Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 19

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected, according to calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of events that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to the structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1 Identification of systemic risks

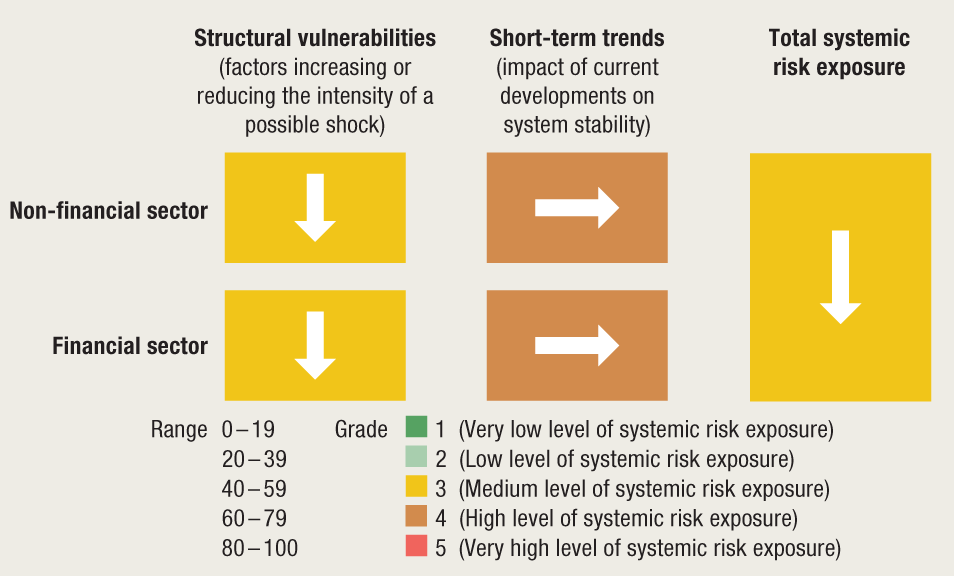

The total exposure of the financial system to risks decreased slightly at the turn of the year 2022 to 2023, primarily as a result of currency risk being eliminated thanks to the entry into the euro area (Figure 1). Although macroeconomic expectations for 2023 seem more optimistic than in the preceding period, amid geopolitical uncertainties, high inflation and the global economic slowdown remain the main sources of risks to financial stability in Croatia. In addition, against the backdrop of growing interest rates and declining real income, the growth in household and corporate loans is increasing the debt repayment burden and may result in difficulties in debt servicing. Cyclical risks linked to the real estate market are elevated in consequence of the strong growth in prices and housing loans.

Figure 1 Risk map, fourth quarter of 2022

Notes: The arrows indicate changes from the risk map published in Macroprudential Diagnostics, No. 18 (October 2022).

Source: CNB.

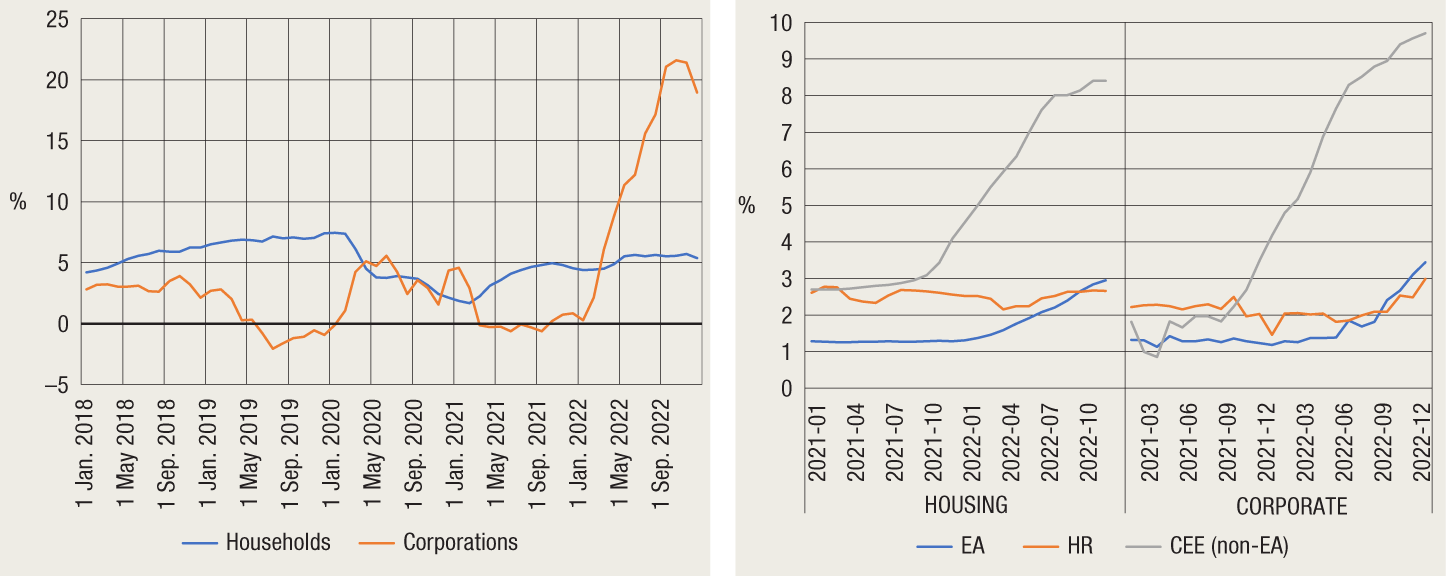

At the end of 2022, global financial markets were still negatively affected by the slowdown in economic activity, persistent inflation and monetary policy tightening. Share and bond indices decreased significantly in 2022, as did the asset value of various types of investment funds, but this did not lead to significant pressures on liquidity. Costs of public and private sector funding grew, with Europe witnessing stronger growth in interest rates in countries outside the euro area than in countries within it (Figure 5). At the same time, the tightening of the Fed’s monetary policy led to an inversion of the yield spread between the ten-year and the two-year US government bond, pointing to a higher probability of the economy sliding into a recession.

