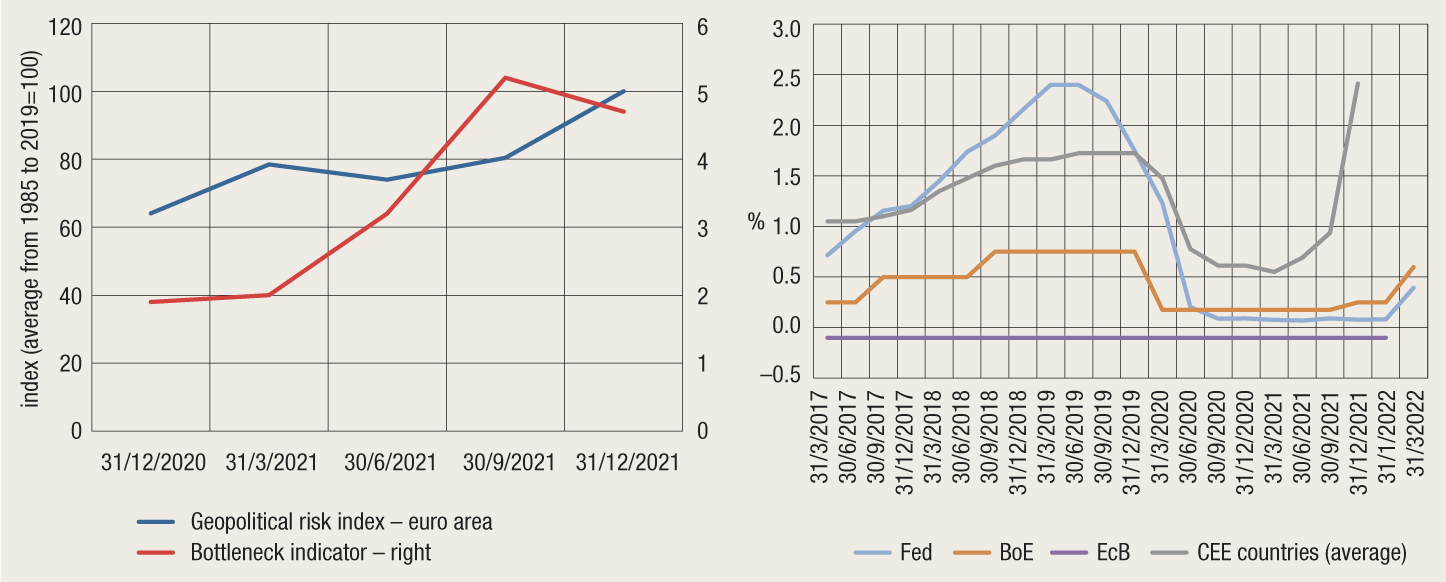

The appearance of the highly contagious Omicron variant of the coronavirus hampered the implementation of “zero-covid policy” in several Asian countries having key significance for world trade (China, Hong Kong, Taiwan) and thus further aggravated the problems in global supply chains. Global supply chain bottlenecks, combined with a deficit in inputs of raw materials and consumables and labour shortages have had negative effects on the supply of goods and have exerted upward pressures on prices, thus slowing down the rebound of the global economy (Figure 6, left panel).

Current geopolitical tensions could push the prices of energy and raw materials, as well as risk premiums, further up. Aggravated relations between Russian and the Ukraine are leading to increased uncertainty, which could result in additional hikes in the prices of energy (oil and gas) and food (cereals and wheat), i.e. increase inflation further. Such trends could spur demand for safe investments and trigger capital outflows from emerging markets. Furthermore, the continued trade tensions between Europe and China and the USA and China may increase the costs of international trade even more and reduce the volume of global trade and financial flows.

Increased inflationary pressures could motivate central banks to a faster and sharper change of course in monetary policy than currently anticipated (Figure 6, right panel). The prolonged period of accommodative monetary policy and the maintenance of exceptionally low, even negative interest rates contributed to the increase in the prices of various forms of assets. Although interest rates are expected to increase gradually for now, faster inflation could trigger sharper turns in the policies of central banks. Interest rate increases that could lead to increasing debt repayment burdens would have a particularly strong effect on countries in which corporate and household debt grew during the pandemic.

The increasing overvaluation of residential real estate increases the risk of a decline in their prices in the event of an unfavourable macroeconomic scenario, which would result in other shocks for debtors and credit institutions as well. The strong growth in housing lending coupled with relatively lax lending conditions point to elevated risks taken on by consumers and credit institutions in granting loans collateralised by residential real estate (see chapter 3 Recent macroprudential activities). Even though aggregate indicators of household debt repayment burden are relatively favourable, growing debt combined with the anticipated interest rate increase could push them upwards. Moreover, subsidies to the beneficiaries of subsidised loans from the first cycle of the government housing loans subsidy programme implemented in 2017 are set to expire this year, which will significantly increase their repayment costs and vulnerability to possible unfavourable shocks stemming from the macroeconomic environment.

The European Green Deal could increase inflation further. Since green policies include measures and policies that may result in temporary price increases (closing down nuclear power plants, investing in new technologies, CO2 taxation), its implementation may permanently raise inflation and thus affect interest rates and other macroeconomic indicators.

Figure 5 Delivery times indices and the geopolitical risk index (left panel) and interest rates (right panel)

Notes: The geopolitical risk index shows the average value of the daily geopolitical threat index over the last thirty days. The bottleneck index shows the effect of supply bottlenecks (in terms of longer delivery times) on inflation in the segment of industrial goods (excluding energy) in the euro area.

Sources: Geopolitical risk index: Caldara, D. and M. Iacoviello (2021), Measuring Geopolitical Risk, working paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, November, data accessed on 21 Feb 2022 at https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.html. Bottleneck indicators: ECB: Bottlenecks and monetary policy, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2022/html/ecb.blog220210~1590dd90d6.en.html. Interest rates: BIS (values until end-2021) and Bloomberg (the average of expected deposit interest rates of central banks as at 11 Feb 2022 and the upper bound of the Fed’s target range).

