Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 21

Introductory remarks

The macroprudential diagnostic process consists of assessing any macroeconomic and financial relations and developments that might result in the disruption of financial stability. In the process, individual signals indicating an increased level of risk are detected, according to calibrations using statistical methods, regulatory standards or expert estimates. They are then synthesised in a risk map indicating the level and dynamics of vulnerability, thus facilitating the identification of systemic risk, which includes the definition of its nature (structural or cyclical), location (segment of the system in which it is developing) and source (for instance, identifying whether the risk reflects disruptions on the demand or on the supply side). With regard to such diagnostics, instruments are optimised and the intensity of measures is calibrated in order to address the risks as efficiently as possible, reduce regulatory risk, including that of inaction bias, and minimise potential negative spillovers to other sectors as well as unexpected cross-border effects. What is more, market participants are thus informed of identified vulnerabilities and risks that might materialise and jeopardise financial stability.

Glossary

Financial stability is characterised by the smooth and efficient functioning of the entire financial system with regard to the financial resource allocation process, risk assessment and management, payments execution, resilience of the financial system to sudden shocks and its contribution to sustainable long-term economic growth.

Systemic risk is defined as the risk of events that might, through various channels, disrupt the provision of financial services or result in a surge in their prices, as well as jeopardise the smooth functioning of a larger part of the financial system, thus negatively affecting real economic activity.

Vulnerability, within the context of financial stability, refers to the structural characteristics or weaknesses of the domestic economy that may either make it less resilient to possible shocks or intensify the negative consequences of such shocks. This publication analyses risks related to events or developments that, if materialised, may result in the disruption of financial stability. For instance, due to the high ratios of public and external debt to GDP and the consequentially high demand for debt (re)financing, Croatia is very vulnerable to possible changes in financial conditions and is exposed to interest rate and exchange rate change risks.

Macroprudential policy measures imply the use of economic policy instruments that, depending on the specific features of risk and the characteristics of its materialisation, may be standard macroprudential policy measures. In addition, monetary, microprudential, fiscal and other policy measures may also be used for macroprudential purposes, if necessary. Because the evolution of systemic risk and its consequences, despite certain regularities, may be difficult to predict in all of their manifestations, the successful safeguarding of financial stability requires not only cross-institutional cooperation within the field of their coordination but also the development of additional measures and approaches, when needed.

1 Identification of systemic risks

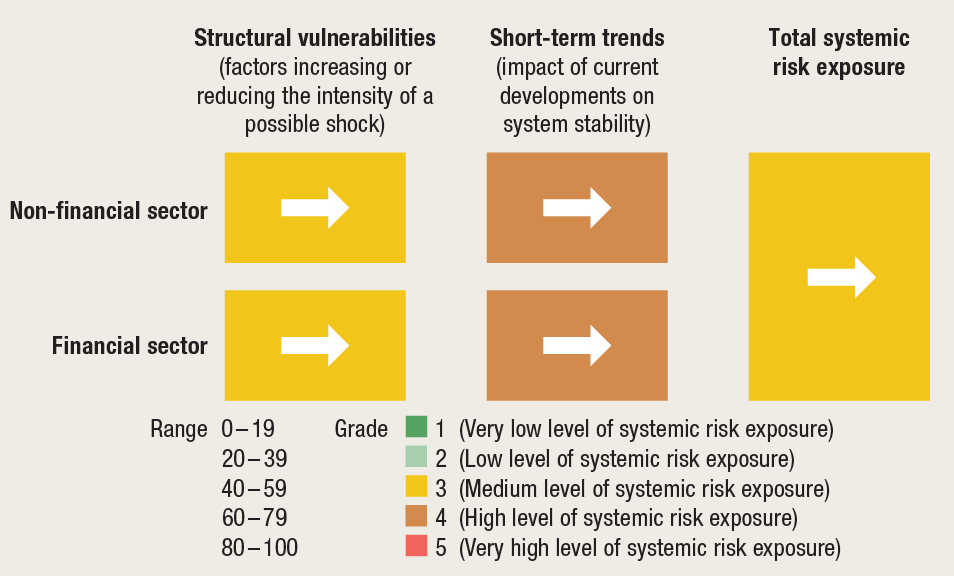

Risks to the financial system of the Republic of Croatia remained broadly unchanged in the third quarter of 2023 with a slightly more unfavourable medium-term outlook (Figure 1). High inflation remains one of the main risks, while the beginning of the third quarter saw signs of economic slowdown in the euro area, reflected in lower high-frequency indicators for Croatia. Despite the tightening of financing conditions, lending activity remained quite robust, and thanks to high liquidity and the widening in the interest rate spread, bank profitability reached decade highs. However, in the medium term, bank performance could be negatively affected by the deterioration in asset quality related to interest rate increase and economic slowdown. Growing inflationary pressures have thus far affected corporate performance positively, but in the upcoming period, their business results could be influenced by growing debt servicing costs and uncertain economic developments. Household resilience is supported by the strong labour market and real income recovery. Upward trends in the prices on the residential real estate market continued, but were accompanied by a noticeable slowdown in activity relative to the year before, which could point to growing risks of cycle reversal.

Figure 1 Risk map, third quarter of 2023

Note: The arrows indicate changes from the risk map in the second quarter of 2023 published in Macroprudential Diagnostics No. 20 (July 2023).

Source: CNB.