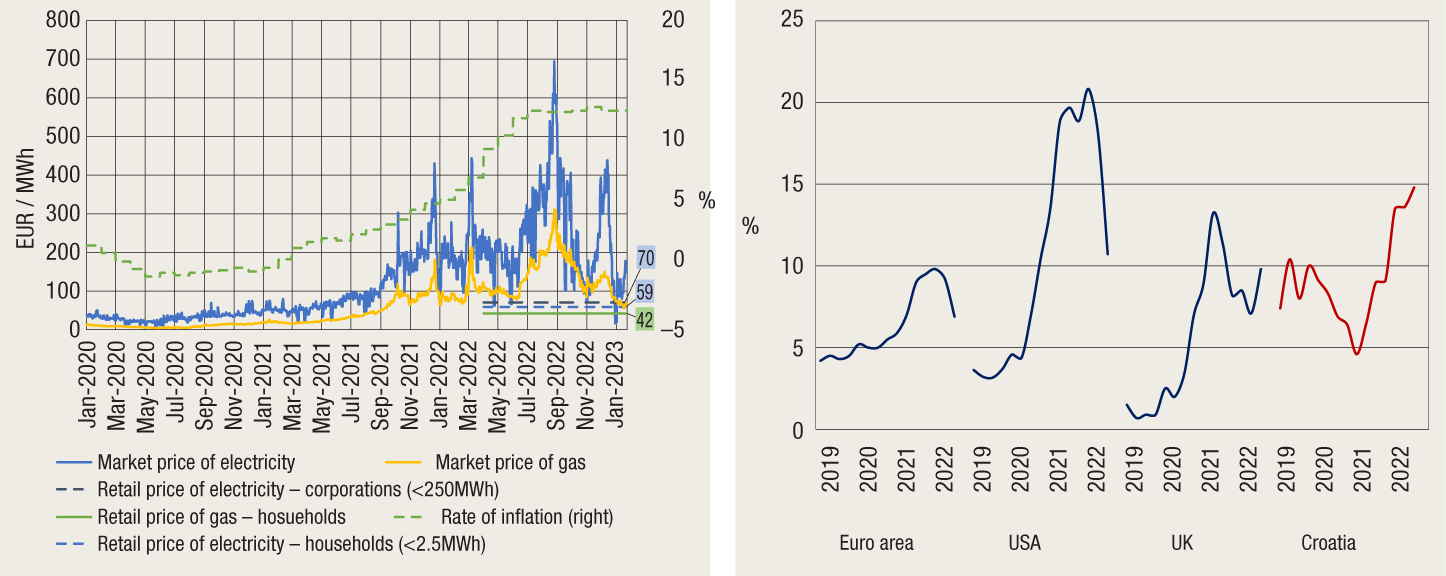

The effects of heightened geopolitical uncertainty, economic slowdown and strong inflationary pressures that prompted monetary policy tightening gradually spilled over to the Croatian economy in the course of 2022. Even though consumer price inflation slowed down in December under the influence of a drop in energy and food prices on global markets to levels recorded in early 2022 (Figure 2), core inflation continued to grow, reaching a level twice as high as that recorded in the euro area. The fiscal position increased in the current year as a result of solid economic growth, higher price levels and the still relatively low interest rates. However, a possible prolongation of the broad-based fiscal support introduced with the aim of mitigating the consequences of inflation could strengthen the risk to public finance sustainability amid slower economic activity and increased borrowing costs.

Up to now, the effect of the ECB's increase of key interest rates has spilled over to Croatia to a limited extent. The harmonisation of the set of monetary policy instruments in the process of euro introduction resulted in a significant decrease in regulatory requirements and an increase in liquidity surpluses, which delayed and mitigated the intensity of the spillover of tighter financing conditions from European markets to Croatia. By the end of December 2022, the cost of borrowing increased noticeably for the government and non-financial corporations, but not for households (Figure 5). Yields on Croatian bonds increased to the same extent as the average yield of euro area countries, while yields on the bonds of Central and Eastern European countries rose significantly more. The average interest rate on newly-granted loans to non-financial corporations increased by slightly more than one percentage point in the second half of 2022, and due to such developments, it was even lower than the euro area average towards the end of the year. The average interest rate on residential loans contracted for the first time increased only slightly in November and December and was also lower than in the euro area.