3. Recent macroprudential activities

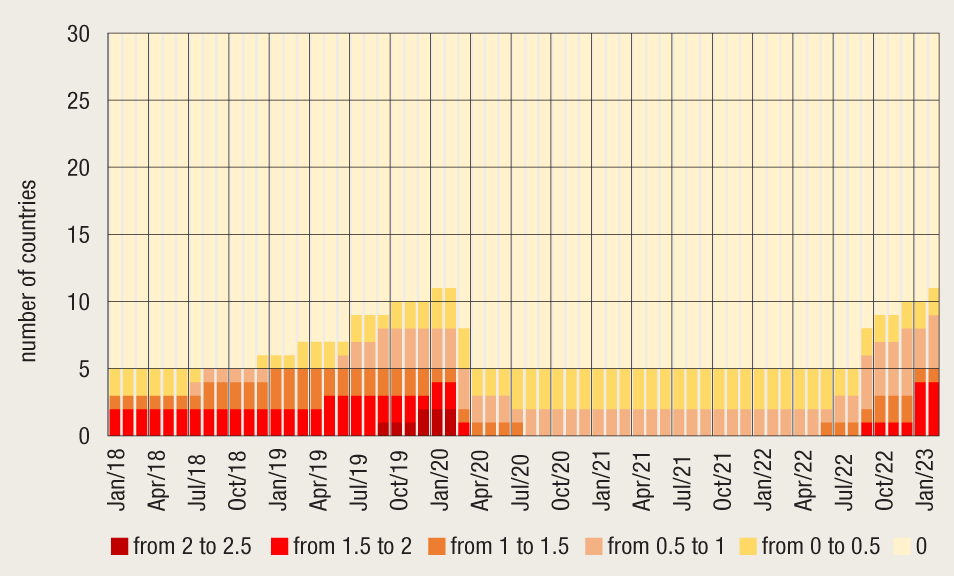

3.1. Announced increase of the countercyclical capital buffer rate for the Republic of Croatia in the second quarter of 2023

In early February 2022, the Croatian National Bank submitted for public consultation the Draft decision on the increase of the countercyclical capital buffer rate for the Republic of Croatia to 0.5%, to be applied as of the end of the first quarter of 2023. The rate is to be raised in response to the accumulation of cyclical systemic risks amid economic recovery following the crisis caused by the pandemic, in particular to the growth in the prices of residential real estate and the pickup in lending activity in the housing loans segment (see chapter 1 Identification of systemic risks). The decision on the required rate has been made according to the relevant indicators of cyclical systemic risk specific for Croatia, based on a new methodology for identifying benchmark countercyclical capital buffer rates (see Box 2 Improvements in the methodology of countercyclical capital buffer identification and calibration in Croatia). As the designated authority, the CNB will continue to monitor regularly the economic and financial developments and the further evolution of systemic risks, so as to be able to adjust in time the countercyclical capital buffer rate.

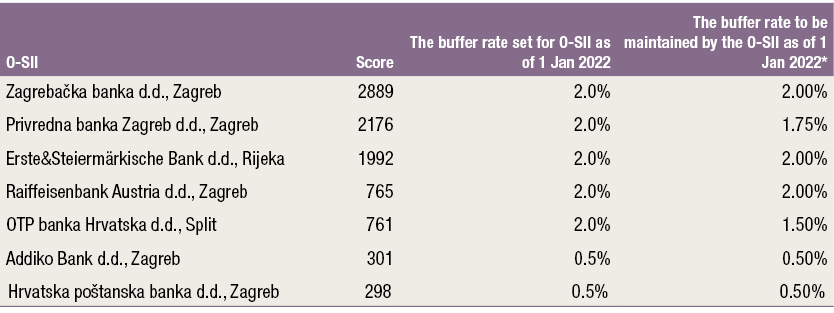

3.2. Review of the systemic importance of credit institutions

In the course of regular identification of other systemically important credit institutions (O-SIIs) in Croatia, performed in the fourth quarter of 2021, seven O-SIIs were identified and their respective capital buffer rates were determined. The process of identification was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines of the European Banking Authority and Article 138 of the Credit Institutions Act (Official Gazette 159/2013, 19/2015, 102/2015, 15/2018, 70/2019, 47/ 2020 and 146/2020, hereinafter ‘the Act’) in compliance with the internal methodology. The Croatian National Bank applied the standard scoring approach for the assessment of O-SIIs, using the so-called mandatory indicators in the four areas (criteria) referred to in Article 138 of the Act available on 31 December 2020 (revised data for all authorised credit institutions having a head office in the Republic of Croatia at the moment of scoring), the adjusted threshold of 275 basis points and expert judgement. The basis for determining the buffer rate is the equal expected impact method, wherein the level of the O-SII buffer is set with a view to equalising the expected impact of an O-SII's distress on the overall system with the potential impact of a non-O-SII's distress. The rates determined in the process are shown in Table 1, and the results of the annual review were published on the website of the Croatian National Bank.

Table 1 Identified O-SIIs and their capital buffer rates

* Taking into account the status of the parent O-SII or G-SII in the EU, where applicable.

Source: CNB.

3.3 Warning of the European Systemic Risk Board on medium-term vulnerabilities in the residential real estate sector

On 11 February 2022, the European Systemic Risk board (hereinafter: 'the ESRB') issued a Warning on medium-term vulnerabilities in the residential real estate sector that may have a negative effect on the stability of the financial system in Croatia (ESRB/2021/13)[2]. The main vulnerabilities identified by the ESRB refer to the rapid growth in housing loans and possible signs of residential real estate price overvaluation, given the absence of explicit borrower-based macroprudential measures. In addition to identifying a moderate level of vulnerability, the warning specifies activities undertaken by Croatia so far to mitigate real estate market-related risk, in particular macroprudential measures based on additional capital requirements, the implicit debt service-to-income limit, the introduction of the legal framework for borrower-based measures and the collection of granular data on lending conditions in line with ESRB recommendation. Regardless of the low level of household indebtedness and the high capitalisation of the banking sector, the ESRB notes that the adoption of borrower-based macroprudential measures would complement the current capital-based measures in mitigating the possible accumulation of systemic risks associated with the concurrent increase in housing loans and real estate prices.