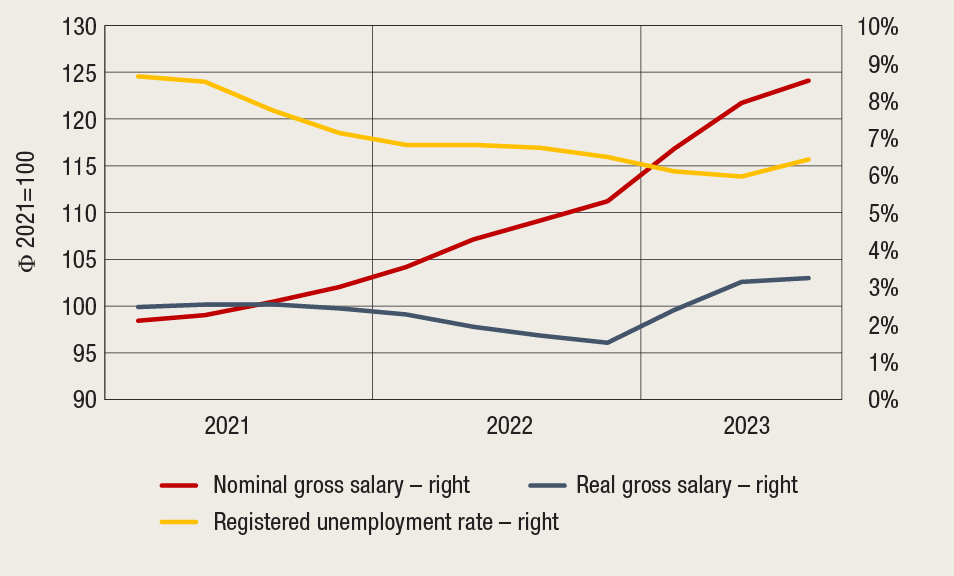

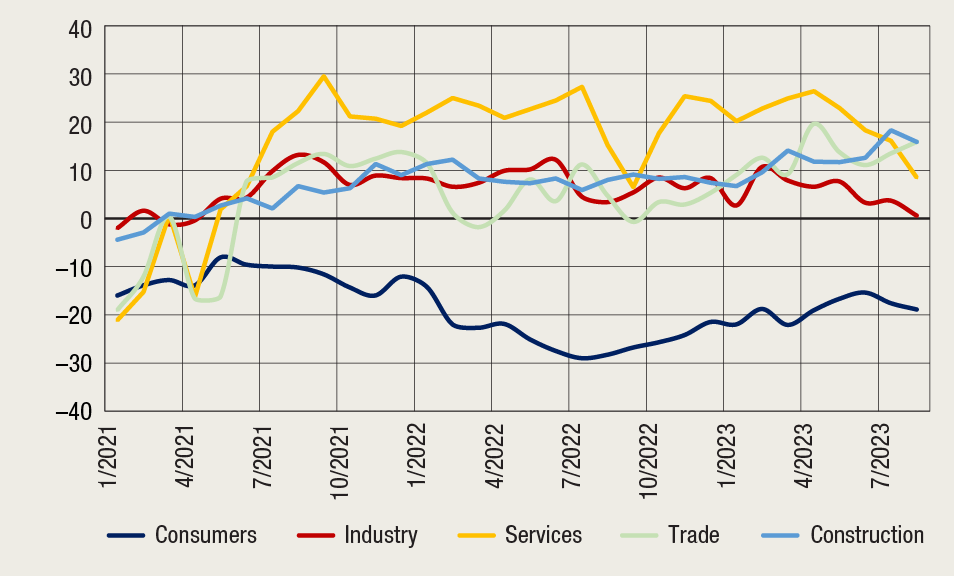

Following a relatively strong growth in the first half of the year, at the beginning of the third quarter, signs of a slowdown in economic activity became noticeable in Croatia. Favourable developments in the first half of the year were mainly driven by growing personal consumption and exports of services supported by a strong labour market, real income recovery and favourable tourism performance. However, high-frequency indicators available for the beginning of the third quarter point to a drop in activity. Trade stagnated from the second quarter, while industry and physical indicators for tourism contracted; business and consumer confidence indices show a noticeable decline in optimism (Figure 3). Economic activity is unfavourably affected by the stagnation of the EU economy, particularly that of Croatia’s main trading partners, Germany and Italy, as the third quarter was marked by poor survey indicators of activity in the European economy, which reinforced negative risks for economic growth.

Figure 2 Favourable indicators from the labour market have thus far been supported by favourable economic results...

Note: Data for the third quarter refer to July.

Sources: CBS, CES and CNB calculations (seasonally adjusted by the CNB).

Figure 3 ...but the deteriorated confidence of domestic corporations and consumers points to elevated uncertainty

Source: European Commission.

Following a temporary pick-up in August, inflation on the domestic market, measured by the HICP, slowed down to 7.3% in September (from 8.4% in August). This is a result of a lower contribution from industrial product and service prices, and, to a lesser extent, food prices, while core inflation, which covers only the price evolution of industrial products and services, dropped from 9.1% to 7.1%. Current inflationary pressures, which were particularly pronounced during the main tourist season, also decreased in September. According to the CNB's macroeconomic projections[1], the deceleration of annual inflation, which began in late 2022, should continue.

Total loans continued to grow relatively strongly. Observed on an annual basis, growth in household loans rose to 7.7% in August (transaction-based), with the two-digit increase in housing loans (10.1% in August) reflecting the new round of government subsidy allocation amid noticeably higher residential property prices. At the same time, general-purpose cash loans, whose growth has been accelerating continuously in 2023, increased substantially (to 7.4% in August) under the influence of growing consumer confidence. In the segment of non-financial corporations, lending was subdued over the past months, which slowed down their annual rate of growth to 10.8% in August.

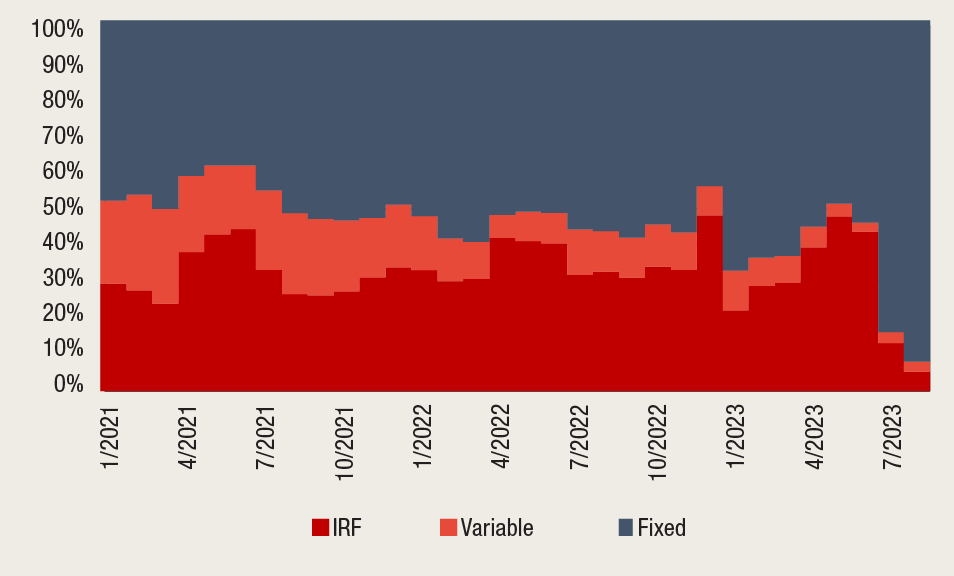

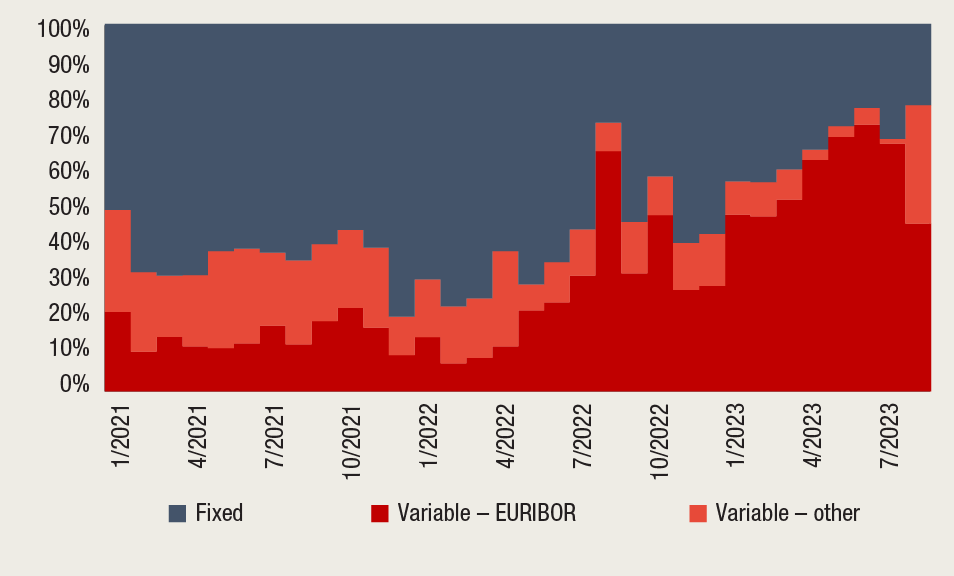

Increasing portfolio segmentation is noticeable in the structure of newly-granted loans according to interest rate variability. In contrast to corporate loans, which have lately mostly been granted at a variable interest rate linked to the EURIBOR, household loans are mostly granted at fixed interest rates (Figures 4 and 5). This is due to the relatively low level of the legally prescribed cap on maximum interest rates on housing loans with variable interest rates compared to current reference interest rates, which redirected the supply of housing loans towards fixed rate loans, to which a significantly higher cap is applied. Some banks also started to offer more general-purpose cash loans at a variable interest rate linked to the EURIBOR, although most such loans are still granted at fixed interest rates.