Interest rates on household loans could see a more noticeable increase in the course of the current year. Specifically, as of January 2023, a slight increase in interest rates has been observed in the offer of new residential loans of banks, with a lag still noticeable in the intensity of the increase compared with the rest of the euro area. Additional liquidity surpluses and low financing costs from deposits coupled with the hike in the ECB's key interest rates had a favourable effect on the profitability of credit institutions even without a significant rise in interest rates on loans. Furthermore, the intensity of the increase in interest rates on existing loans with variable interest rates has been dampened by legal restrictions on maximum interest rates.

| Figure 2 Inflation and energy prices Figure 3 Residential real estate price trends |

|

| Notes: In the left figure, gas and electricity prices refer to the European market. Source: Bloomberg, FED, Eurostat and CNB calculations. |

The strong growth in corporate loans amid rising interest rates is increasing the corporate debt repayment burden, although interest rates are climbing from historical lows. Loans to non-financial corporations increased substantially last year (by 19.0%), with one third of loan transactions directed at corporations from the energy sector, which increased their debt considerably (Figure 4). Within the sector, loans for working capital saw a particularly strong growth, as they were used to finance reserves, bridge the gap between the prices for energy distribution to end customers formed by the market and those regulated by the government’s package of measures and to ensure the smooth distribution of energy. Despite the significant reduction of prices of energy in the second half of 2022 (Figure 2), energy companies are still vulnerable to possible unfavourable effects of caps on the selling prices of energy. Nevertheless, the entire non-financial corporate sector increased its income in 2022 to an extent exceeding the overall price growth, which increases its resilience to shocks. The debt repayment burden has grown only slightly thus far considering the slower spillover of the increase in market interest rates and the relatively high share of fixed-interest rate loans, so that no increase in the non-performing placements of banks to corporations has been recorded yet. However, the continued spillover of tighter financing conditions and the gradual maturing of loans granted at a fixed interest rate in the upcoming period will probably increase credit risk in the corporate segment.

|

Figure 4 Growth in loans to the private sector |

|

|

|

|

Note: Figure 4 shows transaction-based rates of change over a 12-month period; the figure on the right shows interest rates on the new business volume of loans (corporate loans exclude revolving loans, overdraft facilities and credit cards); EA refers to euro area average and CEE (outside of EA) shows CEE countries outside of the euro area. |

|

|

Source: ECB and CNB calculations. |

|

The continued decline in the real income of households and the increasing share taken by consumption in disposable income coupled with growing interest rates are increasing risk for households. As is the case with corporations, the increasingly common practice of opting for interest rate fixing, at least during the initial loan repayment period, will mitigate the effect of interest rate increases on the rise in loan repayment costs of households. The intensity of repayment cost increase is also dampened by the caps on the maximum allowed interest rates. However, for some loans, interest rates will transition from fixed to variable over the medium term and the increase in market interest rates could drive legal caps on interest rates up. Consumers can protect themselves from interest-rate risk by agreeing on the temporary or permanent fixing of interest rates (see Information list with the offer of loans), with some banks offering this option in accordance with the CNB’s Recommendation from 2017[1].

The rise in residential property prices picked up considerably over the course of 2022, which increases the risk of a price slump. The annual rate of residential real estate growth in the third quarter of 2022 rose to 14.8%, although most EU countries recorded a slowdown in real estate price growth, with some even witnessing a decline (Figure 3). At the same time, the number of realised purchase and sale transactions has been stagnant in the domestic market since 2021. Housing loans, however, continued to grow at relatively high rates, which contributes to the accumulation of cyclical systemic risks. In order to limit possible unfavourable effects of cyclical risk materialisation, including the materialisation of risks stemming from the real estate market, the CNB announced that it would increase the countercyclical capital buffer rate (see Chapter 3). The new round of housing loan subsidies announced for spring 2023 will continue to support the demand for housing loans, which could, paired with a relatively limited offer of new real estate, exert further upward pressure on prices. On the other hand, higher living costs, declining real income and the anticipated interest rate increase, which reduce the affordability of real estate and particularly the capability of financing real estate purchase via loans, could have an unfavourable effect on market liquidity and, consequently, residential real estate prices.

Although the capitalisation of credit institutions went down in 2022, it is still significantly above the prescribed level, which significantly contributes to the stability of the financial system. Total capital ratio decreased as a result of capital decline under the influence of unrealised losses based on the valuation of bonds at fair value and the increase in risk-weighted assets, standing at 24% at the end of the third quarter of 2022. The share of stage 3 loans continued to decline, reaching historical lows, primarily due to their recovery, and to a lesser extent, due to sale. However, stage 2 loans continued to increase, which points to growing credit risk. Bank profitability is relatively high, and several larger banks could, due to a considerable increase in profitability, be subject to one-off excess profit tax (see Box 1).

At the beginning of 2023, Croatia introduced the euro as its national currency, which brought numerous long-term benefits for the overall economy and the financial system, but also one-off costs for banks. By the adoption of the euro, banks permanently lose a portion of their future profits (almost 10% of net operating income), mostly related to foreign exchange trading and the fees resulting from currency exchange business and international payment transactions; in addition, they suffered costs related to the adjustment of the IT system and the replacement of cash in circulation. On the other hand, benefits for the banking sector arise from an almost complete elimination of currency risk, a stronger and more resilient domestic economy, direct access to the monetary operations of the European Central Bank and, if necessary, in case of crisis, to European Stability Mechanism funds. The CNB became a lender of last resort in the true sense of the term, as it is able to provide, under special circumstances, support to liquidity in euro. In addition to the long-term benefits stated above, the net effect of euro introduction in the current year should also be positive, as the harmonisation of monetary policy instruments significantly boosted liquidity and reduced regulatory costs, while the overnight deposit facility offered by the central bank for the depositing of excess liquidity at the currently applicable interest rate of 2.5% significantly increases income for banks.