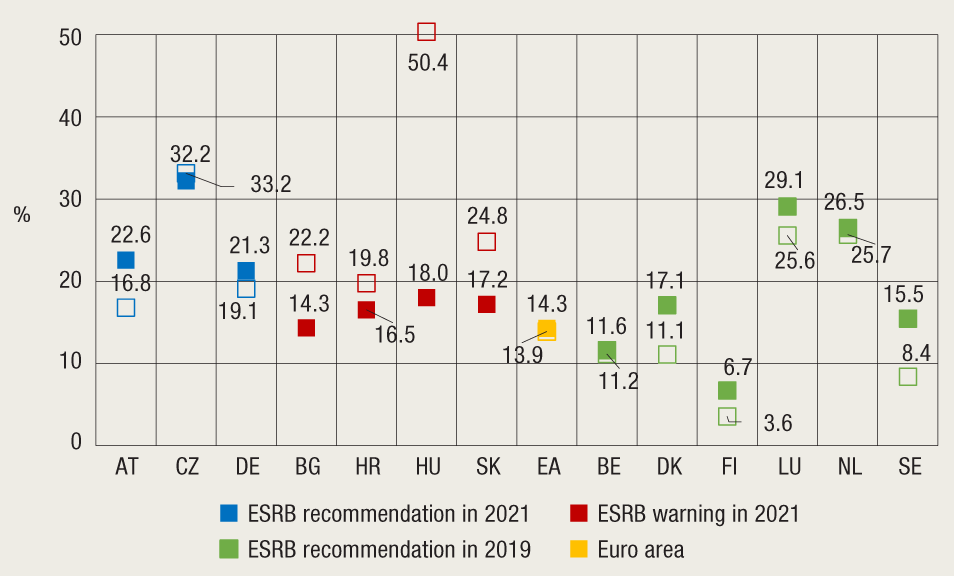

In addition to Croatia, warnings have been issued for Bulgaria, Hungary, Liechtenstein and Slovakia. Recommendations by which the ESRB, in addition to identifying vulnerabilities, proposes the implementation of measures aimed at their mitigation, have been issued for Austria, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands (Figure 6). The ESRB issued a press release specifying the countries which also received recommendations in the previous cycle of ESRB analysis performed in 2019 (Sweden, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Finland and Germany) and which failed to adequately address identified risks by macroprudential measures or in which the factors affecting the assessment deteriorated further in the meantime. The ESRB also issued a detailed report on the vulnerabilities related to the real estate market in EEA countries, on which the issued warnings and recommendations are based.

Figure 6 Average annual rate of growth in real estate prices in the three-year period preceding the issue of a recommendation or warning by the ESRB in 2019 and 2021, by country

Notes: Empty squares refer to the values of rates of growth in real estate prices in the period from the third quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2019; coloured squares refer to values of rates of growth in real estate prices in the period from the third quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2021. The data are available for all countries to which the ESRB issued a recommendation/warning on medium-term vulnerabilities in the real estate market in 2019 and 2021, except Liechtenstein.

Sources: Eurostat and ESRB.

3.4 Implementation of macroprudential policy in other European Economic Area countries

In the second half of 2021, European Economic Area member countries continued to tighten their macroprudential policy measures amid the recovery of the economy from the crisis brought about by the pandemic and accumulating risks in the residential real estate sector.

Several countries announced that they would be raising the countercyclical capital buffer rate. Iceland announced that it would increase the rate from 0% to 2%, to be applied as of the end of September 2022, due to the accelerated growth in household debt on the one hand and in property prices on the other, while Romania announced that it would raise its rate from 0% to 0.5% on account of the economic recovery and the associated increase in lending; the increase is to take effect in mid-October 2022. As of December 2022, Estonia will increase the countercyclical capital buffer rate from the current 0% to 1%. Bulgaria announced a similar decision, according to which it plans to gradually raise the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 1.5%: the rate is to stand at 0.5% by the end of September 2022, after which it will increase to 1.0% in the last quarter of 2022 and finally to 1.5% as of 1 January 2023. The rate will be raised to increase the resilience of the banking sector due to pressures on profitability caused by the potential deterioration of economic circumstances and losses associated with credit risk. With regard to the capital buffer rate increase announced earlier, Denmark amended its initial decision and is planning to raise the announced rate from 1% to 2% as of 31 December 2022. The Czech Republic also additionally increased the announced rate from 1.5% to 2%, to be applied as of 1 January 2023, while Norway announced that it would be raising the rate that it had previously reduced from 2.5% to 1% during the pandemic, so that from 31 December 2022, it would be 2%. The decision is justified by real estate price growth during the pandemic and the accelerated increase in household debt. Finally, Germany announced that it would lift the countercyclical capital buffer rate from the currently applied 0% to 0.75% as of February 2023, explaining its decision by the recovery of the economy following the COVID-19 pandemic, growing real estate prices and concerns over their possible overvaluation. In addition to the announced increases of the buffer rate, credit institutions are advised to take a conservative approach in the valuation of real estate and to exercise caution when granting larger loans, as well as to perform a thorough and comprehensive assessment of a borrower’s ability to meet credit obligations in case of interest rate increase.

Figure 7 The countercyclical capital buffer rate applied in European Economic Area countries by the end of February 2023

Note: The rates after 2022 refer to rates whose application was announced and which enter into force by the end of February 2023.

Sources: ESRB, notifications from central banks and websites of central banks as at 17 January 2022.

Lithuania announced that it would be introducing a structural systemic risk buffer to exposures secured by residential real estate as of 1 July 2022, as enabled by the amendments to the CRD from December 2020. The decision was adopted due to the accelerated growth in housing loans in 2021 coupled with the increase in their share in credit institutions’ portfolios, the rapid rise in real estate prices and their increasing deviation from fundamental values. It requested the ESRB to issue a recommendation on reciprocation with a de minimis threshold for exposures of credit institutions below EUR 50m. The reciprocation of this measure in Croatia will be considered after the ESRB issues the recommendation on its reciprocation.

As regards capital-based measures, to alleviate risks related to the real estate market, measures under Article 458 of the Capital Requirements Regulation (Regulation (EU) 575/2013, hereinafter: 'the CRR') were applied, prescribing risk weights for exposures secured by real estate for credit institutions applying the internal rating systems-based approach to calculate own funds requirements (IRB approach). As of 1 January 2022, the Netherlands introduced the measure whose adoption had previously been announced, but was postponed due to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. The measure prescribes the application of an average risk weight for exposures secured by residential real estate, depending on the loan-to-value ratio of the mortgage (for each exposure, a risk weight of 12% is applied for an LTV ratio up to 55%, and a 45% risk weight is applied for the remaining portion of the exposure). The CNB will decide on the reciprocation of this measure in Croatia after the ESRB issues its recommendation. The macroprudential authority of Estonia extended the application of the minimum average risk weight of 15% to retail exposures secured by residential real estate to obligors residing in Estonia for credit institutions applying the IRB approach. The duration of the measure is extended for two additional years, starting from its announcement in the third quarter of 2021. The reciprocation of the measure by other member states was not requested. The macroprudential authority of Sweden also extended the application of the measure adopted pursuant to Article 458 of the CRR for two additional years, until the end of 2023. The measure is applied to credit institutions using the IRB approach, and consists of a credit institution-specific floor of 25% for the average of the risk weights applied to the portfolio of retail exposures to obligors residing in Sweden, secured by residential real estate. By applying the envisaged exemption, in its Decision from 2019 the CNB announced that it would not reciprocate the measure specified above.

Member states actively implemented borrower-based measures as well, primarily to alleviate risks associated with the residential real estate market. As of 1 December 2021, Iceland set the maximum allowed debt service to income (DSTI) ratio to 35% (40% for first-time buyers), to be applied to all consumer loans secured by residential real estate. The measure was introduced with a flexibility quota of 5% on a quarterly level, applied to new loans secured by residential real estate. From the beginning of 2022, France began applying a DSTI ratio of 35% to all new housing loans and limited the maturity of housing loans to 25 years. A flexibility quota of 20% is applied on a quarterly basis to loans granted to first-time buyers of primary residences and owner-occupiers.