Figure 4 Newly-granted household loans, pure new loans

Note: IRF – period of initial interest rate fixing.

Source: CNB.

Figure 5 Newly-granted corporate loans, pure new loans

Note: IRF – period of initial interest rate fixing.

Source: CNB.

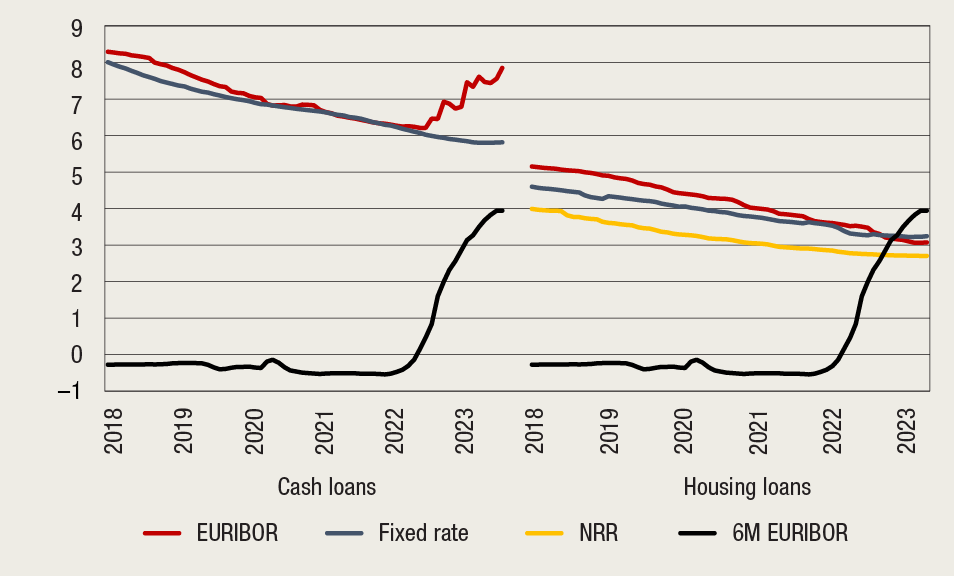

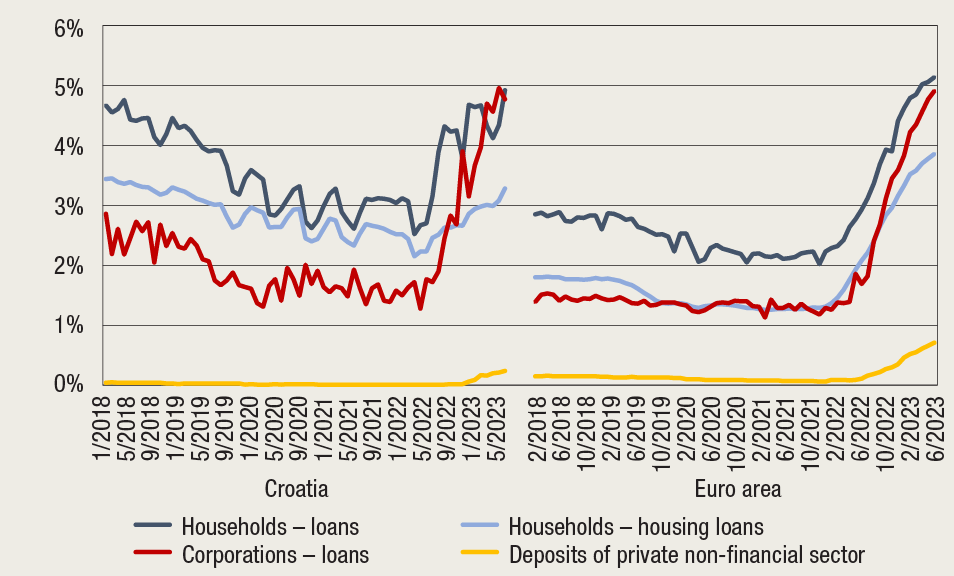

The ECB's cycle of key interest rate increases has largely been passed to the financing costs of the private non-financial sector, with the pass-through being more pronounced in corporate lending than in household lending. The interest rate on pure new loans to corporations increased by 344 basis points from June 2022 and reached 5.14% in late August 2023. In the household segment, the interest rate on pure new general-purpose cash loans increased by 73 basis points, standing at 6.05% in August, while for housing loans, it grew by 131 basis point, reaching 3.55%. The intensity of the increase in interest rates on housing loans in Croatia was somewhat dampened by the government housing loans subsidy programme, within which housing loans are usually granted at an interest rate lower than the market average.

At the same time, interest rates on existing loans are increasing due to the granting of new loans at higher interest rates and the adjustment of repayments of loans with variable interest rates to increasing reference parameters. While interest rate increase is pronounced for corporate loans, households have, until now, been protected from an increasing debt repayment burden by a high share of loans with fixed interest rates and the legally prescribed cap on the maximum permitted variable interest rate on housing loans, so that in those loan segments costs did not increase for debtors. Nevertheless, for a very small portion of household loans (around 1.7%), i.e., for cash loans granted at a variable interest rate linked to the EURIBOR, the average interest rate on existing loans rose by almost 200 basis points (Figure 8) in line with the increase in the EURIBOR. Even though, owing to the favourable labour market situation, credit risk is still not increasing noticeably in such loans, a relatively strong transmission of changes in market interest rates is a sign of possible medium-term developments in other consumer loan types as well, particularly if the legally prescribed cap on the maximum variable interest rate is raised under the influence of a gradual rise in deposit interest rates and the NRR.

Figure 6 Interest rates on the balances of loans

Source: CNB.

In the first half of the year, residential property prices continued to grow strongly despite slower market activity and tighter financing conditions. In the second quarter of 2023, residential property prices grew by 3.5% on a quarterly basis and by 13.7% relative to the same period last year. Croatia thus ranks among the EU countries with the highest price growth, while in a large number of member states, residential property prices have been declining for some time now. High prices are still supported by the housing loans subsidy programme, which, according to announcements from the government of Croatia, was implemented in 2023 for the last time. Still, the number of purchase and sale transactions including residential real estate shrank in the first half of 2023 by 12% in annual terms, in line with the developments in most EU countries. The weakening of foreign demand was particularly pronounced: in the first half of 2023, the share of transactions involving non-residents fell, both in number and total value, to the lowest level recorded in the past two years. Although this suggests that the price cycle could reverse, risks to financial stability linked with the residential real estate market are currently mitigated by the significantly lower reliance on borrowing compared with the real estate cycle in the middle of the past decade.

The banking system remained highly capitalised in the first half of 2023, with a capital ratio of 23.2% and a surplus above the regulatory requirements of 7.7 percentage points. A slight decrease in the total capital ratio is a result of own funds decrease due to dividend payments, while risk-weighted assets grew under the influence of stronger lending activity despite the decline of the average risk weight. The liquidity of credit institutions measured by the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) at the end of July reached a historical high of 243%, while the NSFR stood at 173.3% at the end of June, which points to the exceptionally high liquidity and stability of sources of financing.