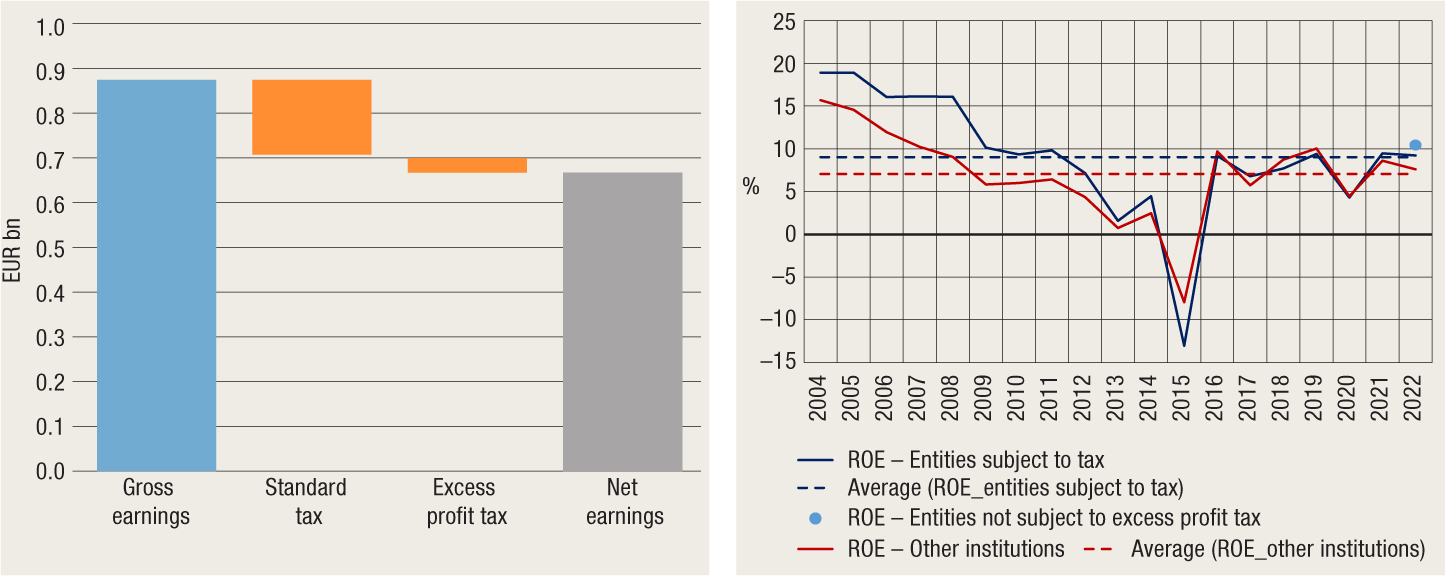

Box 1 Estimation of the effect of excess profit tax on banks

In some countries, financial institutions are subject to special tax in addition to regular tax; for example, after the global financial crisis, some countries resorted to the additional taxation of banks. The aim of such taxes was to increase government revenues, particularly those directed at the funding of various mechanism for the preservation of financial stability, such as resolution funds. Certain countries introduced a bank asset tax (e.g., Poland, Slovenia, Hungary) and a bank liability tax (e.g., Germany, Sweden, Austria).

Until now, Croatia has never introduced special bank taxes, but in 2023, some banks could be subject to the new corporate excess profit tax, introduced in 2022 with the aim of additionally taxing corporate windfall profits[2], due to, among other things, price increases. Numerous other EU countries[3], motivated by the strong growth in energy prices and following the recommendation of the European Commission of March 2022, also introduced windfall taxes, although they were mainly directed at corporations in the energy sector. Only a few countries decided also to tax financial institutions (Czech Republic, Hungary) or all large corporations, including banks (Poland), as is the case in Croatia.

According to preliminary unaudited data, in 2022, banks operating in Croatia generated gross profits similar to those recorded in 2021, although in the first three quarters, their profits were 25% higher than in the same period in the year before. This will result in a financial obligation for banks to pay an amount slightly above EUR 150m under regular profit tax and some EUR 25m more based on excess profit tax (Figure 1). Only a small number of a total of eight larger banks will be subject to excess profit tax based on the income criterion. The excess profit tax will decrease the return on equity of banks subject to the tax by roughly one percentage point, reducing it to a level around its long-term average (Figure 2). Still, the ROE of such banks should still exceed that of banks that are not subject to the excess profit tax.

|

Figure 1 Estimation of the effect of excess profit tax on the banks’ earnings |

|

|

|

|

Source: CNB calculations. |

The effect of the tax on the excess profit of banks on financial stability should be negligible, while the potential effect on the availability and cost of loans should be very limited. Empirical research[4] indicates that the possibility of a transfer of the new tax burden to clients depends on its economic significance, but also on the elasticity of the demand for loans, i.e., on the competition on the market. In the case of Croatia, the estimated amount of tax is relatively low compared with the net earnings of banks covered by the tax, and the competition among banks[5] should prevent any tightening of financing conditions based on the new tax that would exceed the extent to which they are currently expected to tighten due to monetary policy contraction, particularly considering that only a small number of banks, albeit large ones, will be subject to the tax. Furthermore, in contrast to earlier bank taxes introduced in other countries, excess profit tax in Croatia is a one-off tax, which should also reduce its potentially negative impact on financing conditions.