Box 2 Improvements in the methodology of countercyclical buffer identification and calibration in Croatia

The countercyclical buffer (CCyB) is a releasable macroprudential instrument used to mitigate cyclical systemic risks that may arise from excessive lending to the private non-financial sector. Exposure to cyclical systemic risks increases during the upward phase of the financial cycle, but usually becomes evident later, when the cycle reverses. Countercyclical buffer build-up in the upward phase of the cycle ensures a timely allocation of additional capital. This, in turn, enables credit institutions to absorb losses and maintain lending activity more easily in the downward phase of the cycle or in the event of a sudden crisis. Furthermore, buffer build-up in the upward phase of the financial cycle may contribute to the mitigation of credit growth and the reduction of financial cycle amplitudes.

The CCyB rate is evaluated and identified on a quarterly basis. It is applied to the total amount of a credit institution’s risk-weighted exposures. According to the provisions of harmonised European regulations, the CCyB rate is to be applied 12 months after the decision on its application is adopted in order to allow credit institutions enough time to collect the required capital. The methodology containing the guidelines for identifying the CCyB in EEA countries has been recommended by the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). The starting point for determining CCyB levels is the standardised credit gap indicator calculated in line with the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) guidelines. This indicator of excessive credit growth is easily calculated and interpreted; the statistical data necessary for its calculation are available for a large number of countries and it has performed well at signalling previous systemic crises. However, bearing in mind the specificities of national economies and considerable differences in the length of available time series across member states, the ESRB has also foreseen the option of calculating an additional, "specific" credit gap indicator that better reflects the specificities of a national economy and has better crisis signalling properties.

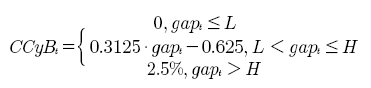

The credit gap is calculated as the difference between the credit-to-GDP ratio and its long-term trend value obtained by statistical filtering (using the Hodrick-Prescott filter, HP), i.e. gap = ratio trend. Based on the experience of a group of countries from the period prior to the onset of the last global financial crisis, the benchmark CCyB value based on the standardised Basel credit gap is defined as follows:

where the gap variable is the credit gap defined as the difference between the ratio and the trend, and L and H are the lower and upper thresholds of 2 and 10 respectively.

In addition to the standardised Basel credit gap indicator, the Croatian National Bank has, until now, used a specific credit gap indicator for the Republic of Croatia. This gap was defined in 2014 when the CCyB was adopted as one of Croatia’s macroprudential instruments[3]. To calculate the specific credit gap, L and H values may deviate from those specified above, depending on evaluation results. It is necessary to note that the estimated CCyB rate is not automatically included in the decision on the required CCyB rate, but rather serves as a starting point. Other relevant and available data for the national economy are also taken into account when making the final decision. The developments in the Basel and the specific credit gap and relevant benchmark CCyB rate values are published quarterly in Announcements. Since the introduction of this instrument in Croatia’s macroprudential framework in January 2015, the CCyB rate has remained at 0%.

Both applied indicators, the Basel standardised credit gap and the specific credit gap, were negative at the moment of initial calibration (2014) and declined further in the period that followed. This was a result of a period of sharp credit growth prior to the global financial crisis and the subdued growth over the entire period thereafter. Both indicators would move into positive territory only after a long period of relatively strong credit growth, possibly leading to the late adoption of the decision to increase the CCyB rate, at a point when the system has already accumulated significant cyclical risks. Moreover, the specific gap indicator which observes loans in relation to quarterly GDP values (as opposed to the annual GDP used for calculating the Basel, or standard credit gap) has become exceptionally volatile since the onset of the pandemic. This makes reaching the conclusion on the need to increase and/or reduce the CCyB rate even more difficult, especially over short periods of time. The plunge in GDP in the second quarter of 2020 resulted in a strong credit gap increase, with the specific indicator even moving into positive territory according to calculations made at the time, which would suggest the need to set a positive CCyB rate (see Announcement). Such gap indicator behaviour is unwelcome because, as a rule, capital buffers are not built in the conditions of materialised risk, or during economic activity contraction. This is why the required rate was set to remain at 0%.

To mitigate or correct the aforementioned deficiencies and improve the calibration methodology (CCyB), a broad set of potential credit gap indicators was reviewed along with other measures of cyclical risks. The goal was to find new, alternative indicators with better early warning properties than the Basel or the specific credit gap indicator. To improve the methodological soundness of credit gap indicators, in addition to various changes in the definition of the ratio and in the long-term trend assessment, corrections in the statistical filtering of time series were considered as well. Specifically, the Basel methodology implicitly assumes a 30-year duration of a financial cycle, which is reflected in the choice of the smoothing parameter in HP filtering. On the other side, empirical research[4] has shown that cycles may also be shorter. In addition to calculating new credit gap indicators, a composite financial cycle index has been created which, in a standardised manner, combines a broad set of indicators monitored by the CNB when assessing systemic cyclical risks. The selected risk indicators associated with credit activity, real estate market developments, private sector debt, external imbalances, the quality of credit institutions’ balance sheets or risk mispricing have thus been synthesised in a single index, the indicator of cyclical systemic risk (ICSR). The new specific credit gap indicators and the composite ICSR are described below; they constitute an improved methodology for countercyclical buffer identification and calibration in Croatia, created to enable a more accurate and timely adoption of the decision on the CCyB rate.

New specific credit gap indicators

Desirable statistical properties of the credit gap indicator in the literature[5] include the ability to provide an early warning of a financial crisis (timely and accurate crisis signalling and the absence of incorrect crisis prediction) and the stationarity and stability of the indicator. The chosen indicator should thus consistently signal the accumulation of systemic risks over a certain period, i.e. it should not be sensitive to the addition of new data to the existing time series (the indicator should not change conclusions significantly once new information has been added).

Several methodological changes have been implemented to construct alternative credit gap indicators. Credit indicators have been defined in two different ways: as narrow, i.e. bank loans to households and non-financial corporations, and broad, i.e. bank loans enlarged by other bank claims and external debt. Furthermore, the GDP seasonal adjustment method has been adjusted by extrapolating one-off and transitory shocks along with the seasonal component. Since business and credit cycles do not necessarily overlap or last for the same amount of time, loan series and GDP series were filtered[6] separately, and only after that was their ratio calculated. Finally, in addition to the absolute gap that has until now been calculated in line with the requirements set out by the BCBS and the ESRB Recommendation, the relative gap (the ratio between credit ratio and its trend, as %) has been analysed as well in line with the proposition made in the ESRB paper on the operationalisation of the countercyclical capital buffer (2014).