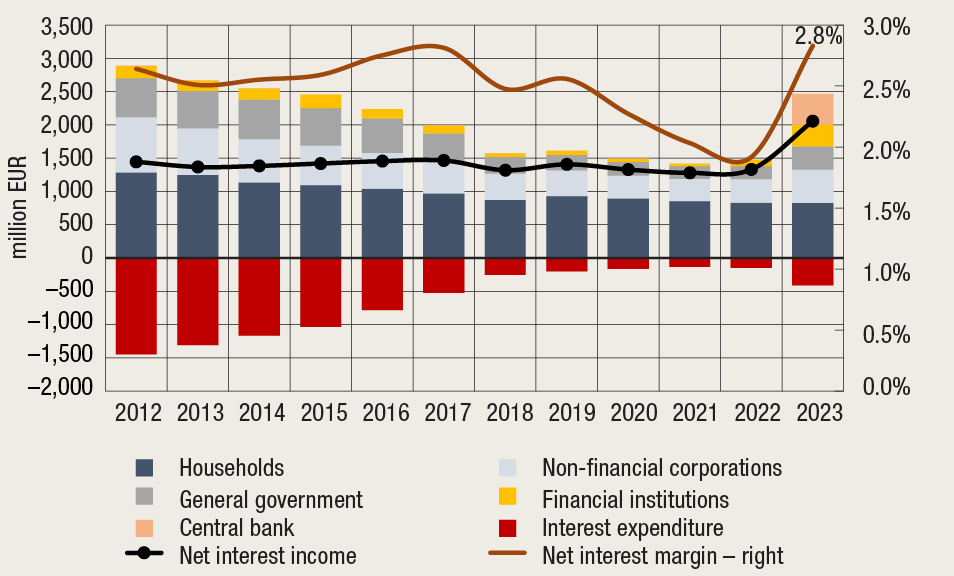

Bank profitability is growing strongly owing to the increase in net interest income (see Box 1), spurred by growing interest margins and a high share of assets sensitive to interest rate changes. Bank profitability was also favourably affected by the release of provisions for credit losses created over the past years amid elevated uncertainty driven by unfavourable economic effects of the global pandemic. In contrast, administrative expenses grew in 2023 under the influence of high inflation (by 10% on average), both in the segment of employee expenses and other administrative expenses. In the first half of 2023, banks generated a profit of EUR 703.8m, which is almost equal to last year’s net profit. Consequently, key returns indicators grew substantially from the end of 2022: return on assets (ROA) rose from 1.0% to 1.9% and return on equity (ROE) increased from 8.2% to 16.8%. However, in the medium and longer term, financing costs could increase further amid the stronger transmission of monetary policy to domestic deposit interest rates which still lag behind other euro area countries, particularly in the segment of overnight deposits. In addition, the portfolio of long-term securities and fixed-yield loans accumulated during a period of low interest rates could, for a while, limit the growth in income, and the deterioration of the loan portfolio could drive impairments upwards.

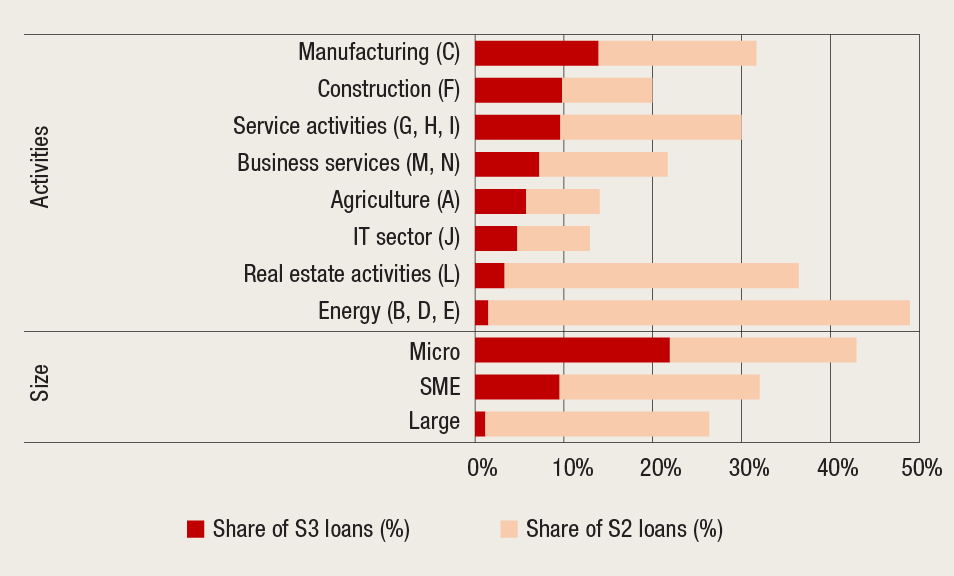

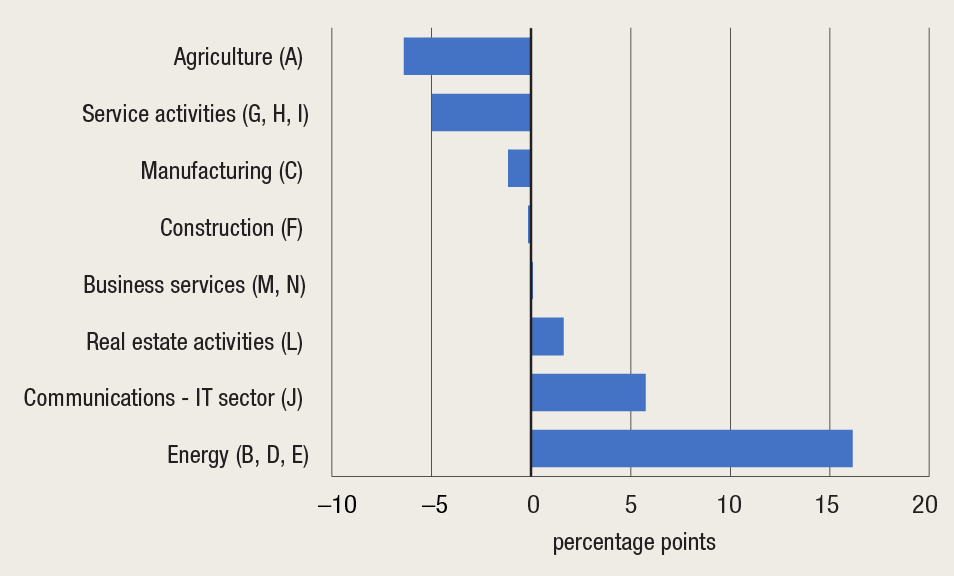

Although the nominal amount of non-performing loans to the private non-financial sector continues to decline, certain early signs pointing to the need for caution arose. Specifically, the share of stage 2 loans in the corporate sector increased from 20.3% in March to 23.5% in June, primarily as a result of the reclassification of loans in the energy sector (stage 2 loans in that sector accounted for as much as 47% at the end of July; Figure 7), which exceeded the decline of stage 2 loans in other activities, such as service activities, where the level of such loans increased substantially during the pandemic (Figure 8). Rising financing costs could, against the backdrop of subdued demand, have unfavourable effects on corporate performance and lead to deterioration in asset quality, which has been relatively favourable over the past years despite the challenging operating conditions during the pandemic and the energy crisis. A possible deterioration in the economic outlook could, in the context of higher interest rates and difficult access to sources of financing, increase the cost of impairments, i.e. credit portfolio losses.

Figure 7 Loan quality in the corporate sector is relatively heterogeneous

Source: CNB.

Figure 8 Change in the share of stage 2 loans according to activity, 31 June 2023 relative to 31 December 2022

Source: CNB.

Banks should use their currently high profitability to improve their efficiency and increase their capital position to prepare better for potential future losses. The currently favourable environment offers a good starting point for intensifying efforts aimed at improving efficiency and cutting costs, which would enhance the banks’ competitiveness amid rapidly-changing financial conditions and challenges linked with applied technological innovations.