2 Potential risk materialisation triggers

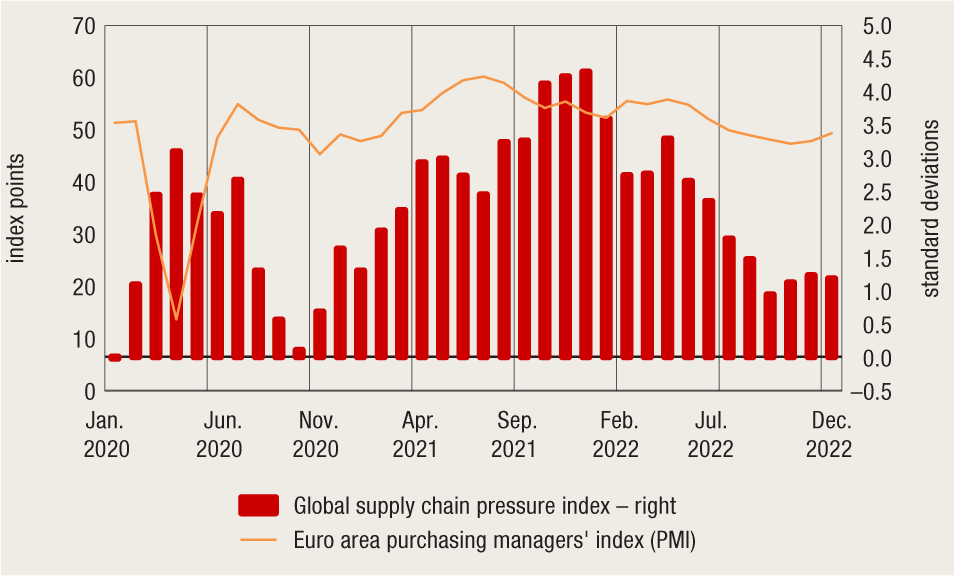

Threats to financial stability primarily stem from the international environment in the form of a possible further tightening of the global geopolitical situation and the deterioration of the epidemiological situation in China, which, combined, could lead to the disruption of global supply chains and additional upward pressures on prices. Considering the uncertainty regarding the duration and the intensity of the war in Ukraine and the potential tightening of US-China relations concerning Taiwan, geopolitical risks remain elevated. Although Europe’s dependence on raw materials from Russia is decreasing, a possible escalation of war or geopolitical tensions could disrupt the supply of energy and other raw materials. Furthermore, although China has abolished its exceptionally restrictive measures against the pandemic, the country’s sudden re-opening may result in the accelerated transmission of the virus and the deterioration of the global epidemiological situation, which could further hamper the functioning of important logistic hubs. Against such a backdrop, pressures on global supply chains could, after having eased in 2022 (Figure 6), grow stronger again, increasing inflationary pressures on a global scale, which could spill over to the economy of the euro area and Croatia.

An environment of long-standing high inflation could spur central banks to tighten their monetary policies even more aggressively, which would imply unfavourable effects on economic activity and increased risks to financial stability. Despite the deceleration of inflation in the euro area towards the end of 2022, primarily as a result of a drop in energy prices, core inflation still shows no sign of descending from its elevated level. Such trends could call for a more aggressive monetary policy approach, with further interest rate increases and central bank balance sheet reductions. Possible unexpected monetary policy tightening could trigger a stronger decline in the prices of financial assets, and possible forced sales would additionally reduce liquidity and deepen the fall of prices, thus aggravating the threats to financial stability.

In addition to the monetary domain, possible triggers for risk materialisation may also stem from the fiscal domain. Following the strong fiscal expansion during the pandemic, which resulted in a significant increase of public debt, a set of fiscal measures aimed at mitigating the effects of high inflation was introduced in response to the energy crisis. The deterioration of fiscal indicators could lead to the resurgence of the question of public debt sustainability in several large global economies. The US is close to reaching the public debt ceiling set by the Treasury, and a possible failure to reach a political consensus regarding the lifting of the debt limit could increase the US risk premium, which would lead to stress expansion on global financial markets, increase the caution of market participants, raise the risk premium and interest rates and thus create pressures on the financial stability on a global scale.

|

Figure 6 Trends in global trading conditions |

|

|

Notes: The global supply chain pressure index is shown in terms of standard deviations from the average value of the index, where higher values point to stronger global supply chain pressures. Euro area purchasing managers’ index is defined in relation to the preceding month, and if it takes a value above 50, economic activity is considered to be increasing. |