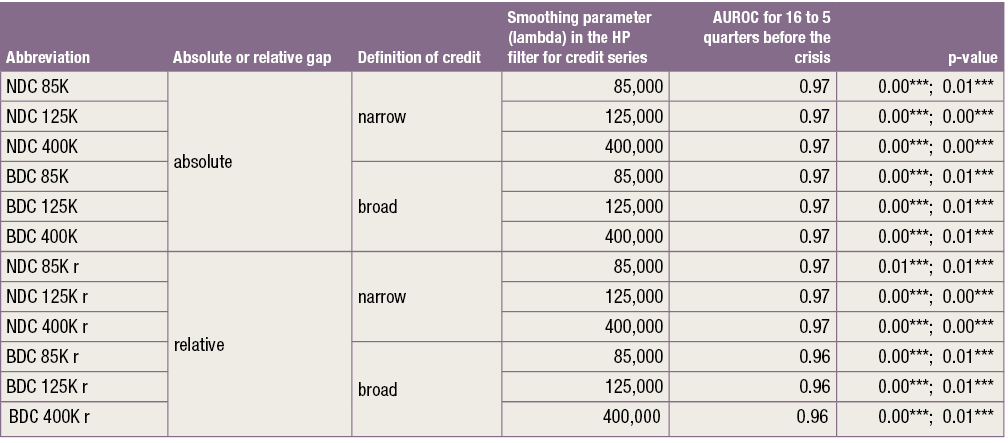

To select the best credit gap indicators for CCyB calibration, the common signalling approach to the early warning model was used, i.e. formal statistical tests[7] were applied to select indicators with best crisis prediction properties. Systemic crisis was defined as the period between October 2008 and June 2012. The signalling period for the crisis onset was set to be identified at least three to five quarters ahead, in order to leave enough time for capital accumulation in the pre-crisis period. Crisis period dates were chosen in line with the ESRB recommendation and the literature describing crisis periods or dealing with developments in the Croatian banking market.

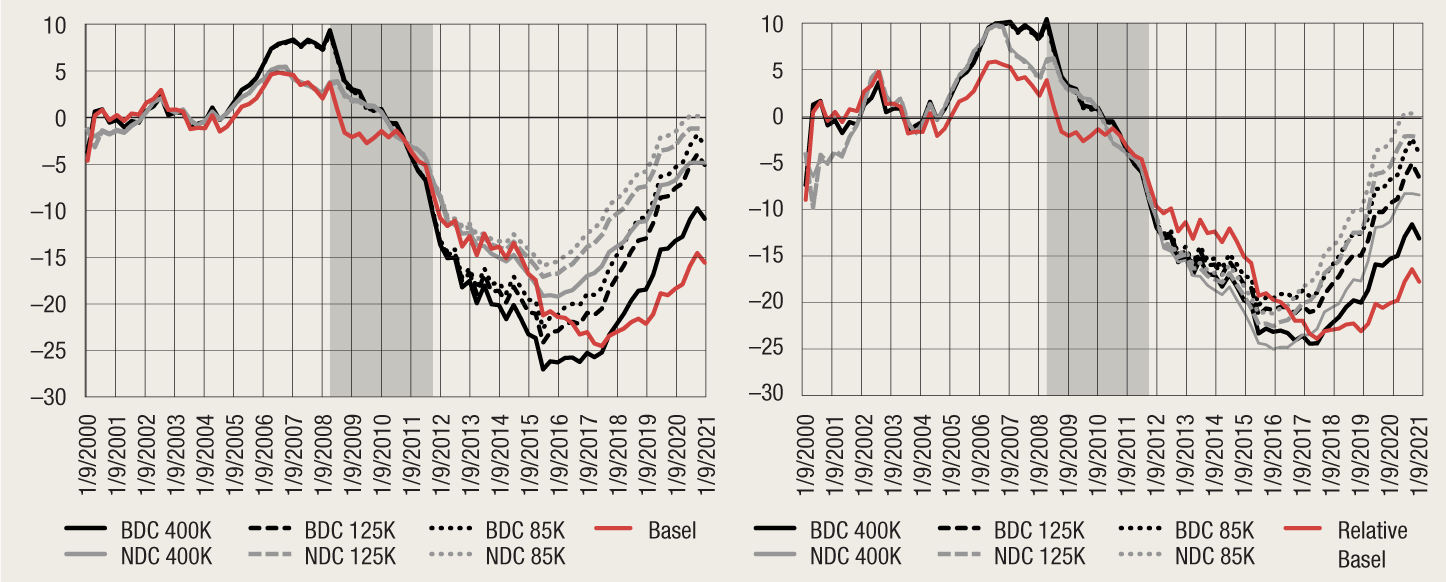

Analysis results (Table 1) demonstrate that a total of twelve credit gap indicators have better crisis signalling properties than the currently applied Basel and specific credit gap indicators. Figure 1 shows that the selected credit gaps increased earlier and more sharply than the Basel and the specific credit gap indicator in the period before the global financial crisis. In the same way, the negative gap is closing faster in the current cycle, and in some cases, it is already moving into positive territory. This is a result of a halt in private sector deleveraging and the stabilisation of the credit-to-GDP ratio over the past several years, coupled with a gradual decline in its long-term trend. The elevated level of the long-term trend in the post-crisis period is a result of the filtering method applied to the data that have increased exceptionally strongly in the period before the great financial crisis. This could be the reason why it may be assumed that (negative) gaps are somewhat underestimated. Furthermore, new gaps are less sensitive to sudden GDP shocks than the specific indicator originally used and are less volatile.

Table 1 Short description of gaps with better crisis signalling properties than the Basel and specific indicators currently used

Notes: Each of the gaps in Table 1 has been obtained by special filtering applied to the credit series using smoothing parameters specified in the table, while the GDP series has been filtered using a parameter of 1,600. The p-value refers to the p-values of the DeLong one-sided test where the null hypothesis assumes that the selected indicator has a lower AUROC value than the Basel indicator (left) and the specific indicator applied thus far (right). ** and *** indicate significance of 1% and 5% respectively. The absolute gap is calculated as the difference between the credit ratio and its trend, while the relative gap is calculated as their ratio reduced by 1 and multiplied by 100%.

Source: CNB.