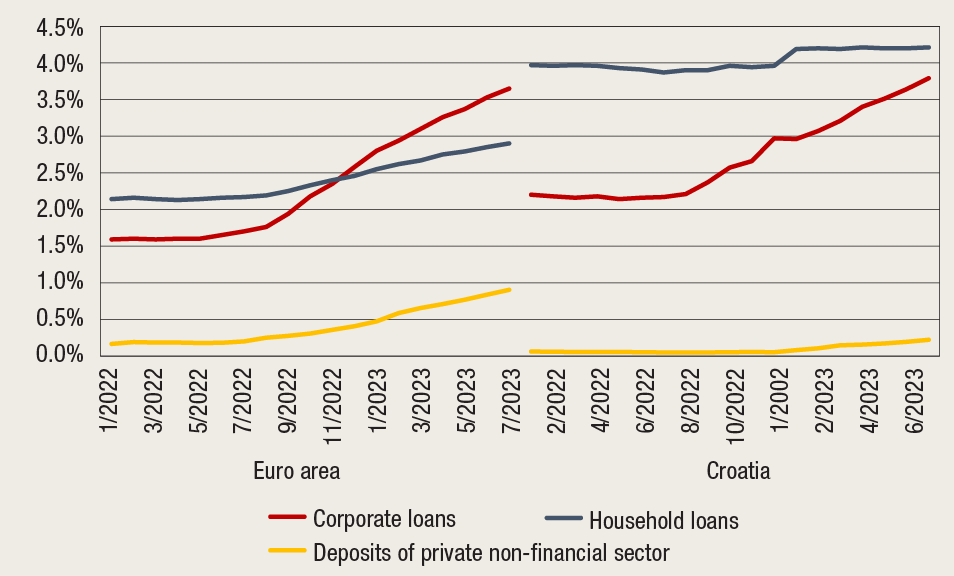

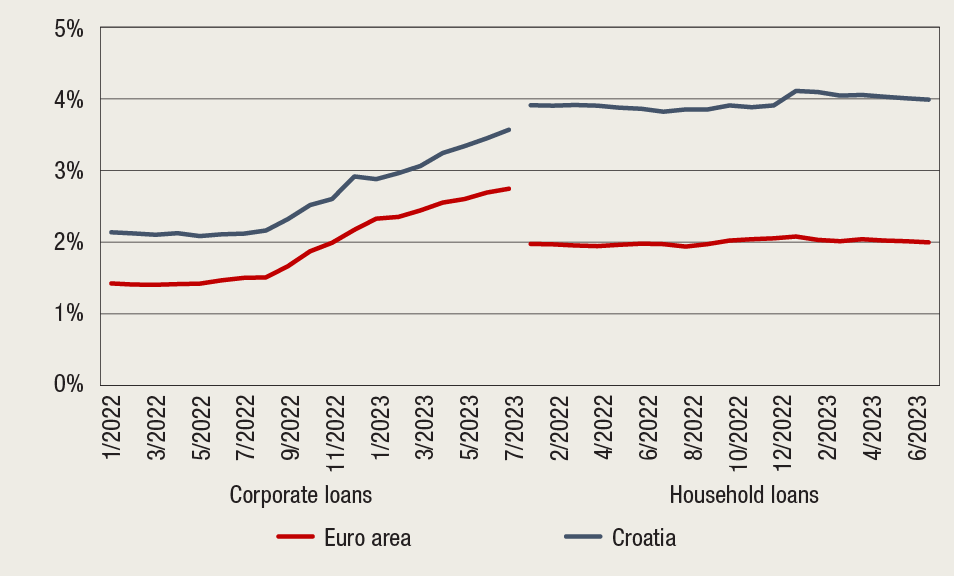

Box 1 Monetary policy tightening amplifies bank profitability growth

The strong growth in interest rates, coupled with increased lending, has had a considerable positive effect on the developments in bank profitability. Since spring last year, interest rates have been rising in Europe at a pace unparalleled for decades. To battle inflation, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised its key interest rates by a total of 450 basis points in ten consecutive meetings in the period from July 2022 to mid-September 2023. This sudden and strong departure from a low interest rate environment enabled domestic banks to strengthen their net interest margin owing to the structure of their assets and liabilities. Net interest margin is the key profitability ratio used to measure the difference between interest income generated by lending and investing in financial instruments and interest expenditures resulting from bank borrowing compared to average interest-bearing assets. Since lending interest rates on new (Figure 1) and existing loans (Figure 2) grew faster than interest rates on deposits, the interest rate spread, i.e., the average interest rate on the balances of loans relative to the average deposit rate, has been continuously increasing over the past year, particularly in corporate lending (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Lending and deposit rates, new business

Figure 2 Lending and deposit rates, balances

Figure 3 Interest rate spread, balances

Note: The average interest rate on deposits is the volume-weighted average of interest rates on time, sight and overnight deposits.

Source: ECB.

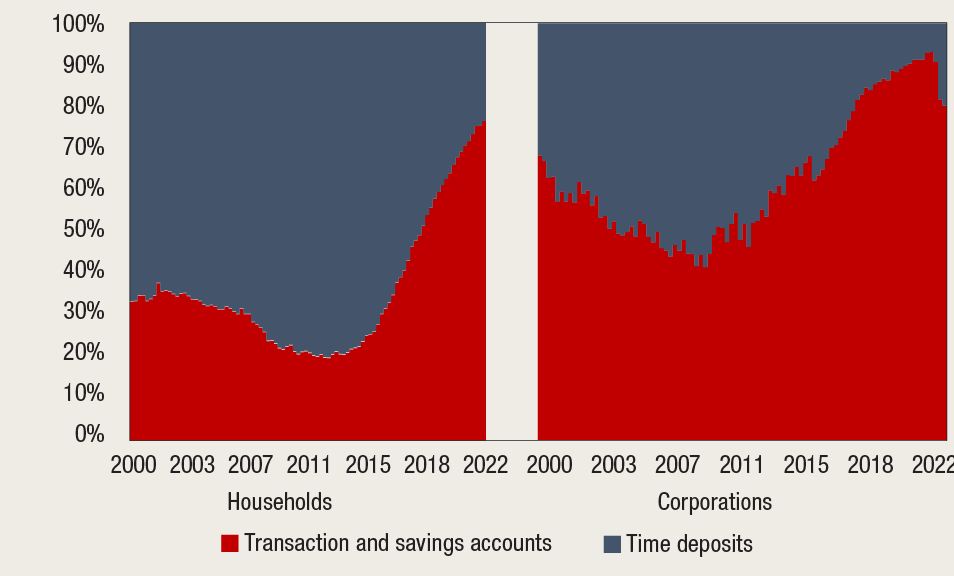

Even though interest rates on new time deposits of corporations and households in Croatia have grown since the beginning of the monetary policy tightening cycle, interest rates on overnight transaction deposits still lag behind. For now, interest rate sensitivity is most pronounced in new time deposits of non-financial corporations, which are more prone to switch to alternative investments with higher yields. Corporations have already transferred a portion of funds from overnight transaction accounts to time deposits (Figure 7). Changes in the structure of household deposits have thus far been limited; the structure is still dominated by transaction deposits, the behaviour of which still displays price inelasticity in current conditions, although the issue of a “public” bond in March this year triggered an outflow of a portion of deposits in demand for higher yields.

At the same time, interest rates on new loans (particularly in the corporate sector) increased at a faster pace than interest rates on deposits. Interest rates on outstanding corporate loans also grew strongly due to the large share of variable-rate loans with shorter maturities, which enables faster adjustment and higher interest rate spread. In contrast, interest rates on outstanding household loans still have not increased, due to the relatively long average maturity and the high share of fixed interest rate in loans, the dominance of the NRR in the structure of variable interest rates and the currently very restrictive cap on the maximum variable interest rate on housing loans.