|

Source: Bloomberg. |

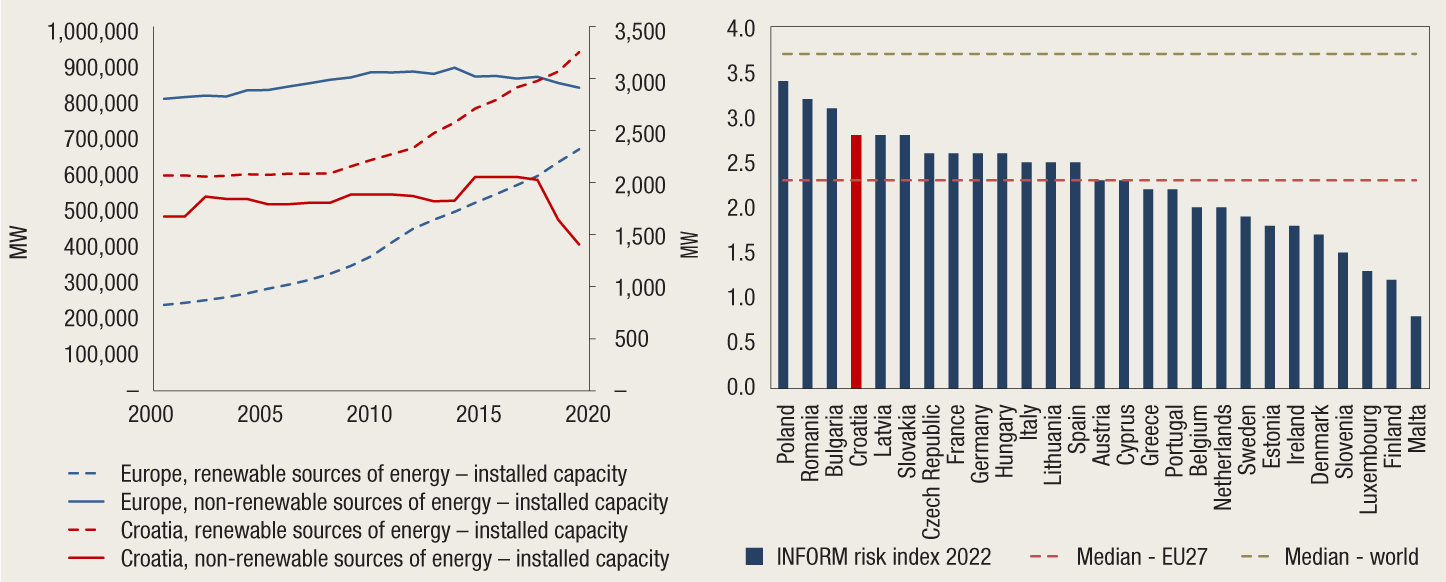

Climate changes could also trigger an increase of risks to financial stability. Although unfavourable climate events are picking up and thus stressing the need to accelerate the green transition, a deterioration of the corporate sector’s business environment could hinder investments in the green transition. In order to ensure operational continuity during the period of the sudden rise in the prices of energy and raw materials, some corporations from the energy sector in Croatia resorted to increasing their debt in 2022 (Figure 4) to finance their operational business (increasing reserves and purchasing energy products), and also to fund the energy sector’s green transition and increasing independence of fossil fuels (Figure 7). However, should a decline in demand reduce the volume of operations, the transition towards sustainable business of non-financial corporations could slow down, which could, in the longer term, have negative effects on future economic growth and the financial system.

|

Figure 7 Green transition and climate risk |

|

|

Notes: Installed capacity refers to the maximum net generating capacity of power plants in a given year. INFORM risk index represents the sensitivity of particular countries to human and natural disasters that may destabilise national civil protection capacities. The index encompasses three dimensions: hazard and exposure, vulnerability and lack of coping capacity; higher index values point to higher risk. The aggregate measure for the world and EU countries is calculated as the median of indices by countries. |

|

Source: European Commission, IMF and CNB calculations. |

3 Recent macroprudential activities

The upward phase of the financial cycle and the related increase of cyclical systemic risks continued in late 2022 despite the slowdown in economic growth resulting from the continued uncertainty caused by inflation, the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine. In response, the CNB decided to raise the announced countercyclical buffer rate to 1%. Furthermore, the regular biennial review of the required systemic risk buffer amount was carried out, and confirmed that structural risks and vulnerabilities remained moderately elevated, so that the aforementioned buffer rate was set to remain at the current level of 1.5%. In addition, the status of other systemically important credit institutions was confirmed for seven institutions and their capital buffer rates were adjusted.

3.1 The countercyclical capital buffer rate announced to increase from 0.5% to 1%

Amid a steady financial upturn and the associated increase in cyclical systemic risks, in December 2022, the CNB announced that it would raise the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 1%, effective as of 31 December 2023. In line with the announcement of August 2022, the decision builds on the previously announced rate increase from 0% to 0.5% as of 31 March 2023 to ensure a timely allocation of additional capital and thus enhance the resilience of banks in the event of adverse economic and financial scenarios materialising. In the first three quarters of 2022, the development of cyclical systemic risks was primarily driven by the accelerated residential real estate price increase coupled with the continued growth in housing loans and the further acceleration in lending to non-financial corporations, particularly those from the energy sector. The capital buffer increase will also provide the manoeuvring space needed by the CNB to support the operations and lending activity of banks in the event of systemic risks materialisation, as urged also by the European Central Bank and the European Systemic Risk Board. Increased capital buffers should not have any unfavourable effects on the cost and availability of bank lending as credit institutions are liquid and profitable and have accumulated substantial capital surpluses at system level.

3.2 Review of the systemic importance of credit institutions

Following its regular annual review, the CNB confirmed the status of seven previously identified other systemically important credit institutions and adjusted the capital buffer rates that these credit institutions will be required to maintain in 2023. The review was carried out in September 2022 on the basis of data from the end of 2021 in line with the guidelines of the European Banking Authority and the internal methodology. It is important to note that Addiko Bank d.d., whose summary score of systemic importance was in this review cycle for the first time below the threshold, was identified as an O-SII based on expert judgement supported by individual mandatory and additional indicators of systemic importance. Capital buffer rates for identified O-SIIs have been calibrated in line with the CNB’s internal methodology, while the rates that the O-SIIs will be required to maintain in 2023 take into account the legal limitations arising from the status of the parent credit institution in the EU (Table 1).

Table 1 O-SIIs in the Republic of Croatia

* Taking into account the status of the parent O-SII or G-SII in the EU, where applicable.

| O-SII | Systemic importance score | Buffer rate set for O-SII as of 1 January 2023 | Buffer rate to be maintained by the O-SII as of 1 January 2023* |

| Zagrebačka banka d.d., Zagreb | 2889 | 2.0% | 2.0% |

| Privredna banka Zagreb d.d., Zagreb | 2298 | 2.0% | 1.75% |

| Erste&Steiermärkische Bank d.d., Rijeka | 2006 | 2.0% | 2.0% |

| Raiffeisenbank Austria d.d., Zagreb | 878 | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| OTP banka Hrvatska d.d., Split | 700 | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Hrvatska poštanska banka d.d., Zagreb | 302 | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Addiko Bank d.d., Zagreb | 242 | 0.5% | 0.5% |

Source: CNB.