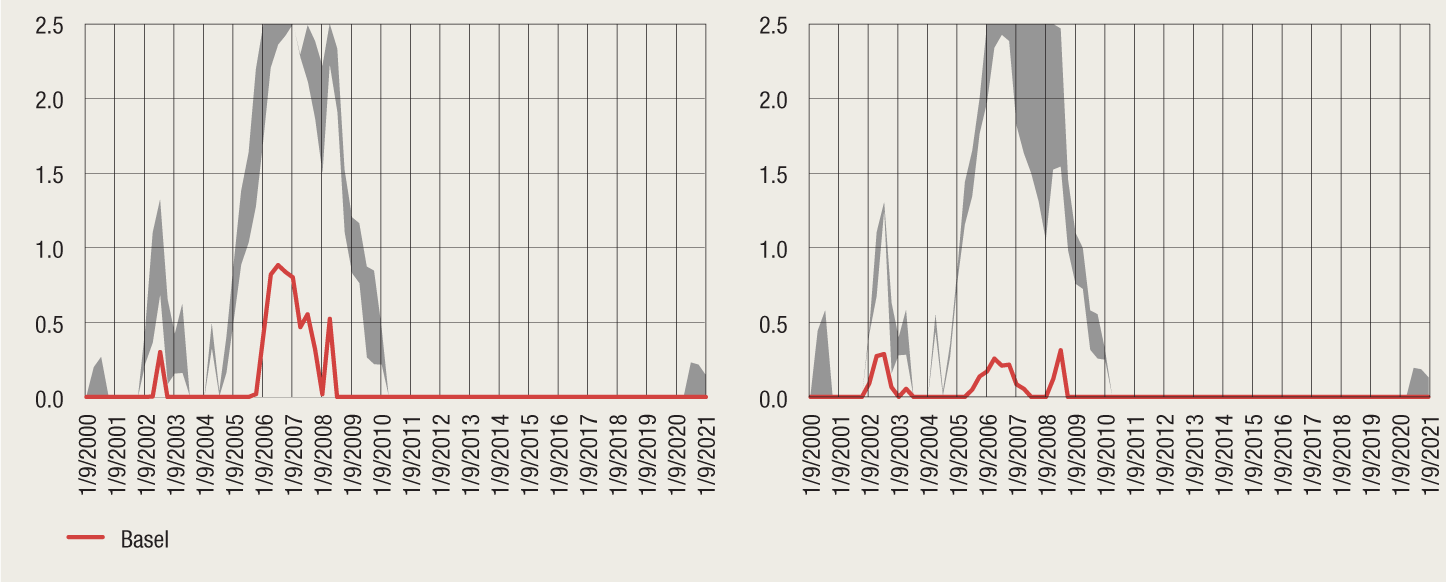

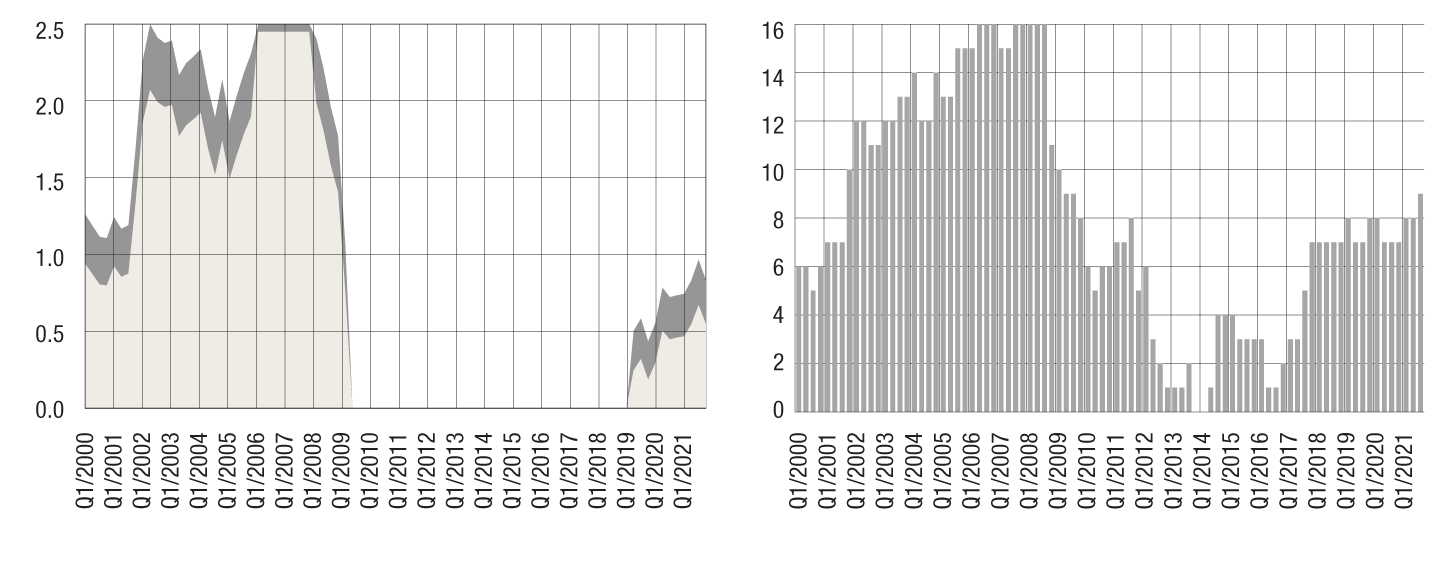

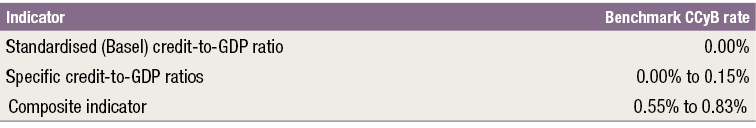

The benchmark CCyB rate for each indicator has been calibrated based on the indicators with best signalling properties, and their range (from the minimum to the maximum value in a given quarter) is shown in Figure 2. Formula (1) has been adjusted according to the thresholds estimated in this research. In line with the behaviour of the range of the estimated gap, calibrated CCyB rates take on positive values earlier than the Basel and the specific gap that have been used thus far at the CNB (Figure 2). This provides more time to build up a CCyB and implies somewhat higher CCyB rates than those based on the Basel and the specific indicator. As well as in the years preceding the global financial crisis, such developments have been noticed recently as well, with two of the estimated twelve indicators taking on positive values in 2021 and thus indicating the need to set a positive CCyB rate.

Figure 1 New specific credit gap indicators

Notes: Abbreviations are explained in Table 1; the absolute gap is calculated as the difference between the credit ratio and its trend, while the relative gap is calculated as their ratio reduced by 1 and multiplied by 100%. The Basel credit gap refers to the indicator used by the CNB thus far. The following indicators are, consecutively, closest to 0 (listed below from the closest to the farthest): NDC85K, NDC125K, NDC85K and NDC400K. The shaded area indicates the crisis period.

Source: CNB.

Figure 2 Range of CCyB benchmark rates for new specific indicators shown in Figure 1

Note: The positive value of the CCyB at the end of the observed period is signalled by the NDC85K gap in both panels.

Source: CNB.