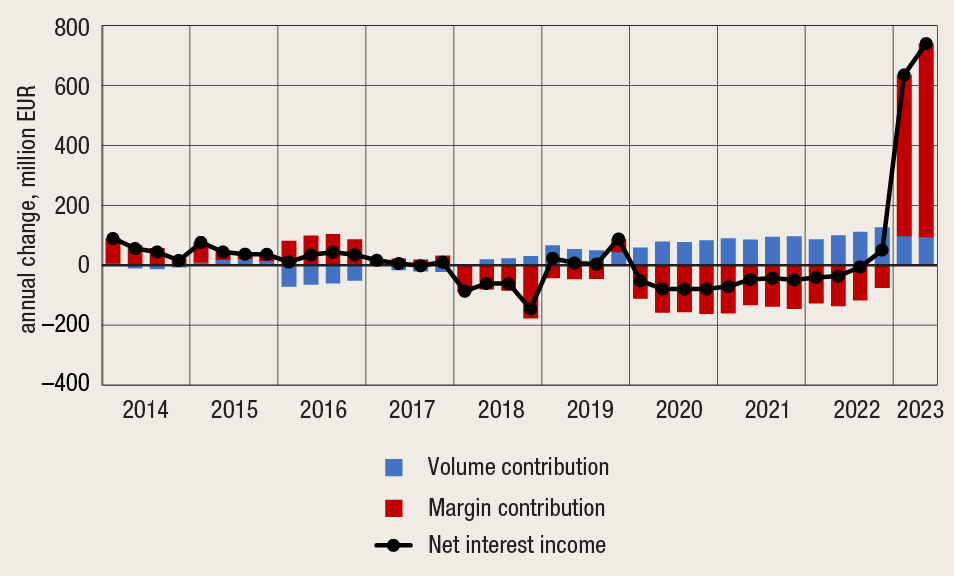

Net interest income is the most significant source of income of Croatian banks (accounting for over two thirds of income), and as a result of the increase in the interest rate spread in 2023, it grew considerably, reaching decade highs (Figure 4). Net interest income can change due not only to changes in new lending (volume effect) but also to an increase in the interest rate spread (margin effect, i.e., net interest margin), and Figure 5 shows that the dominant contribution to the change of net interest income in 2023 comes from margin growth. In contrast, over the past years, margins shrank, and banks maintained their net interest incomes by increasing the volumes of new loans.

Figure 4 Net interest income and net interest margin

Figure 5 Contribution to the annual change in net interest income

Notes: Net interest margin (NIM) is calculated as the ratio of interest income (assets) reduced by interest expenditures (liabilities) and divided by income from assets. In Figure 4, the calculation was made using the Marshall-Edgeworth (M-E) type decomposition, which divides annual change into margin effect (loan price change) and volume effect, with an equal division of combined effect: \(\Delta NIM = Margin + Volume, i.e. p_1 * q_1-p_0 * q_0= Margin + Volume\),

where, \(Margin =\left(p_1-p_0\right) \frac{q_1+q_0}{2}, and Volume =\left(q_1-q_0\right) \frac{p_1+p_0}{2}\)

Source: CNB.

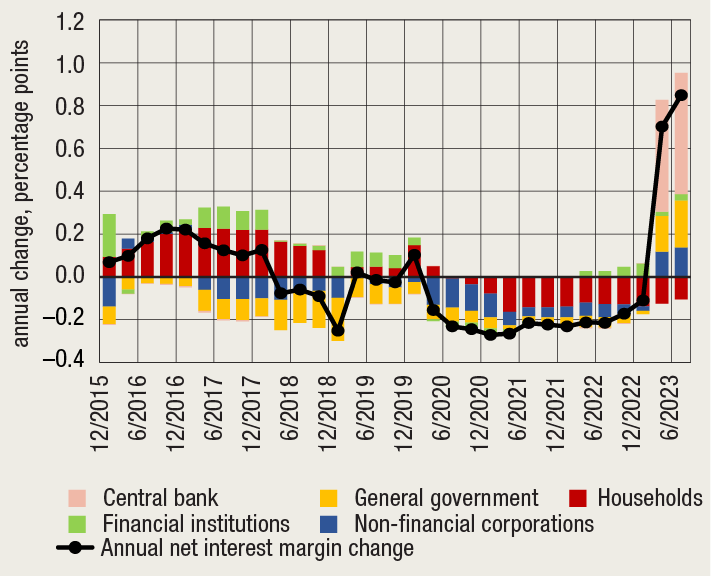

The increase in net interest income was generated by business operations with all sectors except households (Figure 6.a), most notably by the overnight deposits with the central bank[2]. Broken down by type of instrument, in addition to loans and deposits with the CNB, the increase in interest income was significantly driven by other interest-bearing assets, with equal contributions from income from debt securities and from deposits with foreign financial institutions (Figure 6.b).

Income from overnight deposits increased strongly due to the relatively high level of free liquidity with very short maturity. Against such a backdrop, interest income reacts rapidly to monetary policy tightening (i.e., to the lifting of key interest rates), in contrast to other assets (such as loans), in relation to which income grows significantly slower, depending on the share of fixed interest rates and reference parameters in the portion of assets with a variable rate and legally prescribed caps and frequency of interest rate change (e.g., only a couple of times per year).