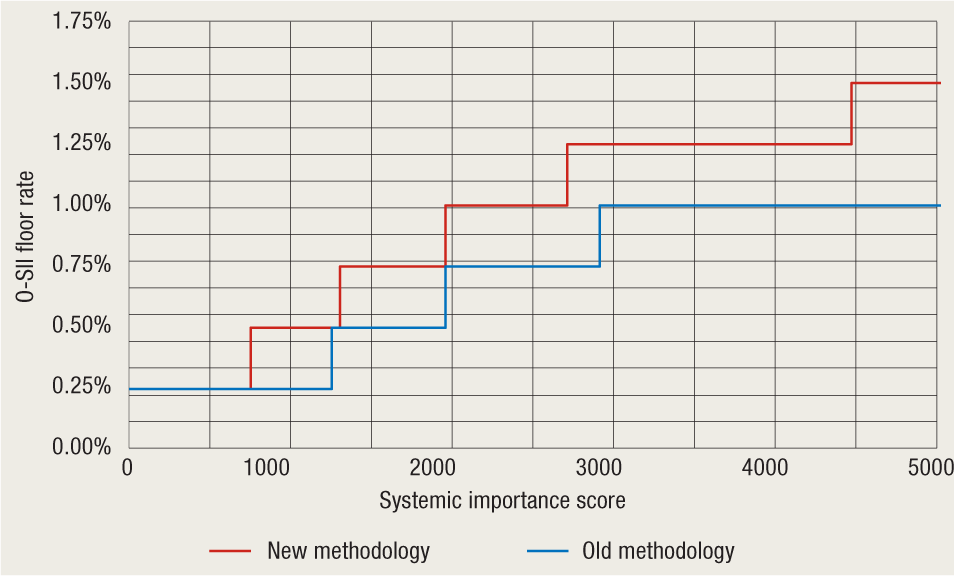

Box 2 Review of the ECB’s floor methodology for other systemically important institutions

The regulatory framework of the European Central Bank (hereinafter referred to as ‘the ECB’) prescribes minimum buffer rates (the so-called floor methodology) for identified other systemically important institutions (hereinafter referred to as ‘O-SIIs’) in all member countries of the single supervisory mechanism (hereinafter referred to as ‘the SSM’). The framework was introduced in 2016, and following a period of adjustment that was extended due to the COVID-19 pandemic, its obligatory application entered into force in early 2022. Under the aforementioned methodology, all O-SIIs within the banking union are classified into four categories, or ‘buckets’, according to their systemic importance score, whereby each bucket is associated with a minimum buffer rate, or ‘floor’, starting from 0.25% for the lowest to 1% for the highest bucket (Figure 8). The aim was to ensure an initial harmonisation of floors that O-SIIs are required to maintain in particular SSM jurisdictions.

In 2019, the ECB revised its methodology for setting floors; this will, due to the two-year delay caused by the pandemic, begin to apply on 1 January 2024. The number of buckets into which O-SIIs are allocated has been increased from four to six, with a faster progression of the O-SII buffer rate and an increase of the floor level for O-SIIs in the highest bucket from 1% to 1.5%. The revised methodology is aimed at further reducing the heterogeneity of banking union O-SII buffer rates in the lower part of the range, while a higher floor level set for the largest O-SIIs will enhance their resilience. According to the data for the end of 2022, most O-SIIs in the banking union meet new floor requirements, while the application of the new methodology will call for the adjustment of seven O-SIIs in four SSM member states in terms of a buffer increase of 0.25 or 0.50 basis points. All O-SIIs in Croatia comply with the new methodology as their buffer rates are above the floor prescribed for their respective bucket.

Figure 8 Comparison of floor levels for O-SIIs under the ECB's old and new methodology

Source: ECB.

3.3 Continued application of the structural systemic risk buffer

As part of its regular biennial review of the structural systemic risk buffer, the CNB decided to maintain the aforementioned capital buffer rate at a level of 1.5% of the total risk exposure. Based on an analysis of structural vulnerabilities and systemic risks in the domestic economy, and building on the previously prescribed capital buffer rate requirement of 1.5%[6], in late December, the CNB announced that it would continue to apply the rate set earlier. The structural imbalances and systemic risk exposure of the domestic economy, which, as a small and open economy, is highly susceptible to the spillover of unfavourable influences from the international environment, remained moderately elevated over the past two years. Particularly noteworthy are a relatively high public debt level, the high exposure of the banking sector to the government and the persisting imbalances in the labour market reflected in the very low rates of labour force participation and unfavourable demographic and migration trends that limit the potential for economic growth. The circumstances referred to above support the need to maintain a structural systemic risk buffer rate at its current level of 1.5%.

3.4 Warning of the European Systemic Risk Board

In late September 2022, the European Systemic Risk Board issued a warning on vulnerabilities in the financial system of the European Union. ESRB warns that risks related to the EU financial system have grown along with the probability of materialisation of a tail-risk scenario related to geopolitical developments, which is why it is essential to work on preserving and enhancing the resilience of the European financial sector so that it may continue to support the real economy if and when risks to financial stability materialise. Credit institutions can act as a first line of defence by adjusting their provisioning practices and capital planning to properly account for expected and unexpected losses associated with current risks, while the role of microprudential and macroprudential regulators is to support further the resilience of credit institution using instruments from their area of competence. The warning particularly stresses that the preservation or further build-up of capital buffers not only supports credit institutions’ resilience, but also provides authorities with more room to release such buffers if and when risks materialise, thus supporting the credit institutions’ operations and economic recovery. However, decisions on macroprudential policy and possible increases of capital requirements should be made bearing in mind the specific circumstances of each member state to reduce the risk of procyclicality. Finally, the ESRB stresses the importance of addressing risks to financial stability stemming from beyond the banking sector.