Composite indicator of cyclical systemic risk

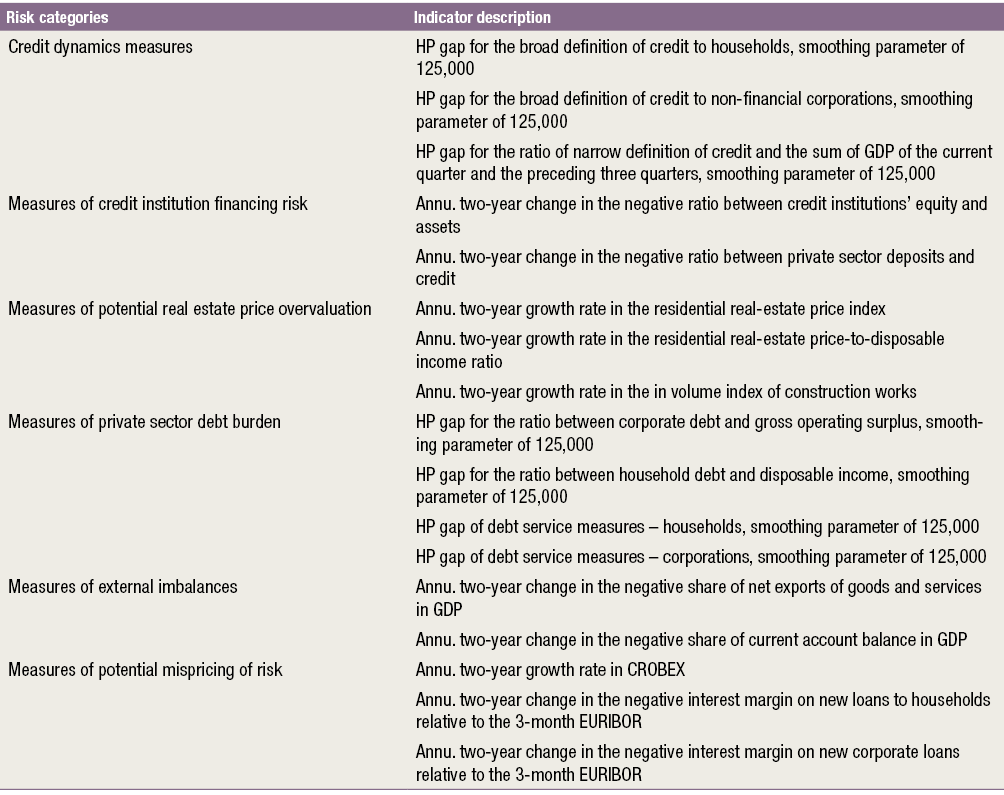

In addition to the new specific credit gaps, a new composite indicator of cyclical systemic risk (ICSR) is monitored, based on six groups of indicators related to excessive credit growth, as recommended in section C of ESRB recommendation (2014) providing guidelines on the management and operationalisation of the CCyB. Based on the methodology[8] described in Lang et al. (2019), two composite indicators were constructed. In the first variant, individual indicators were selected within the aforementioned six categories of risk which performed the best in signalling the previous crisis in Croatia. In the second variant, indicators and their shares in the composite indicator were directly applied according to the aforementioned paper[9]. Here, the idea was to confirm the alignment of information contained in the Croatian indicator with the results obtained from research on the international dataset (narrow indicator variant). Table 2 shows the definitions of variables contained in the broad composite indicator, which will, along with credit gaps, primarily be used when making decisions on the CCyB rate. These indicators were selected by applying the same signalling model to a broad set of data, as described earlier using the example of alternative credit gap indicator selection. However, since different variable transformations were used in the analysis, in addition to signalling quality, stability was also considered in the selection (for example, even though in some cases, the two-year growth rate performed better at crisis signalling, the gap estimated using the HP filter was selected because its dynamics was more stable over the observed period). Finally, when constructing the composite index, equal weights (1/6) were assigned to each of the six cyclical risk categories, and indicators included within each group were also weighted equally.

Table 2 Selected indicators for the construction of the indicator of cyclical systemic risk (ICSR)

Note: “Annu.” indicates that two-year changes/growth rates have been annualised (values divided by 2).

Source: CNB.

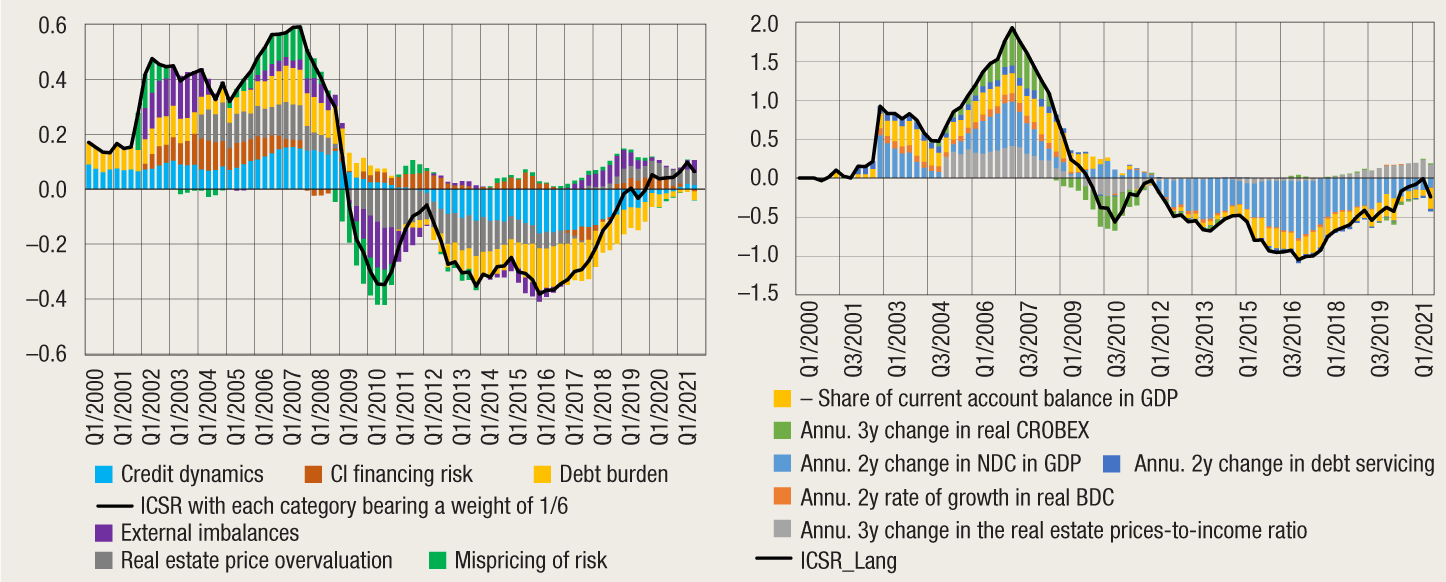

Figure 3 shows the dynamics and composition of the ICSR (narrow and broad variant), which peaked in the period of economic upswing before the global financial crisis with contributions from all included indicators. Once the global financial crisis began and the Croatian economy fell into a several-year long recession, indicator value began to fall sharply as a result of the slowdown in credit growth, the decline in residential real estate prices and the decrease in external imbalances. The lowest indicator value was recorded at end-2016, after which it began to recover, a trend continuing, with certain interruptions, until today. The upward trend in index movement indicates the recovery in the credit and the financial cycle characterised by low risk perception and systemic risk accumulation. Since 2017, the most significant contribution to the increase in broad ICSR has come from growing residential real estate overvaluation, accelerating credit activity and the increase in private sector debt burden.