Figure 6 Net interest margin change

| a. Contribution by sector | b. Contribution by instrument |

|

|

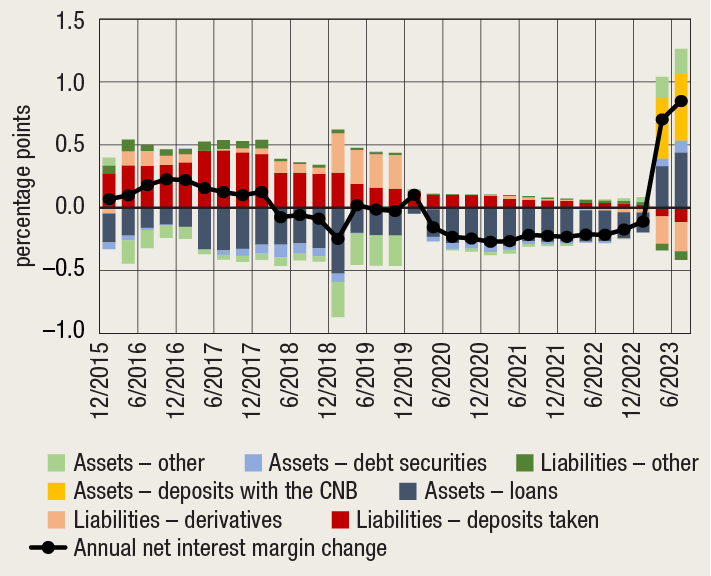

| Source: CNB. |

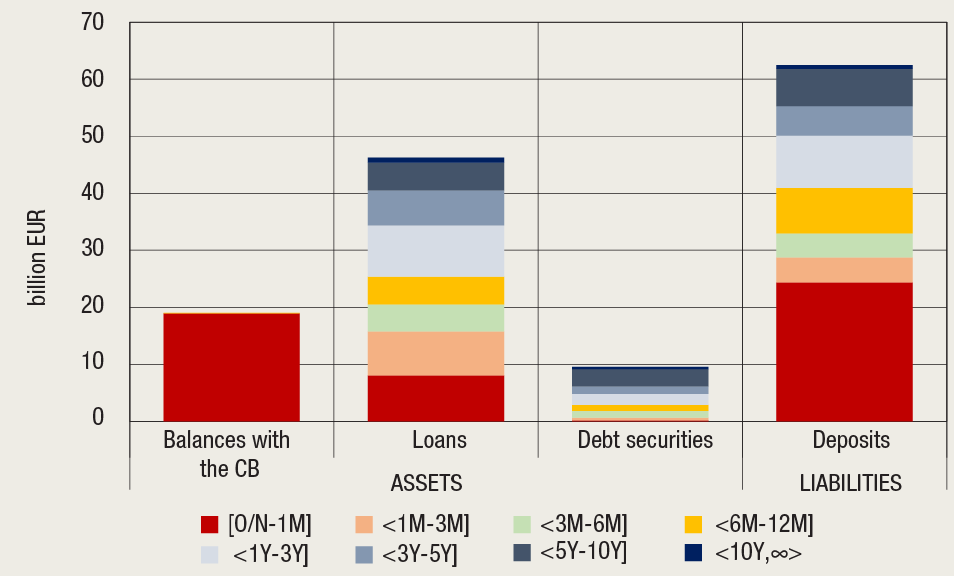

The currently strong increase in profitability is probably temporary. Specifically, domestic banks hold their assets in a high share of fixed-rate long term instruments (loans and debt securities), and tend to grant new loans at fixed interest rates, which limits the possibility of a passthrough of higher interest rates on the asset side of the balance sheet. Such loans and investments are mostly financed from deposits of the private non-financial sector without contractual maturity (Figure 7). On the other hand, the prevalence of overnight deposits on transaction accounts exposes domestic banks to interest rate risk that greatly depends on client behaviour. Due to their relatively high stability, banks often observe such sources as long-term liabilities, even though clients may, at any time, withdraw their funds. Therefore, banks have a relatively significant duration gap (maturity gap) between their assets and liabilities, making them sensitive to the repricing risk stemming from different moments of interest rate change for instruments on both sides of the balance sheet (Figure 8). However, amid pressures on sources of financing and increasing competitiveness, the outflow of funds from overnight deposits to time deposits could further increase financing costs and have an unfavourable effect on profit. In addition, in the medium and long term, the increase in interest rates can lead to a slowdown in lending activity, asset quality deterioration and, consequently, decline in income for banks, which may further reduce profit.

Figure 7 Deposits of the private non-financial sector dominate the structure of liabilities

Source: CNB.

Figure 8 Large share of long-term assets financed by short-term deposits without contractual maturity

Source: CNB.

2 Potential risk materialisation triggers

The slowdown in the European and the domestic economy remains the main source of the possible materialisation of risk to the stability of the domestic financial sector. Downside risks to economic growth stem from the relatively weak external environment, the prolonged duration of the war in Ukraine and continued geopolitical tensions. Current high-frequency indicators such as the PMI suggest that, in addition to the slower activity in the industrial sector since mid-2022, the services sector has also slowed down in the euro area since the third quarter of 2023 (Figure 9). The deteriorated economic outlook could have an unfavourable effect on the quality and valuation of assets on the financial markets. In addition, the turmoil on the Chinese real estate market could further decelerate the global economy, to which their main trading partners such as Germany and the US are most exposed. Recent developments on international financial markets point to high sensitivity to the trends in the Chinese economy, which could spill over to EU markets, including Croatia. Finally, the accumulated effects of monetary policy tightening could slow down economic activity somewhat more strongly than currently expected.

Figure 9 PMI for the euro area strengthens downside risks to growth

Sources: Bloomberg and S&P Global.

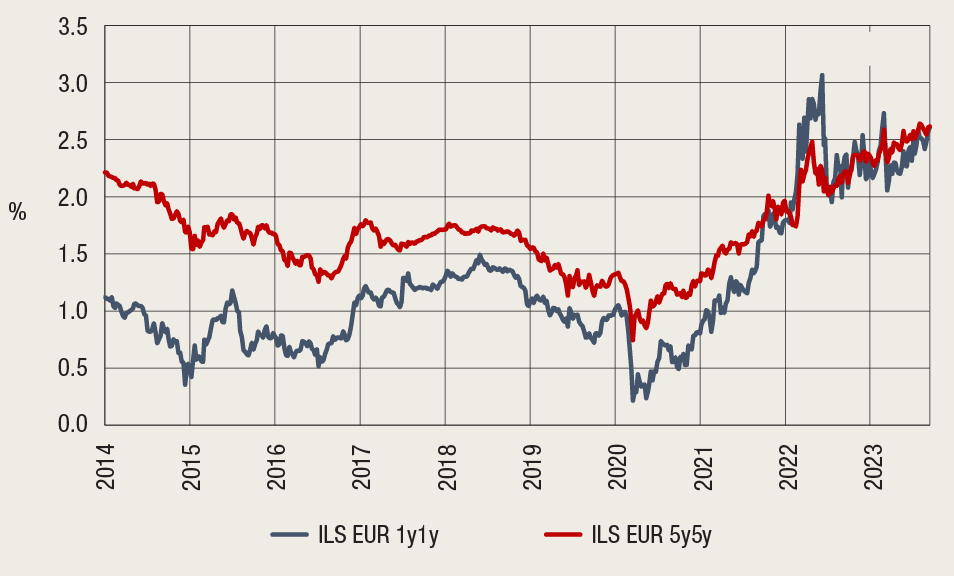

Uncertainty regarding the future path of monetary policy remains an important source of risk. If inflationary pressures turn out to be more persistent (Figure 10), central banks in major global economies could tighten monetary policy to an extent larger than currently expected or at least maintain interest rates in restrictive territory for longer than anticipated at present. In contrast, a potential premature lowering of key interest rates increases the risk of protracted high inflation and de-anchoring of inflationary expectations, which could, in turn, require an even more aggressive tightening, having an even more unfavourable effect on financing conditions and real activity.

Risks connected with the supply and prices of energy could, over the upcoming months, hamper the efforts of central banks to curb inflation. Although the storages of natural gas across Europe are almost full, the demand in winter will depend on weather conditions, while the supply and prices still have not stabilised. In addition to utilising the established routes used to deliver gas by the main pipelines from Russia, Norway, Algeria, Azerbaijan and other countries, to reduce its dependence on Russian gas, Europe is competing in the global markets of LNG. Since Saudi Arabia has signalled that it might further cut its output if the global demand for oil remains weak, oil prices have already gone up considerably. Furthermore, Russia prohibited the export of diesel and petrol, reinforcing the effect of pricier oil as a source of additional inflationary pressures.