As well as the ESRB, in the statement of the Governing Council of 2 November 2022 the ECB also warned against growing systemic risks and the need to build up adequate macroprudential capital buffers. CNB analyses also point to elevated risks to financial stability (Chapters 1 and 2), so that its macroprudential policy continues to be directed at enhancing the resilience of credit institutions (see items 3.1 and 3.3).

3.5 Implementation of macroprudential policy in other European Economic Area countries

In the last quarter of 2022, a smaller number of EEA member countries tightened their measures aimed at mitigating cyclical systemic risks and risks associated with the real estate market.

Spurred by growing risks associated with the intensified increase in banks’ loan portfolio, Estonia announced that it would raise its countercyclical capital buffer rate from the currently applicable 1% to 1.5% as of December 2023. The aforementioned buffer rate will also be increased in Ireland, from the previously announced 0.5% as of June 2023 to 1% as of the end of November 2023, which is one of the steps towards the targeted buffer rate level of 1.5%. France also announced that it would lift the countercyclical capital buffer rate from 0.5% applicable as of June 2023 to 1% applicable as of January 2024 to further enhance the solvency of credit institutions. Romania, too, decided to raise the rate from the currently applicable 0.5% to 1%, effective as of the end of October 2023 due to continuous macroeconomic imbalances and increased risks associated with household incomes and corporate profitability. Slovenia and Cyprus activated the countercyclical capital buffer rate for the first time. Slovenia’s decision to announce the lifting of the rate to 0.5% as of December 2023 was driven by increasing cyclical risks led by the strong growth in residential real estate prices and total loans to the private non-financial sector. Cyprus will raise its countercyclical buffer rate from 0% to 0.5% as of the end of November 2023 to ensure the stability of bank lending to the real economy over the future, potentially riskier, period.

Following a review of currently applicable systemic risk buffer rates, Austria decided to introduce minor changes. Among other things, certain credit institutions are required, on an individual basis, to gradually increase their rates over the course of 2023. The maximum rate has been set to remain at 1%, and the buffer is applicable to all exposures.

As of January 2023, Ireland eased the measures directed at housing loan beneficiaries, bearing in mind the decline in the affordability of residential real estate resulting from the continuous increase in their prices amid limited supply. The minimum loan-to-value (LTV) ratio has been lifted from 80% to 90% for purchasers of second and subsequent properties, while for first-time buyers and buy-to-let buyers the ratio will remain at 90% and 70%, respectively. The loan-to-income (LTI) ratio for first-time buyers has been eased from the previously applicable 3.5%, a level applied to all other housing loan beneficiaries, to 4%.

Table 2 Overview of macroprudential measures in EEA countries and the United Kingdom

Notes: The listed measures are in line with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (CRR) and Directive 2013/36/EU on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (CRD IV). The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of Abbreviations at the end of the publication. Green indicates measures that have been added since the last version of the table. Light red indicates measures which countries have released in response to the crisis triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and which were not re-applied as at 1 February 2023. Disclaimer: of which the CNB is aware..

Sources: ESRB, CNB and notifications from central banks and websites of central banks as at 01 February 2023.

For details, see:

https://www.esrb.europa.eu/national_policy/html/index.en.html and https://www.esrb.europa.eu/home/coronavirus/html/index.en.html.

Table 3 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

Notes: The definitions of abbreviations are provided in the List of Abbreviations at the end of the publication.

Source: CNB.

-

https://www.hnb.hr/documents/20182/2042017/ep26092017_preporuka.pdf ↑

-

In the fourth quarter of 2022, the Government of the Republic of Croatia proposed to the Parliament the Law on Excess Profit Tax, i.e., it announced the introduction of the excess profit tax. The tax is envisaged as a redistributive measure by which large corporations that generated additional profit on account of growing inflation will contribute to the mitigation of negative consequences of price growth to the most vulnerable citizens (for example, through the funding of aid for particularly vulnerable households with a view to mitigating the effects of high prices of energy and other products). According to the estimates of the Ministry of Finance, some 192 corporations will be subject to excess profit tax, which will generate around HRK 1.5 bn of revenues for the government.

Excess profit tax is calculated according to the following formula: excess profit tax = (gross earnings2022 –1.2xgrossearnings_average(2018-2021)) x 33%, for corporations which, in 2022, generated more than HRK 300 million in profits. ↑

-

https://taxfoundation.org/windfall-tax-europe/ ↑

-

For example, the introduction of the bank asset tax in Hungary resulted in the spillover of the tax burden to households via interest rate increase (Capelle-Blancard, G., and O. Havrylchyk (2007): Incidence of Bank Levy and Bank Market Power, Review of Finance, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 1023–1046, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfw069) ↑

-

In the Bank Lending Survey, the banks have continuously, since 2012, stated that the competition among banks was one of the factors leading to the easing of financing conditions in Croatia (https://www.hnb.hr/en/statistics/statistical-surveys/bank-lending-survey). ↑

-

Pursuant to the Decision on the application of the systemic risk buffer of December 2020. ↑