Figure 4 (left panel) shows the proposal for CCyB calibration using the ICSR, based on indicator distribution properties, under the assumption of higher or lower prudence in determining the lower and upper threshold for setting a positive rate. The lower threshold for the calibration of the CCyB rate has been chosen to enable the rate to become positive before indicators included in ICSR calculation reach median level (i.e. medium level of cyclical risk accumulation), while the upper threshold is determined by the highest percentiles of ICSR distribution. The maximum (100th percentile) has not been taken into account as this indicator value was specific for the period preceding the global financial crisis. This enables higher CCyB rate sensitivity to ICSR movements. In addition, the right panel of Figure 4 demonstrates the number of indicators within all ICSR categories exceeding the lower threshold indicating the need to maintain a positive CCyB rate.

In conclusion, the range of the CCyB rate based on ICSR movements also reflects the accumulation of cyclical risks in Croatia and the need to set a positive CCyB rate. It appeared for the first time in the first quarter of 2019, and in the first quarter of 2020, the lower threshold of estimated CCyB rates exceeded the level of 0.50%. However, since the crisis caused by the pandemic had already begun at the moment these data became available, the CNB decided to maintain the CCyB rate at 0%. Economic activity stabilised in the meantime, and ICSR still points to a relatively early stage of cyclical risk accumulation, so that the benchmark CCyB rate has been calibrated in the model within a range between 0.55% and 0.83%.

Figure 3 Composition and dynamics of the composite indicator of cyclical systemic risk (ICSR) in Croatia (left panel) and the narrow variant according to Lang et al. (2019) (right panel)

Notes: CI indicates credit institutions. “Annu.” means annualised. See footnote 7 for variable description in the right panel.

Source: CNB.

Figure 4 Range of calibrated benchmark CCyB rates based on the ICSR and the number of variables crossing the lower threshold for setting a positive rate

Source: CNB.

In conclusion, the developments in the credit gap indicators and the composite indicator of the financial cycle, as well as other relevant data, suggest that the Croatian economy is currently in an upward phase of the financial cycle, which implies growing cyclical systemic risks. Bearing in mind the results of the early warning model and the developments described above, it is estimated that at this point, the CCyB rate needs to be elevated to 0.5%, taking effect in 12 months.

Table 2 Relevant indicators of cyclical systemic risk and benchmark countercyclical buffer rates

Source: CNB.

Table 1 Overview of macroprudential measures applied by EU member states, Iceland and Norway

Notes: The listed measures are in line with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (CRR) and Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (CRD IV). The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication. Green indicates measures that have been added since the last version of the table. Light red indicates measures that countries have released in response to the crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic. Disclaimer: of which the CNB is aware.

Sources: ESRB, CNB, notifications from central banks and websites of central banks as at 17 January 2022.

For details, see:

https://www.esrb.europa.eu/national_policy/html/index.en.html and https://www.esrb.europa.eu/home/coronavirus/html/index.en.html.

Table 2 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

Note: The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of abbreviations at the end of the publication.

Source: CNB.

-

Shamloo, M., E. Nier, R. Popa and L. Voinea (2019), Debt Service and Default: Calibrating Macroprudential Policy Using Micro Data, IMF Working Papers 2019/182, International Monetary Fund. ↑

-

Warnings and recommendations carry different weight and imply different expectations of the member state they are issued to. Warnings are a milder form used by the ESRB to describe the current state of affairs and to propose measures, instruments or legislative amendments that may lead to positive shifts; as a result, in the period following its issuance, the ESRB monitors whether the systemic risk specified in the warning is being adequately addressed. On the other hand, recommendation points to a more significant level of systemic risk, and is issued separately or as a result of insufficient action taken following the issue of a warning. After a recommendation has been issued, in monitoring the action taken by the member state to address systemic risk, the member state is expected to act in accordance with the proposals in the recommendation or to justify any inaction or action contrary to the recommendation (“act or explain” mechanism). ↑

-

The analytical background and the calculation of the “specific” credit gap for Croatia were published in the CNB publication Financial Stability No. 13 (2014), Box 4. The first Decision on the countercyclical buffer rate was adopted in January 2015. ↑

-

See e. g. Drehmann et al. (2010), Galán (2019), Valinskytė and Rupeika (2015) or Edge and Meisenzahl (2011). ↑

-

Kauko (2012), Drehmann and Tsatsaronis (2014), Drehman and Juselius (2013), Önkal et al. (2002) and Lawrence et al. (2006). ↑

-

Relatively short time series of financial variables make the evaluation of credit cycle duration length in Croatia difficult, so, based on the findings from the literature, it is assumed to be two to four times longer than the business cycle. In the HP filter, the smoothing parameter (lambda) is set at various values: 25,600, 85,000, 125,000 and 400,000, with higher parameters implying longer financial cycle durations. In the separate GDP filtering, lambda is set at 1,600, as is usual with quarterly GDP data. ↑

-

For details on the methodology, see Kaimnsky and Reinhart (1999), Borio and Drehman (2009), Drehman et al. (2010, 2011). The best indicators were selected based on the AUROC (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) value and true positive rate and false positive rate values measuring the discriminatory power of the estimated model. All applied indicators were tested for four crisis signalling spans (12 to 5, 20 to 3, 12 to 7 and 16 to 5 quarters ahead of the crisis). Table 1 shows the signalling results for 16 to 5 quarters prior to the crisis. ↑

-

See the aforementioned paper, Lang et al. (2019) for the description of the entire methodology. Rather than applying standardisation using the median and the standard deviation of each variable, for the broad ICSR, a min-max normalisation approach has been used, whereby each transformed variable obtains values within the interval (–1, 1). Such transformation has been chosen because standardisation is not considered the optimal approach in cases where variables are not normally distributed. In the narrow indicator variant, standardisation using the median and standard deviation of each variable was performed following the approach used in the aforementioned paper. Therefore, in addition to the selection of different variables, the dynamics of respective composite indicators vary to a certain extent as well. ↑

-

Annualised two-year change in the ratio of credit (NDC)) to GDP (36%), annualised two-year real credit growth rate (BDC) (5%), annualised three-year real estate price-to-income ratio change (17%), the share of the current account balance in GDP (20%), annualised two-year debt service-to-income ratio (DSR) change (5%) and the annualised three-year change in the real stock market index (17%). ↑