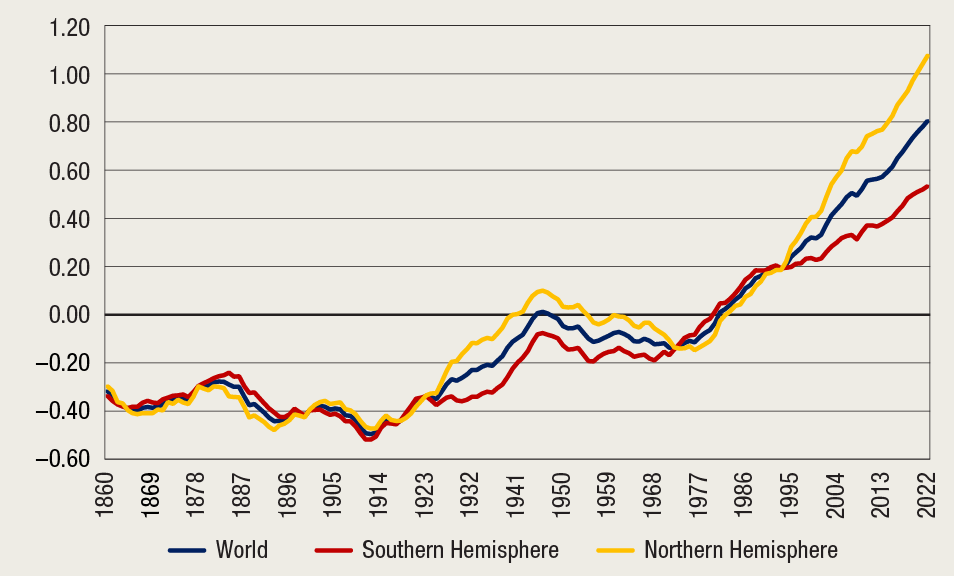

Prices of food raw materials are susceptible to risks due to unfavourable weather conditions – droughts on the Western hemisphere and the El Niño, which increase the probability of extreme weather conditions. In the case of increased prices of food and possible problems in supply, geopolitical uncertainties could strengthen further and have an unfavourable effect on global activity and trade. Factors related to climate change (Figure 11), unfavourable weather conditions and risks associated with the transition to low-carbon economy could affect the prices of certain raw materials.

Figure 10 Long-term inflationary expectations entrenched at elevated levels

Notes: 5y5y ILS (inflation-linked swap rate) measures the expected (average) inflation rate during a five-year period beginning five years from now. Short-term expectations are measured by applying a one-year inflation-linked swap rate (1y1y ILS).

Source: Refintiv.

Figure 11 Average temperature anomaly is continuously increasing

Notes: Deviation of average temperature relative to the average temperature in the period from 1961 to 1990. To reduce seasonality, the average deviation over the last ten years is observed.

Source: Met Office Hadley Center (HadCRUT5).

3 Recent macroprudential activities

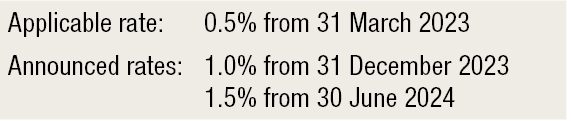

In mid-2023, the financial cycle was in a mature phase characterised by an elevated level of systemic risk. The tightening of financing conditions and the slowdown in lending were the first signs of a possible reversal. Against such a backdrop, the CNB decided to maintain the countercyclical capital buffer rate at a previously announced level of 1.5% to preserve the resilience of the banking sector in case of possible risk materialisation. The CNB performed a regular periodical review of the exposures of the domestic banking system to member states that adopted national macroprudential measures whose reciprocation was recommended by the European Systemic Risk Board, which showed that the exposures remained very low and do not require action by the CNB. Although the financial cycle in most EU member states is contracting, some countries additionally tightened their macroprudential measures aimed at mitigating cyclical systemic risks and risks associated with the real estate market.

3.1 Announced countercyclical capital buffer rate to remain at 1.5%

The regular quarterly assessment of cyclical systemic risks has shown that, at the moment, there is no need to change the announced countercyclical capital buffer rate of 1.5%. The analysis suggests that the Croatian economy is currently in a mature phase of the financial cycle characterised by elevated cyclical vulnerabilities, mainly driven by developments in the residential real estate market and strong bank lending to the private sector, showing the first signs of a possible slowdown (see chapter 1). Considering the elevated level of risk and the banks’ strong capital position and high profitability, the CNB assessed that the currently announced countercyclical capital buffer rate of 1.5%, which is to apply as of 30 June 2024, is still adequate.

Table 1 Countercyclical buffer rates

Source: CNB.

3.2 Review of exposure of domestic credit institutions to member states whose macroprudential measures were recommended for reciprocation by the ESRB

Based on the regular annual analysis of foreign exposures of the Croatian banking sector, it has been concluded that there is no need for the CNB to reciprocate macroprudential measures of other EU member states. Specifically, the ESRB recommended reciprocation, at European level, of national macroprudential measures adopted by macroprudential authorities of other EU member states[3] if the amount of exposures of domestic financial institutions exceeds the defined materiality threshold. Reciprocation is not performed automatically in Croatia; rather, the CNB verifies, for each macroprudential measure recommended for reciprocation, the amount of related exposures of domestic credit institutions relative to the recommended materiality threshold, and, on that basis, adopts a decision on the reciprocation of the measure, which is periodically reviewed.[4]

The reciprocation of national macroprudential measures was requested by the authorities of Sweden, Luxembourg, Norway, Belgium, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Germany. In line with the recommendation of the ESRB regarding the application of the principle of reciprocity, the CNB did not prescribe reciprocation, as the related exposures of credit institutions in Croatia were significantly below the recommended threshold. Upon the review performed, the CNB established that, over the past year, exposures increased slightly, but remained very low, below the recommended materiality thresholds for each of the measures. Therefore, it was decided that there was no need for the reciprocation of any of the aforementioned measures.

3.3 Implementation of macroprudential policy in other European Economic Area countries

In the third quarter of 2023, most EEA countries kept the macroprudential measures already in force, while some tightened the measures targeting cyclical systemic risks and risks associated with the real estate market. In June 2023, Cyprus raised the countercyclical capital buffer rate from 0.5% to 1%, effective as of June 2024. Norway extended the application of the national measure relating to the systemic risk buffer rate of 4.5% for all exposures in Norway and the floors for average risk weights applied to exposures secured by commercial (35%) and residential (29%) real estate in Norway by banks using the internal ratings-based approach (IRB approach) in calculating capital requirements for credit risk.

In late September 2023, Sweden introduced a minimum average risk weight for bank exposures to non-financial corporations secured by real estate in the amount of 35% and 25% for commercial and residential real estate in Sweden, respectively, for all banks applying the IRB approach. The measure was adopted to replace the previously applicable Pillar 2 supervisory measure which covered the same risks, as it was estimated that the risks in question are systemic risks to financial stability, making a macroprudential measure more adequate.

Belgium revised the combined capital buffer structure. In October 2023 it reactivated the countercyclical buffer, which was released in the spring of 2020 following the outbreak of the pandemic, with announced rates of 0.5%, to be applied as of April 2024, and of 1%, effective as of October 2024. A term shorter than the usual 12 months for the first buffer rate increase has been justified by the extraordinary circumstances in the form of increased uncertainty following a surprisingly strong interest rate increase. At the same time, Belgium decided to lower the sectoral systemic risk buffer rate for exposures secured by real estate from the currently applied 9% to 6%, applicable as of 1 April 2024. The announced rate decrease was justified by the high level of compliance of new mortgage loans with supervisory expectations and the concurrent downturn in the real estate cycle.

Table 2 Overview of macroprudential measures applied by EEA countries and the United Kingdom

Table 3 Implementation of macroprudential policy and overview of macroprudential measures in Croatia

-

Overview of the CNB’s autumn macroeconomic projections for Croatia – September 2023 ↑

-

The depositing of excess liquidity with the central bank became one of the most significant sources of increase in profitability of the Croatian banking system, with the contribution to income having reached EUR 330m in the first nine months. ↑

-

Based on ESRB Recommendation (ESRB/2015/2) whose provisions was transposed by the CNB in the Decision on the reciprocity of macroprudential policy measures adopted by relevant authorities of other European Union Member States and assessment of cross-border effects of macroprudential policy measures. ↑

-

Such an approach is in line with the practice of the majority of other EU member states and complies with ESRB Recommendation (2015/2) provided that, once a year, exposures to other countries are reviewed and that relevant measures are reciprocated where the recommended materiality threshold is exceeded. ↑